Indigenous peoples

Fighting “green colonialism”

How do you define climate justice?

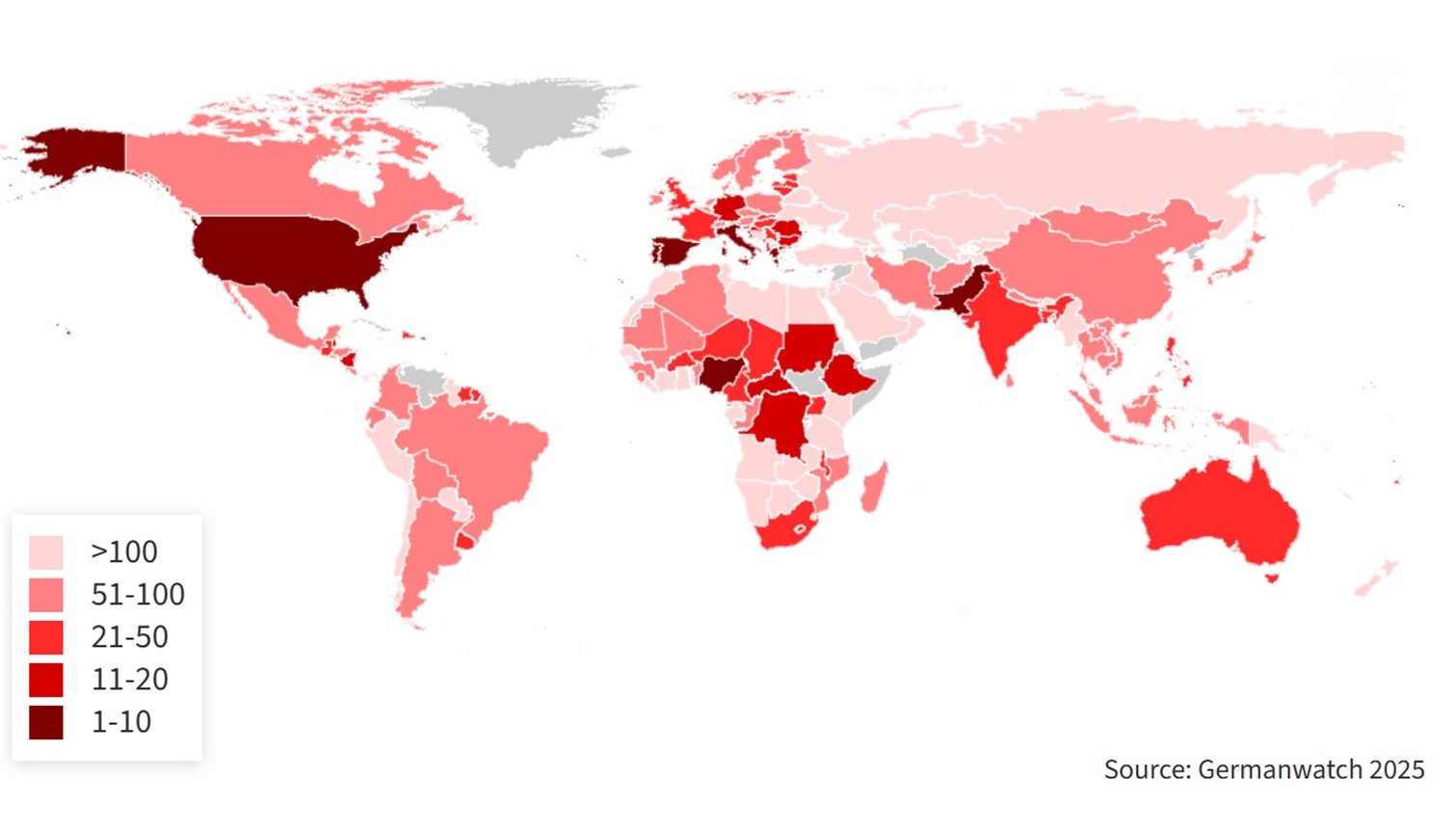

It means that those that have caused the crisis are accountable for it. They have the responsibility to address the situation and assist those who are suffering disproportionately because of the impacts. Climate change is a result of industrialisation, so high-income countries with long industrial histories must assume responsibility. Poor countries lack the means to cope with global environmental change, so they deserve support. Rich nations, however, must not only support poorer ones, they also need to drastically reduce their carbon emissions. Currently, they are not changing their unsustainable lifestyles and exploitative economic system as they should.

What is the perspective of indigenous peoples?

We indigenous peoples have the smallest carbon footprints. We live in areas where the impacts of global warming are felt, but we do not have the means to cope with the rapid changes that are happening. In the past, we could adapt because things happened slowly. Now change has become fast, drastic and largely unpredictable.

To what extent are your voices heard in global debate?

We are making ourselves heard in climate talks but our rights and well-being are not fully addressed. We can make significant contributions, especially in regard to our knowledge and practices of sustainability. How we think about resources matters. We consider them valuable not only because they serve our present needs, but just as much because future generations will need them too. Therefore, we manage – and conserve – them diligently. Accordingly, a large share of the Earth’s remaining biodiversity is found on indigenous peoples’ territories. Indigenous communities focus on the common good, not individual interests.

Do you want that to be the international approach too?

Well, the global pattern is to look at resources from a commercial perspective, focusing on the monetary and commercial value. The profit-maximising extractivism is what has caused climate change. Businesses thrive on creating a lot of artificial demand so people will consume more. Production and consumption thus result from profit interests. Sustainability and social equity are not prioritised. This mindset needs to change.

Do you think that will happen?

Yes, I see mindsets changing, especially among young people. There is a trend of people reducing consumption to reduce their carbon footprint. They are also in the streets and taking action demanding governments to take drastic actions to save their future. Many people pay attention to recycling, moreover, buying second-hand clothes instead of new ones, for example. There is also a spirit of volunteering. People clean up, collect garbage and don’t create more waste. Small changes matter. The more people join in, the more we will achieve. Nonetheless, we must still address the root causes. Those that have caused the crisis need to change their behaviour immediately. Systemic changes at a global scale to change the extractivist and unsustainable economic system must be implemented.

Were you happy with the results of the climate summit in Egypt last year?

It is a big step forward that a loss and damage mechanism will be established. I see it as a crucial accountability mechanism. From the perspective of indigenous peoples, loss and damage means renewing our harmonious relationship with nature. It is important to rehabilitate areas that were destroyed and degraded, and it requires funding and technical support. Direct, appropriate and adequate support and assistance to indigenous communities suffering from the impacts of climate change such as flooding and drought should also be provided. We need to ensure that the environmental destruction will not happen again.

What dangers are looming on the way to a sustainable world?

A just transition is an important part of climate justice. We support the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy, but it must not harm indigenous communities. Unfortunately, that is what is happening. Our land is being grabbed for renewable energy projects – whether for windmills, solar farms or dams. The extraction of transition minerals without the consent of indigenous peoples, without equity and the protection of the environment is green colonialism in the name of climate action. We need to make sure that human rights are upheld and principles of social justice are applied in the course of the transition. Far too often, we indigenous peoples are not considered. Our resources are exploited without our free, prior and informed consent which is part of our fundamental right. Once again, we are on the losing end. We are being sacrificed, even though we are doing the most to protect the global environment.

What is your organisation, Indigenous Peoples Rights International (IPRI), doing?

We are raising awareness, supporting communities defending their lands, territories and resources and advancing policy reforms for the respect and protection of indigenous peoples’ rights against criminalisation and human-rights violations with impunity. We insist on solutions that respect rights and facilitate inclusion. When decisions are made without us, no one understands the impacts of climate change and so-called development on our lives. We are doing what we can to make ourselves heard. We are not simply victims, we insist on our rights and we provide solutions.

Do you see racism in how the climate crisis is being addressed?

Yes, there is a strong racist undercurrent. Some people are privileged and others are denied their rights and a life in dignity. “Why would we change our economic system and comfortable lifestyles?” is a racist attitude when the poor people, the majority of which are the “coloured people” are suffering because of these. It flies in the face of the need for global solidarity to drastically reduce carbon emission at its source and assist those that are suffering from the impacts of climate change but have contributed the least.

In 2018, you were labelled a terrorist by the administration of Rodrigo Duterte, who was the president of the Philippines. How did that change your life?

I fully understand what human-rights defenders at risk are facing. It really affects you emotionally and mentally. It causes a lot of uncertainty, stress and anxiety. It becomes hard to focus on the work you want to do. Sometimes it makes it very difficult to pursue different advocacy strategies because of the risk and possible consequences to the life and well-being of activists in the front line.

Did you begin to doubt your mission?

No, I did not. Indeed, the government’s approach strengthened my belief that we must not consider this kind of authoritarian governance normal. We need change. Trampling on human rights is plainly unacceptable. What I found encouraging, was the strong expression of solidarity at the local, national and international level. It was quite overwhelming, and ultimately made the administration drop the charges, not only against me, but other activists as well. At that time, UNEP, the UN Environment Programme, gave me the Champions of the Earth award. More generally speaking, environmental activists and human-rights defenders deserve to be honoured. We are not terrorists and should not be forced to live in fear. We are promoting the common good, not special interests.

Does the IPRI have more encouraging news from other countries?

Yes, recent developments in Brazil and Colombia are quite encouraging. People who are partners of IPRI have recently risen to powerful positions. Sônia Guajajara is now Brazil’s federal minister for indigenous peoples, and Leonor Zalabata Torres is now Colombia’s new permanent representative to the UN in New York. She is a member of our board. These two strong women will hopefully be able to make invaluable contributions to advance the protection of our rights, well-being and aspirations not only in their respective countries but globally as well.

How do you assess climate justice in middle- and low-income countries?

I see more and more social movements rising up in these countries. On the other hand, there are more authoritarian governments. Political repression is a huge challenge. We face increasing risks when we speak out. In most places, the approach to development is still unsustainable. The only good thing is that Jair Bolsonaro was not reelected in Brazil. However, he still has many supporters and there is a right-wing movement. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva attending the climate summit in Egypt, however, was a breath of fresh air. We as indigenous people met with him there and appreciated his clear commitment to protecting the Amazon.

How do you assess the situation in China?

China is a very complex country. What is clear is that China is aspiring dominance, which is why they are offering huge investments and funding. They are literally all over Asia, Africa and Latin America with investments. China does not have effective accountability mechanisms, and they have a permanent seat in the UN Security Council. The People’s Republic of China is positioning itself as an economic power, but with no environmental or social safeguards including respecting and protecting human rights.

Do you see any positive impulses coming from China in terms of climate issues?

At the domestic level, I think they are trying to rise to the challenges. That is a good thing for the Chinese people. They focus on gaining economic control globally but not on achieving sustainability and social equity. They need to acknowledge that we share the world’s resources and we must collectively manage them sustainably to the benefit of all of humanity. That is what global solidarity is about. We will all be doomed if every country – not only China – does what it can to protect its own people to the detriment of others.

Joan Carling is an indigenous rights and environmental activist. She is the executive director of Indigenous Peoples Rights International (IPRI), a non-profit organisation defending the rights of indigenous peoples. In 2018, Joan Carling was awarded the Champions of the Earth award by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

euz.editor@dandc.eu

Twitter: @JoanCarling