Democratic governance

A mixed bag

ECOWAS was formed as a regional economic organisation, but it became internationally best-known because of its interventions in civil wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone. How did that happen?

Yes, ECOWAS was established in 1975 with the formal aim of promoting economic cooperation among its 15 members, which shared similar socio-economic conditions. The historic trajectories of colonial rule, administrative cultures and language were different, however, so there were hiccups. The regional body was soon confronted with many political crises, ranging from civil war to various military or constitutional coups d’état. This forced ECOWAS to fully embrace the security agenda as a core business. Economic integration cannot thrive amidst instability. In 1989, ECOWAS signed a defence pact and established the regional force ECOMOG – the ECOWAS Monitoring Group – to deal with insurgencies in Liberia and Sierra Leone. The ECOMOG was instrumental in peace enforcement and peacekeeping operations in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

What were the long term impacts?

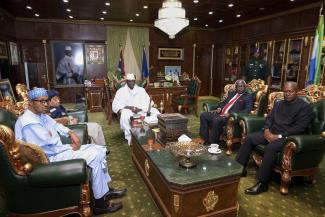

Well, the ECOMOG helped in post-conflict reconstruction, contributing to efforts for disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR). They were also active in both Guinea Bissau and the Republic of Guinea. Collective force was similarly used to restore democracy in cooperation with French troops in Mali after the military coup of 2012. Last year, Gambia’s long-serving president Yahya Jammeh finally accepted electoral defeat shortly after ECOWAS started a military intervention. In 2009, ECOWAS had threatened to use the brigade to forcibly remove from power Laurent Gbagbo, who refused to acknowledge that he had lost the presidential elections in Côte d’Ivoire in 2009. There too, French troops intervened, and ECOWAS would have supported them had Gbagbo not been apprehended fast.

Democratic norms seem to be more deeply entrenched today in West Africa than in any other African region. Why has ECOWAS been more assertive in this respect than other regional organisations in Africa?

It is true that the democratic credentials are more pronounced in West Africa than in any other part of Africa. This is due, in large part, to a new elite that emerged at the turn of the millennium. These leaders included Abdoulaye Wade in Senegal, John Kufuor in Ghana, Olusegun Obasanjo in Nigeria and Mamadou Tandja in Niger. They carried the torch of democracy high in West Africa, and they cooperated well among one another. To some extent, the West African experience with autocracy and civil strife may have played a role. Obasanjo himself was a former military dictator. There can be no doubt that approaches they took reflected debate in multilateral settings at that time. Unfortunately these leaders did not have the same impact at the pan-African level, where they basically served as reference points.

What is being done to instil a democratic culture within the armed forces of the ECOWAS countries?

Civil-military relations in almost all the ECOWAS countries have been realigned to conform to the norm of civil oversight of the military. The immediate post-independence era saw a situation where civil-military relations was one of co-optation. The military was virtually an adjunct of the ruling parties. Today, the military is subjected to parliamentary oversight. In Ghana, for instance, the military budget is subjected to parliamentary debate and approval. The parliament may summon the minister of defence who must then answer legislators’ questions. Public audits are made of defence management and procurement. Generally speaking, the military is designed to be an institution of democratic governance.

Has the mindset of the military top brass changed accordingly?

In West Africa today, the top brass is generally oriented towards the consolidation of democracy. I think that the absence of coup mentality among them has to do with three interlinked forces:

- In international arena, coups are unpopular. Coups used to have patronage from either the East or the West blocs of the Cold War divide. Today, the UN condemns coups. Besides, several of the regional bodies have protocols that prohibit the unlawful change of government. The African Union adopted one in 2001, and ECOWAS did so in 2004.

- Many of the top brass are now highly educated, so their appreciation of the global order has grown, and they understand the need for the consolidation of democracy.

- The military is more engaged in domestic roles such as ensuring security and non-conventional assignments including peacekeeping and engagements in low-intensity conflicts. Their training and orientation reflect that focus.

International organisations emphasise good governance and their peacekeeping missions can be career opportunities – does that mean that the top brass has personal incentives to not topple their own governments?

It is true that peacekeeping has become a source of wealth both for the soldiers and for the participating countries. But I do not see that as the main reason why there is no coup mentality among the top brass of the West African armed forces. After all, troops from authoritarian-rule countries do service as international peacekeepers, so national governance is not a pre-condition for becoming involved in missions.

Would you say that West Africa has learned the lessons of military dictatorship and civil strife?

That would be over-optimistic. It is a mixed bag. The top-brass may have learned some lessons, but I doubt that their insights have taken deep root in society in general. Global dynamics were what drove democratisation in the first place. Under pressure from within and from the international community, especially after the end of the cold war and the demise of communism – and with it, monolithic types of governance – there was a return to civil rule all over Africa. But we are back to square one. Bad governance and corruption are common. The abuse of state resources and institutions is the order of the day. We still witness cronyism, clientelism, exclusivism, vengeance politics, profligacy, vote-rigging et cetera. These are the things that triggered coups in the past.

But the military dictators never solved the problems.

No, the military leaders were soon deeply implicated themselves. The fact is they did not understand Africa’s set of problems and did not diagnose them well. They fell victims to the imperatives of the inequitable global division of labour. They were captives to the very ills – corruption especially – which were the basic accusation against civilian rule and which they vowed to uproot.

Is the era of military coups over in West Africa?

It is actually difficult to say emphatically that it is over, since the ingredients for coup-making are all still prevalent – basically the question of bad governance. The big issues are corruption and profligacy, cronyism and imprudence in economic governance. Moreover, conspiratorial coups tend to emanate from middle-level officers and below, not the top brass. So coups are still possible. But I agree that ECOWAS has certainly made it more difficult to stage them – and to prevail in power afterwards. The coup in Mali in 2012 was reversed fast.

To what extent are the armed forces of ECOWAS nations involved in pan-African peacekeeping?

The armed forces of ECOWAS have cooperated on tackling and reducing tensions within their own region, but they are not involved collectively outside West Africa. The African Union (AU) has two overarching mechanisms that were established to strengthen democratic governance and attain peace and security; namely, the African Governance Architecture (AGA) and the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA). ECOWAS has heeded to the call by the AU, as part of the APSA, to establish a Standby Force. True, it was to have been established by 2010. The date was shifted to 2015. It is still yet to be fully established. Some collective exercises have been held by the joint forces of ECOWAS in Nigeria, Benin and Mali, all in preparation towards the full realisation of the AU Standby Force brigade.

Vladimir Antwi-Danso is the dean and director of academic affairs at the Ghana Armed Forces Command & Staff College (GAFCSC) in Accra.

vladanso@yahoo.com