Cadre organisation

Taken by surprise

The Muslim Brotherhood (MB) neither started nor led Egypt’s revolution. Its leadership does not even share most of the revolutionaries’ aspirations for freedom, radical democracy and re-distributive policies. As the only well-organised political force in the country, the MB nonetheless benefited from the power vacuum created by the ouster of the Mubarak regime when the popular uprising proved unable to translate its vision into a coherent political strategy.

The MB only joined the revolution once it was clear that this movement was more than a passing outbreak of popular anger. In the meantime, the MB has gradually crafted a power sharing deal with the military, which took power in February 2011. The details of this deal were worked out gradually and included a series of limited power struggles. Both parties had an interest in limiting the effects of the revolution. The military supported the MB's access to power in exchange for the protection of their economic and other interests.

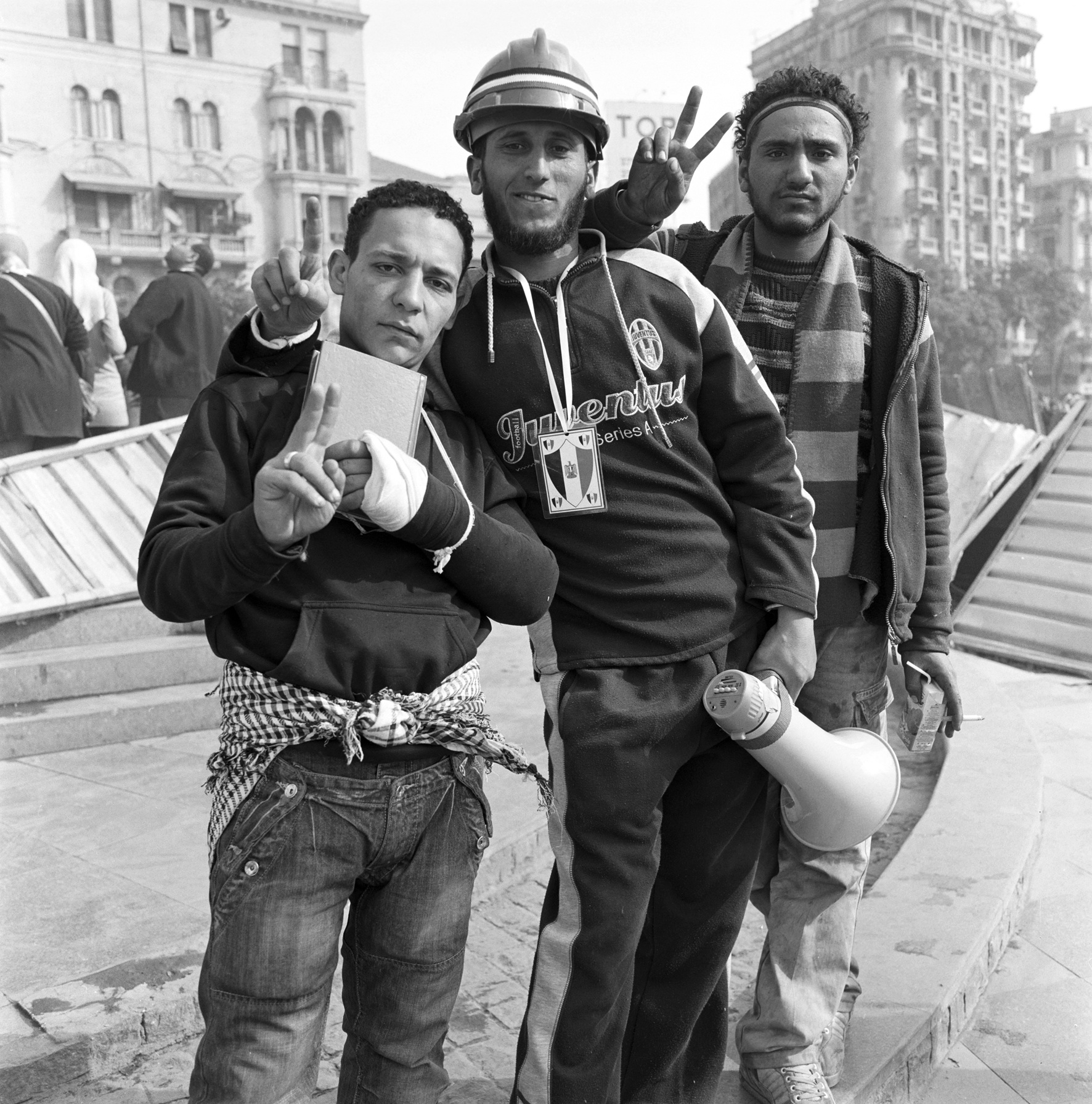

The success of the MB and other Islamist forces was neither a natural nor an automatic outcome of the revolution. Up to 8 million Egyptians had actively participated in the mass demonstrations, strikes and the occupation of public spaces. Various Gallup polls showed that eight out of 10 Egyptians supported the revolution in 2011. The revolutionary goals are quite different from the Islamist agenda the MB is trying to impose today in cooperation with other Islamist forces.

Recent events show that the revolutionary spirit is still capable of mobilising people in the big cities, provincial towns and even parts of the countryside. Indeed, it seems that the MB is in office, but not fully in charge. Its popular support is waning – half of its voters in the parliamentary elections in 2012 did not vote for the MB presidential candidate only a few months later.

The revolution took the MB by surprise. It suddenly faced the double challenge of having to compete with other political forces and, at the same time, dealing with internal conflicts that had earlier been kept in check by ideology and solidarity in view of suppression. Unlike the MB leadership, which includes many wealthy businessmen and professionals, the organisation’s rank and file is largely made up of middle-class and lower-middle-class Egyptians. Many of them appreciated the revolutionaries’ demands of freedom, transparency, social justice and participatory decision-making.

The MB leadership responded to the double challenge by forming a tactical alliance with various Salafist groups. This new political camp is trying to Islamise the revolutionary discourse and to construct the dichotomy of an Islamist “us” versus an anti-Islamic, westernised “them”.

Islamist alliance

Initially, the MB acted as the more moderate brain of this coalition, while various Salafi groups engaged in more confrontational campaigning. For instance they attacked Copts, Sufi shrines and opposition forces. Moreover, they made provocative statements demanding gender segregation, the prohibition of alcohol or veiling of pharaonic statues. In the meantime, matters have become more blurred. MB members too have been involved in bloody clashes, while the Salafist Nour party has occasionally called for more accommodation of the opposition.

The Islamist alliance agrees on a number of key issues, including:

- insisting on an Islamist constitution,

- backing President Mursi against opponents,

- opposing adverse verdicts of an increasingly politicised judiciary, and

- undermining opposition media.

Unlike the MB, the Salafis are not bound together in a hierarchical organisation. They are loosely grouped around charismatic sheikhs and leaders of formerly militant jihadists. The non-militant Salafis have traditionally preferred to stay out of politics in order not to corrupt their purist understanding of Islam. The newly formed Salafi parties are manoeuvring between purist ideology, militant attitudes and the pragmatic challenges of politics.

The result is a double-edged discourse targeting the general public on the one hand and the highly ideological base on the other hand. The obvious results are incoherence and frictions. At the same time, tensions with the MB are growing because the MB has backtracked on power sharing promises and is promoting its own members to leadership positions in state institutions. Indeed, most Egyptians would probably agree that reform under the Mursi government has been largely limited to a “Brotherhoodisation” of the state. This has recently led to an unprecedented stand-off between the MB and Nour on the matter.

The MB approach to politics is rooted in the organisation’s very nature. It is a secretive cadre organisation based on hierarchy and discipline (see box).

Policymaking

In April 2012, the MB announced its development project for Egypt's future under the ambitious headline “Nahda” (Renaissance). The 11-page document talks about reducing the size of the state and a greater role for the private sector and civil society. It promises to double domestic production in five years, eradicate illiteracy, reform the education system and restructure the security apparatus. It wants to up-grade the military and “restore” Egypt’s international role.

The document is vague, however, and does not spell out how the goals are to be achieved. There is no strategy on social justice, a core demand of the revolution. Poverty is only indirectly referred to within the charitable context of a “revival” of the Islamic institutions of “waqf” (religious endowments) and “zakat” (compulsory donations for charity).

So far, Mursi’s government and MB-dominated legislative bodies have done little to strengthen either the economy or civil society. Consumer prices are rising and the government’s financial difficulties are becoming ever more evident. The government is obviously confused and overburdened. It recently cancelled some unpopular measures relating to subsidies and taxes only a few hours after they had been decreed.

Corruption has not disappeared. The media is full of news and rumours of MB businessmen taking over businesses of their competitors, demanding commissions for facilitating business opportunities and making deals with representatives of the old regime.

President Mursi granted himself almost absolute powers in a constitutional declaration in November 2012. Ever since, protests have become increasingly violent. In spite of huge demonstrations, the MB pushed through a new constitution in the constituent assembly after most non-Islamist members had withdrawn. It gives the president the right to appoint the governors and the heads of almost every independent authority in Egypt, including the central bank. New rules and draft laws on NGO and trade-union activities, demonstrations and the media focus on control and constraint rather than rights and freedoms.

There is no effective formal opposition in Egypt today. Street protests, strikes and violence are becoming ever more common. Protesters have attacked MB offices across the country, demanding the “downfall of the rule of the murshid”. The “murshid” is the MB supreme guide. On the other hand, security forces and MB members attack activists and journalists, both physically and with legal action. They went as far as kidnapping and torturing activists and journalists in mosques in December 2012 and again in March 2013.

Foreign affairs

On the foreign-policy front, the MB has managed to enlist the support of the US by indicating that it is prepared to drop its former hostility towards Israel and respect US interests in the region. It continues to pursue the same neoliberal policies as the old regime did. In regard to the peace treaty with Israel, an FJP (Freedom & Justice Party) leader said that the FJP/MB would “respect international obligations, period”. The Israeli newspaper Haaretz praised “the current security coordination between Israel and Egypt” last summer.

Egypt has pressured Hamas to accept certain Israeli conditions in the Gaza truce agreement and beyond, and agreed to maintain “strategic ties” with Washington, give the US access to its airspace and bring in American troops and sophisticated surveillance equipment into Sinai's demilitarised Area C. For the US, an MB controlled government may prove an even more effective partner than the old regime was. With electoral legitimacy and Islamic authenticity, it may be better positioned to exert influence on Hamas and other Islamist forces in the region.

In exchange, the US seems to abstain from exerting too much pressure with regard to democratic governance, human rights and freedoms. US officials have focused more on convincing the opposition to accept compromise than on insisting on the rule of law. The US continues to support Egypt with aid and military equipment, and it has promised to help Egypt to get funding from the IMF.

Qatar has become another strong supporter of MB dominated Egypt, while Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates remain rather sceptical. Their position dates back to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990, when the MB opposed US intervention to liberate Kuwait.

Qatar, however, hopes to bolster its political and economic clout in the region by supporting Islamist groups in Libya, Syria and Tunisia, paying particularly favourable attention to MB-affiliated groups. In Egypt, Qatar is looking for strategic investment opportunities. It also wants to enlist Egypt’s support for Qatari candidates for leadership positions in regional and international organisations. Doha granted Egypt $ 5 billion worth of deposits at the central bank to boost its foreign currency reserves. Al Jazeera is now clearly supporting the MB. The Egyptian opposition, however, is highly critical of Qatar’s growing influence.

Outlook

So far, the MB does not seem up to much more than replacing the old regime with a new elite, set to exploit the country’s resources and suppress its people. The big question is whether it will succeed. That will require an unprecedented level of repression. The revolution has toppled an authoritarian regime, and the people have not bowed to intimidation and repression since.

The MB probably never intended to enter into a cycle of violence, hoping for a more hegemonic role. However, in view of stronger opposition than anticipated, the MB leadership obviously decided to seize the moment and grab whatever power it can. The government currently seems to rely more on the explicit, implicit or tacit support of the US, Qatar and the Egyptian army than on Egypt’s people.

Its rule is anything but firmly established. The MB is challenged by street protests, vibrant opposition media and the “deep state”. The deep state consists of a defiant bureaucracy as well as security and judicial apparatus which all have their own interests and were set up during the Mubarak regime.

While the government’s pragmatic stance on economic and foreign-policy issues does not fit the MB’s ideological rhetoric, its radicalism is contributing to increasing violence. This trend may prove difficult to reverse should the MB take a more conciliatory approach one day.

Egyptians are known to be rather religious people, but the traditional notion of religion emphasises life, tolerance, spirituality and human values. The people are exhausted by poverty and certainly don’t want religious leaders to interfere in their private lives. Many are beginning to feel that they must protect their traditional understanding of religion against those they call the “traders of religion”. The MB-led Islamist experiment in Egypt may thus eventually bring Egypt much closer to a truly secular state than ever before.

Muna El Shorbagi lives in Cairo and is currently working on her PhD thesis on how radical Islamist concepts related to the perception of the “self” and the “other” resonate with various social strata.

m.shorbagi@gmail.com