AIDS prevention

A monthly shot of hope for people living with HIV

In Uganda, where about 1.4 million people live with HIV, a new antiretroviral drug is redefining what life with the virus looks like. The injectable treatment, known as Cabotegravir-LA, administered once every two months, has begun rolling out early this year in pilot programmes across the country. For many, it represents not just a new drug, but a renewed sense of freedom and dignity.

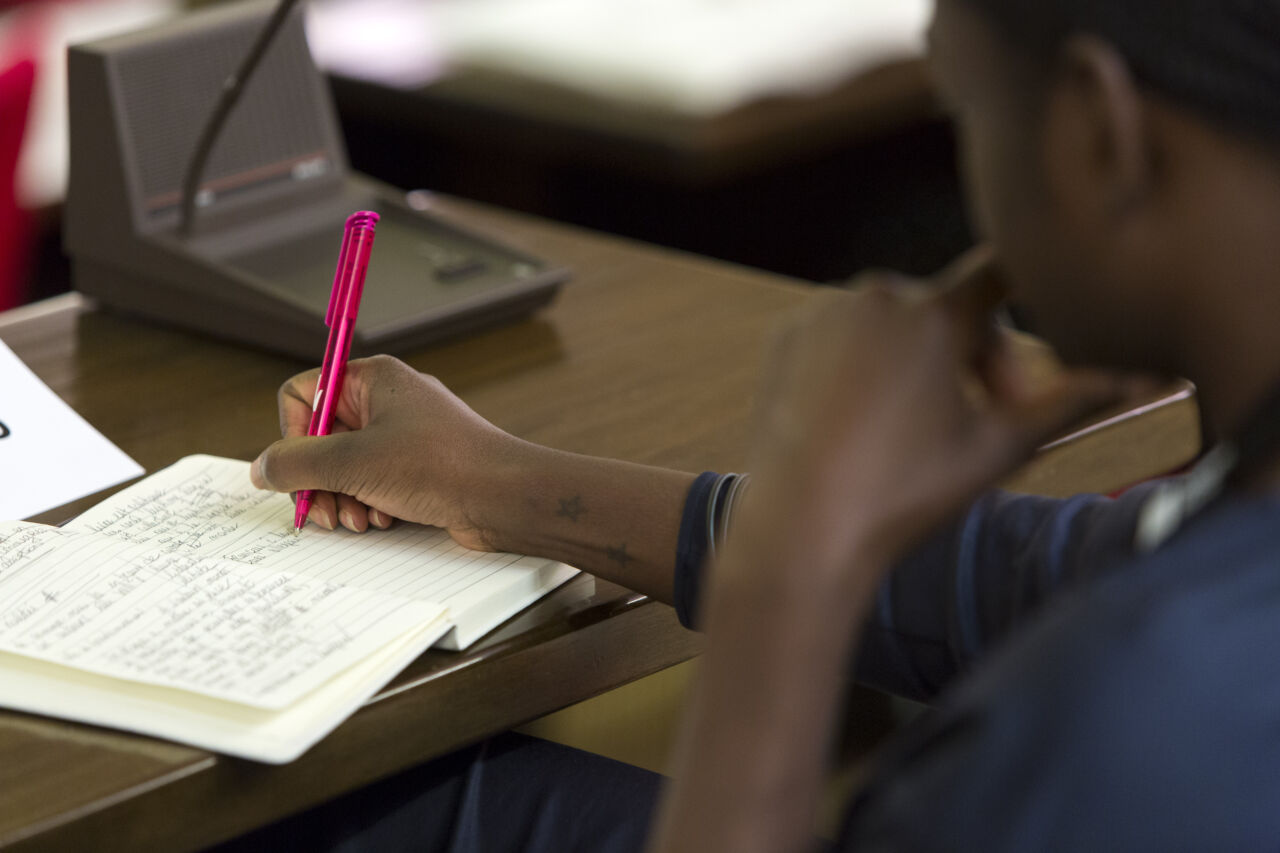

Until recently, people living with HIV had to take daily oral tablets – a constant reminder of their status and, in many cases, a source of stigma. But now, with the long-acting injection, this routine is changing.

“I hide my HIV pills because even in my own family, people whisper,” says 36-years-old Beatrice Nanyonga, a primary school teacher from Mukono, a city 15 kilometres east of Uganda’s capital Kampala. “But with this new drug, I will only go to the clinic once every two months for my injection. It’s private, it’s simple, and it feels like I’m getting my life back.”

The initial results of an earlier pilot study are promising. The study had been launched by Uganda’s Ministry of Health, in collaboration with the Joint Clinical Research Centre (JCRC) and international partners such as UNAIDS and ViiV Healthcare.

The injectable could be a game-changer in retention and adherence. Health workers believe that patients who miss pills or default on treatment will now come more regularly for their shots.

“Promising solution”

Cissy Kityo, Executive Director of Uganda’s Joint Clinical Research Centre, says the new long‑acting injectable regimen is a “promising solution for improving adherence and quality of life among HIV-1 patients in the region.” The new treatment reduces the psychological burden and simplifies care.

David, 28, a resident of Katwe in Kampala who has lived with HIV for a decade, says that the new drug has brought emotional relief. “It’s like a dark cloud has lifted. I used to dread swallowing pills every morning, and it felt like a daily punishment,” he says. “With this new drug, I will be able to go about my day without thinking about HIV all the time.”

But the treatment is not just about convenience, it’s also about improving health outcomes. Researchers found that long-acting injectables maintain viral suppression just as effectively as daily oral regimens and in some cases improve adherence rates.

At a clinic in the district of Masaka, the peer counsellor and HIV advocate Namirembe says that the injectable will reduce stigma in community groups. “People will be able to come together to share their stories without fear,” she says. “This drug will restore confidence.”

Yet, accessing Cabotegravir-LA will pose a main challenge. The injectable remains expensive and requires cold-chain storage, limiting its availability in rural or under-resourced health facilities. Activists are now calling for price reductions and wider distribution.

“We are hopeful,” says Nancy Kemirembe, a nurse in Kampala. “If this can be scaled across the country, we will see a new chapter in HIV care where patients are not just surviving but truly living.”

Whereas challenges remain, Uganda has made steady progress in reducing new HIV infections and expanding access to antiretroviral therapy. The country’s target is to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030.

Sheillah Abaho is a Ugandan writer based in Kampala.

sheilaabaho2@gmail.com