Stand point

Mechanisms of oppression

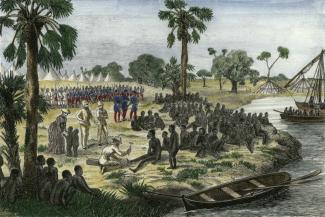

At the time, I was doing research for my PhD thesis, and the longer I worked on it, the more I came to understand that the difference between the museums actually stood for the difference between the two states concerned. The United Kingdom had modernised and become more inclusive. Progress was apparently much slower in India. Many colonial conventions were still in force, officialdom still used English and masses of people still lived on the margins of society. I am not saying that British colonialism was a blessing. No doubt, it was an oppressive, exploitative system. The depressing truth, however, is that its way of depriving masses of basic rights and freedoms proved so strong and so deeply rooted that it still has not been overcome even today, seven decades after India became independent.

Things tend to be similar in many former colonies. Liberation movements won, but all too often they only replaced the alien elite with a new domestic one. It felt – and still feels – comfortable lying in the former masters’ beds, as I recently heard Job Shipululo Amupanda, a young Namibian scholar put it.

The notion of human rights was born in Europe’s Enlightenment. These rights are cornerstones of the UN system and have inspired the Sustainable Development Goals. The basic idea is that every person is of equal value and entitled to self-determination. It is an unsettling historical truth, however, that European Enlightenment also went along with colonialism and slavery. Neither is acceptable anymore, of course.

After the colonies gained sovereignty, the former colonial powers soon cast themselves in the new role of benevolent donors, and a few decades later, they felt entitled to giving lectures on issues of governance. Western governments were keenly aware of corruption, human-rights abuses and authoritarian leanings in developing countries, all too often failing to remember that their own predecessors had laid the foundations of misrule.

The hypocrisy was obvious to people in developing countries where most people did not know from first hand experience that countries like Britain had indeed become more inclusive. To many people, the kind of strongman arrogance US President Donald Trump displays today seems to be the global norm – not the exception. After two or three generations of independence, however, it no longer makes sense to keep blaming only the former colonial powers. The current governments must be held responsible too.

Democracy cannot be imposed, but only encouraged from outside. It is up to the people of every country. Getting a grip on the historical truth is healthy. It can help to promote the cause of emancipation in a way that conditional official development assistance (ODA) cannot.

By the way, I haven’t returned to the Indian Museum for 20 years. I did recently check its website, however. That it has a website is good, but what I found on it, looked all too familiar.

Hans Dembowski is editor in chief of D+C Development and Cooperation / E+Z Entwicklung und Zusammenarbeit.

euz.editor@fs-medien.de