Governance

Lessons on democracy from South Africa and Ethiopia

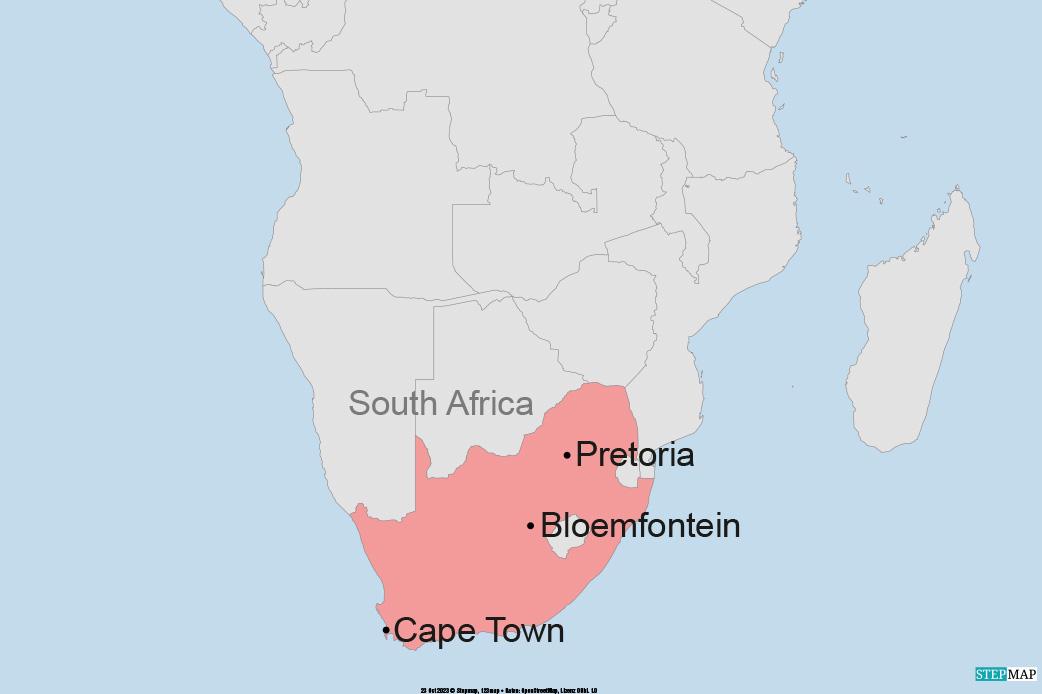

South Africa’s transition from apartheid in 1994 led to the establishment of one of Africa’s most stable constitutional democracies, based on freedom of the press, independence of the judiciary and regular elections. Three decades later, however, democracy is under considerable pressure. The 2024 elections marked a turning point, as the African National Congress (ANC) suffered its worst election defeat and failed to win a parliamentary majority for the first time since 1994. This change reflects the population’s growing frustration with corruption scandals, economic stagnation and governance failures.

The rise of populist movements, particularly the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and former President Jacob Zuma’s uMkhonto weSizwe Party (MK), has exacerbated political divisions. These parties exploit economic inequalities and historical grievances, making consensus-oriented governance increasingly difficult. Fuelled by corruption and mismanagement, the loss of public trust in institutions further threatens democratic stability. Despite these challenges, South Africa still has institutional safeguards in place, such as an independent judiciary and an active civil society, which can help overcome the democratic crisis if political leaders prioritise reform and accountability.

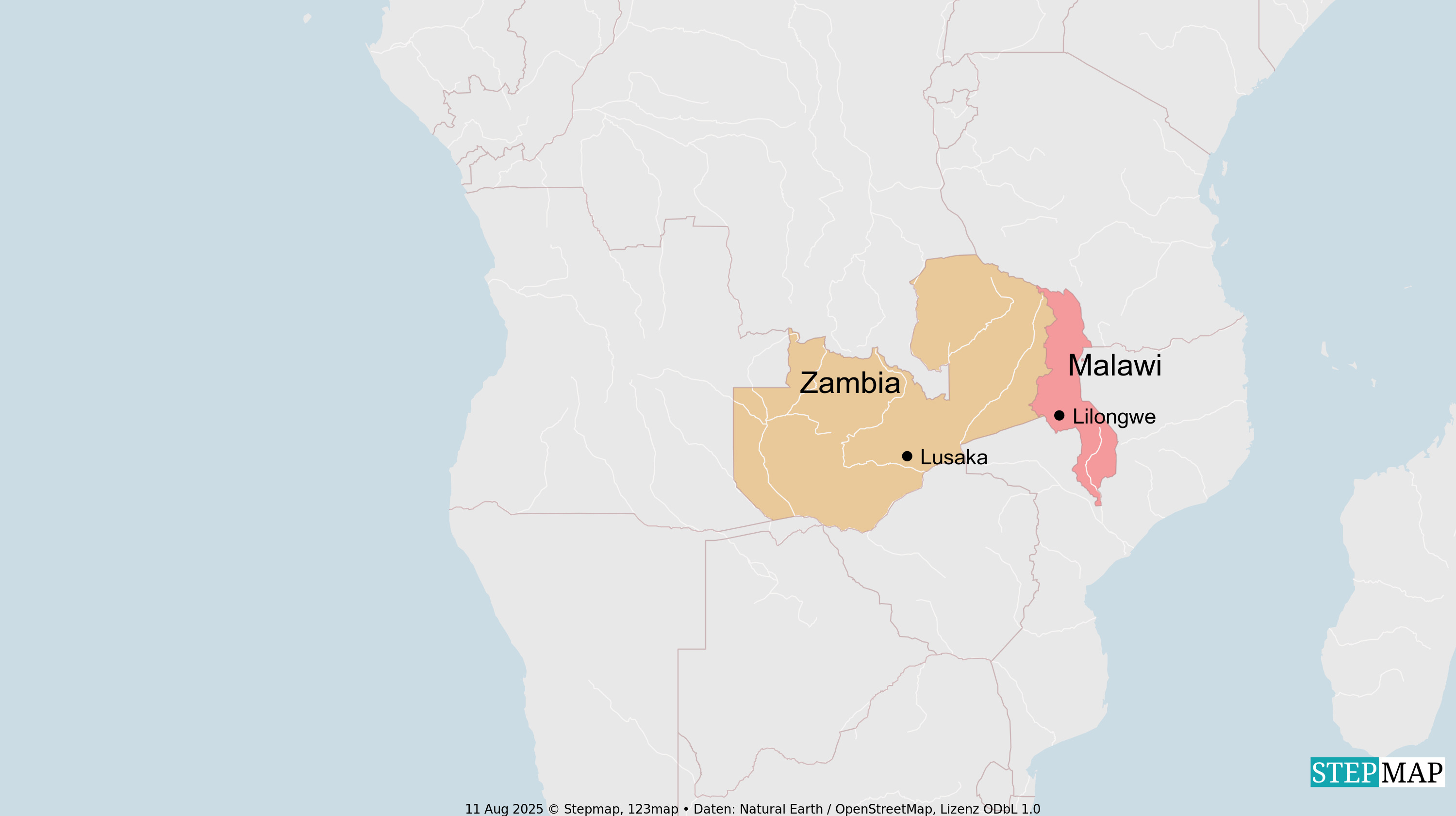

Ethiopia’s democratic course has also become significantly less stable. The rise of Abiy Ahmed to prime minister in 2018 and his winning of the Nobel Peace Prize, especially for his policy of reconciliation with neighbouring Eritrea a year later, initially signalled a break with the country’s authoritarian past and promised political liberalisation. However, this optimism quickly faded as his government reverted to repression, censorship and centralised control.

The 2021 elections, which were marred by voter suppression and widespread conflict, underscored Ethiopia’s regression in terms of democracy. Parts of the population were excluded from the electoral process and key opposition leaders were arrested, meaning that the elections were neither free nor fair.

Furthermore, Ethiopia’s ethnic federalist system, which was originally intended to decentralise power, has in fact exacerbated ethnic divisions and instability and sparked violent conflicts. Ethiopia introduced ethnic federalism and restructured the country’s regions along ethnic lines after the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) took power and overthrew the military junta in 1991.

Insights for Africa’s democratic future

The experiences of South Africa and Ethiopia provide important insights for democratic governance across Africa.

Firstly, institutions alone are not enough. Political will and civic engagement are essential for sustaining democracy. South Africa’s independent judiciary and free press remain intact, but increasing polarisation will weaken them too unless proactive reforms are forthcoming. In Ethiopia, weak institutions have enabled authoritarian consolidation that leaves little room for democratic debate.

Secondly, elections do not guarantee democracy. The electoral process in Ethiopia makes it clear that elections without transparency and political competition are more symbolic than substantive. Even in South Africa, declining voter confidence signals that procedural democracy is not enough – politicians must be accountable and responsive to the concerns of the public.

Thirdly, political polarisation and ethnic divisions are existential threats to democracy. Populist rhetoric in South Africa risks undermining democratic norms, while Ethiopia’s ethnically based federalism has exacerbated conflicts rather than promoting integration. In both cases, inclusive governance and efforts to overcome social divisions are crucial.

Africa’s democratic future depends on the resilience of its institutions and the commitment of its leaders and citizens to upholding democratic principles. South Africa still has the institutional framework to overcome the current crisis, provided it implements reforms to restore public confidence and curb corruption. Ethiopia, on the other hand, needs fundamental political restructuring to prevent further erosion of democracy and instability.

Democracy is not a sure-fire success; it requires vigilance, reforms and the active participation of citizens. The experiences of South Africa and Ethiopia show that democratic progress is possible, but fragile. If Africa’s democracies are to survive, they must not only defend their institutions, but also create a political environment in which inclusion, accountability and the rule of law take centre stage.

Hafte Gebreselassie Gebrihet is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance, University of Cape Town (UCT). His research focuses on building democratic governance and resilient institutions in Africa with particular emphasis on the UN Agenda 2030 and the Africa Agenda 2063.

hafte.gebrihet@uct.ac.za