UN Sustainable Development Goals

The SDG’s core vision: an opportunity for development cooperation

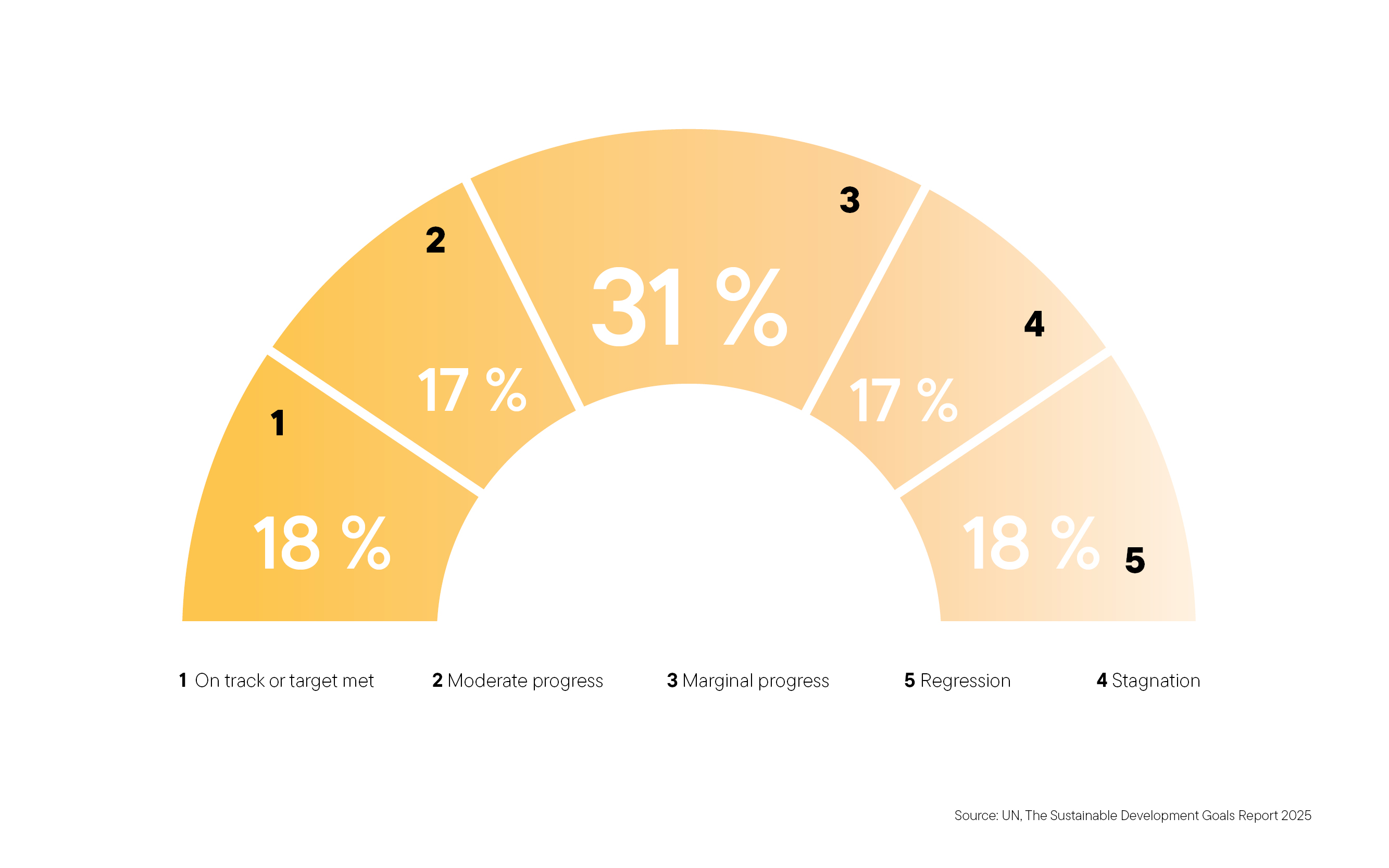

Disillusionment reigns ten years after the 2030 Agenda came into force. Not only will the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) not be reached; the currently challenging situation means that some indicators may even regress compared to their original 2015/16 level. Development cooperation finds itself in serious crisis. At the same time, it is becoming increasingly clear among private sector actors that the sustainability efforts undertaken by the business world to date will not lead to the goals being achieved either.

If progress is ever to be made, development cooperation and the private sector must return to the original idea behind sustainable development, which is to combine environmental and climate protection with development. International cooperation between actors from different sectors is vital to achieve this and offers considerable potential for development cooperation. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the area of climate action: success will only be possible if the Global North and the Global South work together. This approach is the only way to better address the unresolved issues entailed by conflicting ecological, economic and social goals – with a view to benefiting people all over the world.

The current situation

Development cooperation is going through a difficult time. Support is crumbling, especially in the US, though also in European countries. The economic recession means the willingness to invest internationally is declining in Germany, too. As a result, less funding is available. Geopolitical tensions are additionally hindering multilateralism.

Consequently, the ‘Decade of Action’ proclaimed by the United Nations has failed to materialise and the 17 SDGs laid down in the 2030 Agenda will not be reached by 2030. However, the aforementioned recent developments are not the only reason for this, as there have been obstacles from the outset. These include conflicting economic and ecological goals that have yet to be resolved, such as the importance of reconciling economic growth with the need for climate action. A lack of international cooperation and, in many cases, a primarily national approach – for example to climate action – have also hindered the process. A glance at what companies are doing in this respect and at the regulatory requirements guiding their actions speaks volumes. Gigantic funding gaps and problems with the availability and transfer of sustainable technologies make matters even worse.

Moreover, the term sustainability is widely misinterpreted: in Germany it is used far too often to refer to ecological issues. Most people did not understand why Gerd Müller, Germany’s former development minister, wanted to turn the Federal Ministry for economic cooperation and development into a “Federal Ministry for international cooperation and sustainability”. Too many people have failed and continue to fail to recognise that the 2030 Agenda is a global system of goals that requires all the goals to be achieved simultaneously.

Back to the roots: environment and development

Before attempting to answer the question of “What next?”, we should look at the original definition of sustainable development and the story behind it. This leads us to the first UN Conference on the Human Environment in 1972, where the then Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi stressed that developing countries had the right to economic development. She asserted that this right must not be sacrificed for the greater good of environmental conservation and that both goals should be pursued in parallel. This concurrency was later enshrined in the Brundtland definition: sustainable development means bringing about economic development worldwide while at the same time protecting the environment and the climate. And this is precisely what Klaus Töpfer, Germany’s former environment minister and executive director of the UN Environment Programme, dedicated his life to achieving. There is a lack of voices such as his nowadays.

The 2030 Agenda reflects this core vision, which is all too often forgotten: it aims to ensure that basic human needs are met worldwide (SDGs 1–6) – which does not mean offering yoga classes as part of corporate healthcare management schemes, as European companies like to boast about in their sustainability reports. It is also a question of creating an economic system that generates prosperity while reducing inequality (SDGs 7–12). Then there are the environmental and climate protection goals (SDGs 13–15). All of this requires strong institutions and global cooperation (SDGs 16–17).

Many actors in politics and business lack an in-depth understanding of the complex interconnections. Only those with a sense of the interplay between ecological, economic and social aspects can take action that does not ignore the fact that doing justice to the 2030 Agenda means addressing it as a global system of goals.

It is vital to formulate a positive vision of the future – in many places, such optimism appears to have been lost. The German public increasingly associates sustainability with proscriptive rules, with a loss of prosperity and with bureaucracy. What seems to have been forgotten is that the 2030 Agenda essentially entails an extremely positive promise: successfully protecting the environment and the climate will secure the wellbeing of all humankind.

Cooperation is essential

Sustainable development is a supremely global challenge that demands cooperation. There can be no sustainable Germany nor any sustainable company in an unsustainable world. Game theory expert Axel Ockenfels stresses that climate change is the “greatest cooperation problem in human history”.

Climate action can only be successful if it involves everyone, for the only relevant goal is to reach global net zero. Unilateral national approaches are not helpful and often even prove counterproductive because they weaken the trailblazer economically and, rather than eliminating emissions, simply transfer them to other countries. Leading German economic institutes pointed this out just recently. As Simon Stiell, executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, also stressed at COP30 in Belém: “Individual national commitments alone are not cutting emissions fast enough”. This should certainly resonate with Germany.

Progress will not be possible without a cooperative approach between states, businesses, civil society and consumers that also reflects the development needs of the Global South. The necessary gigantic financial burden can only be shouldered jointly. In the area of development cooperation, these interconnections offer a great opportunity to leverage climate action to address other issues too. To this end, development cooperation actors should strive for much greater interaction with the private sector.

The Paris Agreement – neglected details

The two-degree target stipulated in the Paris Agreement can only be reached if the international community of states works together. It is not surprising that global carbon emissions are continuing to rise steadily. A glance at the climate targets agreed by the signatory states reveals that the targets of industrialised and developing countries differ considerably and that industrialised countries have a dual responsibility. Absolute carbon reduction targets were set for them, whereas developing countries are obliged “merely” to improve the carbon intensity of their GDP growth. This means that their carbon emissions are even allowed to increase – albeit less sharply than GDP – if they see economic growth. This is where the maxim proclaimed by Indira Gandhi more than 50 years ago comes into play: environmental and climate protection must not hinder development.

A second fundamental difference is that most climate targets for developing countries are conditional: they must and can only be reached if substantial funding is made available by industrialised countries – according to the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities.

The industrialised countries are thus facing a double task: they must not only achieve their own targets but also support developing countries in reaching theirs. The final declaration at COP29 in Baku in 2024 noted that $ 1.3 trillion per year needs to be raised by public and private sources by 2035 in order to help developing countries reach their targets. This is a huge joint fundraising challenge that has never been even remotely achieved in the past. While Germany made nearly € 12 billion available for international climate action in 2024, Kenya alone will require € 9 billion of international support per year between 2031 and 2035 – as it states in its latest NDC (Nationally Determined Contribution) report.

The order of the day

The situation described above makes it imperative to use the limited financial resources efficiently. This must be the order of the day. For Germany and other industrialised countries, it’s not about eliminating the last tonne of carbon at home, whatever the cost. Instead, it’s about internationally deploying the funds available for climate action with maximum effectiveness, taking advantage for example of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. It permits states to cooperate internationally to jointly reduce emissions. In this way, industrialised countries will be able to reach their own climate goals more cheaply while at the same time supporting developing countries in reaching their targets.

This will also allow private actors such as companies to contribute to international climate action in ways that benefit other SDGs too. This is precisely what the Development and Climate Alliance established by Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development in 2018 advocates. It should finally receive the public recognition and clear political support that this cause deserves. The foundation supports companies, institutions and private individuals who voluntarily pursue climate action projects in countries of the Global South.

Ways to move forward

International climate funding is a lever for development and thus for the 2030 Agenda as a whole. It urgently needs to be expanded. To this end, development cooperation actors should urge Germany to live up to its dual responsibility as an industrialised country and support the achievement of the climate targets of the Global South far more comprehensively than before. In addition, cooperation with the private sector should be massively stepped up, as it must make a significant contribution to international climate funding.

Who should be campaigning most emphatically for this to happen if not the development cooperation sector? Climate change, after all, is one of the big threats that could jeopardise the development progress made so far. At the same time, it offers perhaps the greatest opportunity for much wider development cooperation: without development there can be no successful climate action – it is vital to understand and ensure broad-based acceptance of this fact in society. Anyone wishing to succeed in climate action must dedicate themselves also to development cooperation.

Estelle Herlyn is the scientific director of the Competence Centre for Sustainable Development at the FOM University of Applied Sciences for Economics and Management in Düsseldorf. She initiated the Development and Climate Alliance and works among other things as a senior advisor for UNIDO.

estelle.herlyn@fom.de