Heat

Our cruel summer days

An unprecedented heat wave just ended. In May, the temperature rose to 48 degrees Celsius in central India, causing discomfort, unwarranted school holidays and power cuts.

In our Santal tribal villages of West Bengal, summer is a tough time. This season is marked by burnt grass in the fields, leafless trees, dried-up ponds, cracked land surfaces, hot winds and sunstroke deaths. Noon is the worst time. The cries of cows and buffalos haunt our villages. The poor beasts crave water and lick their own urine.

This year, I experienced what summer means to the villagers of Khiribari, a sleepy Santal hamlet near Maheshpur in the Indian state of Jharkhand. They have no electricity – but an acute water problem. I met a nine year old girl, Lakhi Murmu, at the narrow well. She had an earthen pot, a bucket and a rope. She had come to collect water from what was only a very slow trickle, only flowing drop by drop. She told me it took hours to fill the pot: “My mother is sick and could not collect it, so I am here to do it.” Other villagers had come to fetch their water before dawn.

The children, elderly people and domestic animals are helpless during summer in our villages. To evade the tremendous heat they sit under the trees and while away their time, sometimes doing handiwork like making of bamboo baskets or stitching brooms.

I asked an elderly man at Khiribari: “What was the summer like a decade ago?” He said that things used to be much better: “Our village had everything – fertile land, green grass, plenty of fish, crabs, snails in the river.” He pointed out that this was the reason “why our forefathers selected this land to build our village.” Stating that his community ended up with nothing, he asked: “Has God maybe forgotten us?” He does not know that it is not God but human beings who are responsible for the climate change. In a remote Santal village, the difference is small. Disadvantaged rural communities have no choice but to accept what they cannot influence.

In spite of all the hardships, Santals look forward to this summer season for some happy reasons. This is when some of the most joyful events take place. “Bapla” (Santal weddings) are celebrated in April, May and June, the hottest months. As the scorching winds blow, the sound of marriage drums are heard in the villages.

The entire Santal villages participate in the rituals and festivities of a marriage. It goes on for five days and nights with songs, dances and the drinking of rice beer. From miles away, people can hear the sound of drums and flock to attend a marriage. The hardest time of the year is thus also a time of joyful celebrations. A newly-wedded couple instills a new sense of vigour in a village, proving that life goes on.

We all look forward to the next season however. We long for lightning and thunder behind black clouds to augur the arrival of the monsoon. The onset of the rains means relief from the heat and therefore triggers a great sense of joy in the villages.

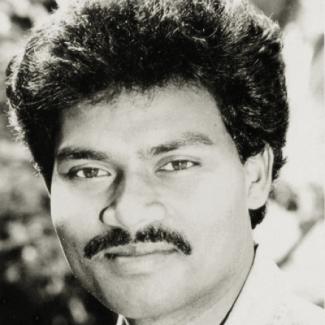

Boro Baski is a teacher and social worker with the Gosaldanga Adibasi Seva Sangha, a community-based organisation in the Indian State of West Bengal.

borobaski@gmail.com