Illegal commuter taxis

Taking the risk

Mushika-shika means “quick-go”. Most vehicles used are old beaten-up and discarded cars shipped mainly from Japan. They emit dirty fumes and are often in poor technical conditions.

Worsening inflation makes the alternative taxis a massive job opportunity for thousands of chronically jobless youths who act as drivers, mechanics, cashiers – and thousands of the urban poor desperate for affordable transport.

Mushika-shikas were banned in Zimbabwe, because they are un-roadworthy and breaking every road traffic rule. Anyway, they continue to operate. In Harare, millions of urban working-class people cannot be absorbed in existing public transport infrastructure. On a typical working day, between 7 am and 4 pm, thousands of workers squeeze into bus terminals for a few state-owned urban commuter buses. In these humiliating queues, sometimes women are even molested in the scramble for scarce bus seats.

Seeing a money-making opportunity, the mushika-shikas sneak up and down Zimbabwe’s city highways, playing cat and mouse with police, whisking commuters for just 30 cents. Their attractiveness, apart from ultra-low prices, is their ability to quickly manoeuvre in the thinnest of city alleyways and ferry thousands of the urban poor to their workplaces quickly.

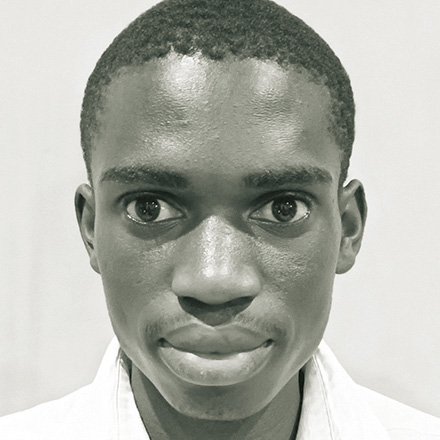

28-year-old Tonderai Gato, works on such a commuter vehicle as a conductor. However, his role goes beyond loading passengers. He sometimes acts as the mechanic to repair the vehicle when it breaks down, what could happen to the car at any time. “My job is letting the taxi drive on with doors open, my body outside in the air, the car speeding at 40 miles an hour so that passengers fit comfortably inside the car,” he says.

For Tonderai, his ‘quick-go’ vehicle means everything. “My family hospital bills, meals, children school fees depend on the earnings. I am willing to absorb the risk,” he says.

“Designed to carry a maximum of four passengers, mushika-shika squeeze a mind-boggling 12 passengers into each sedan. The drivers often drink on job and the cars hardly bear passenger injury insurance,” says Zano Sikhosana, a trade unionist in the capital Harare. Zimbabwe police have their hands full trying to waylay the illegal taxis, but the task is huge as a flood of these sedans dominates the streets.

A World Health Organization (WHO) report says that Zimbabwe’s roads are the deadliest in the southern Africa region with an average of 665 people killed each year in road fatalities. The mushika-shikas are a contributing factor. “It’s a choice between a fire and hot pan,” says Gladys Wemba, a hairdresser in Mutare. “Choose the $ 20 cents mushika-shikas and probably get your legs broken by squeezing or accident or take a safer state bus; arrive an hour late at work and get fired.”

Progress Mwareya is a freelance journalist based in east Zimbabwe.

progressmwareya2@gmail.com