Refugee integration

The challenge of starting over

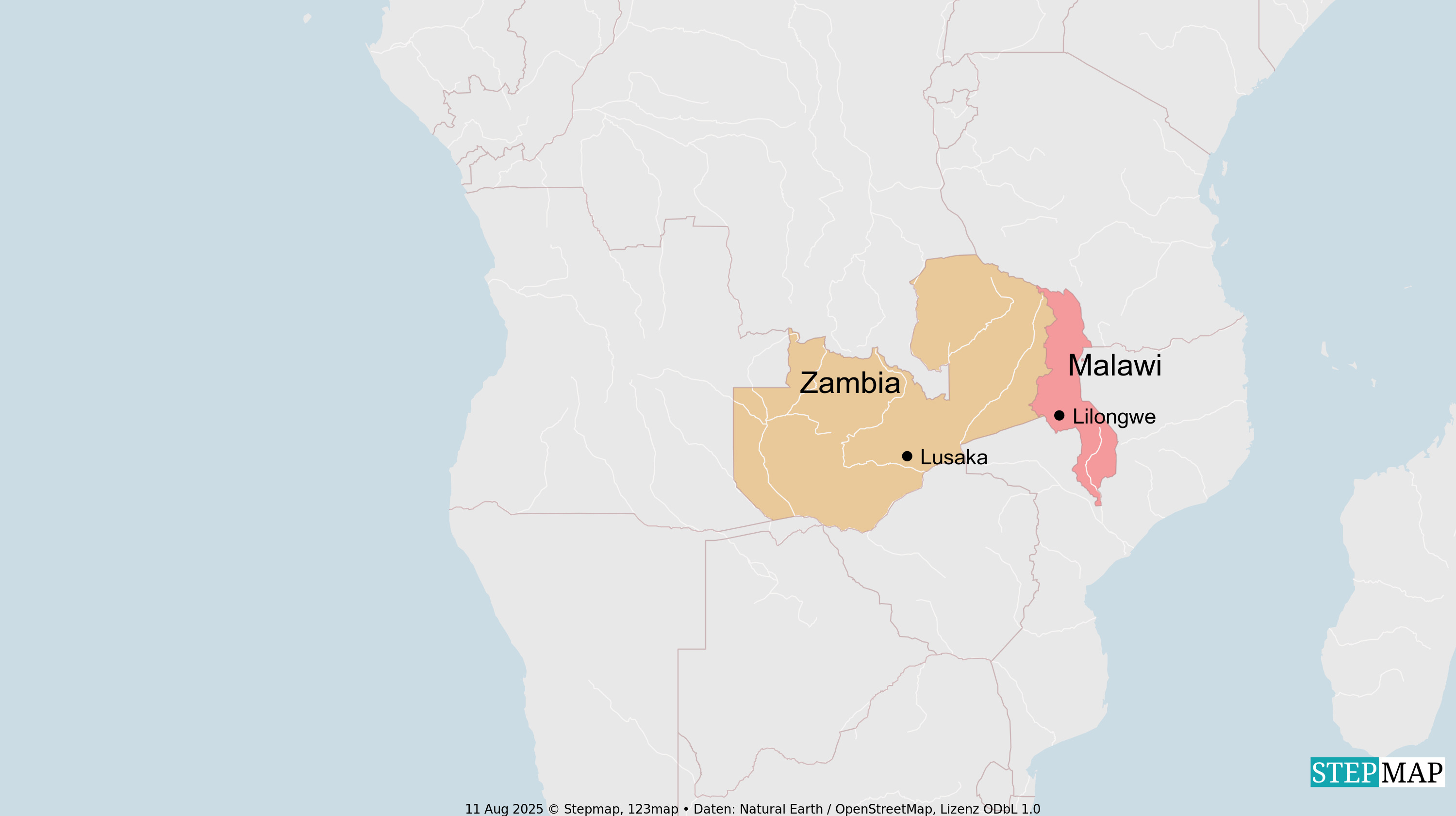

In recent years, the number of people forced to leave their homes has more than doubled. By mid-2024, over 122 million people were displaced, up from around 43 million in 2012. These figures don’t yet reflect the full impact of more recent conflicts, including those in Gaza and Sudan. Most of those displaced remain within their own countries, but many also flee across borders, often to neighbouring nations.

People are forced to migrate for many reasons: war, violence, persecution, natural disasters and the growing effects of climate change. Many LGBTQIA+ individuals are also forced to leave their homes due to discrimination and violence, especially as dozens of countries continue to criminalise homosexuality.

Contrary to stereotypes, over half of the world’s displaced people are women and children. Women face particular dangers, including a greater risk of sexual and gender-based violence, while men are more likely to suffer physical harm.

Finding safety is not easy. The journey to refuge can be just as dangerous as the situation being escaped. People crossing borders may face detention, torture, and deportation. Migration routes are often deadly, with thousands of people drowning or dying along the way. Survivors arrive in refuge deeply traumatised, often having lost loved ones and endured unimaginable hardship. Many have significant physical and psychological health issues.

Integration is not only a personal journey

When they finally reach safety, forced migrants must navigate complex and often hostile immigration systems. In some countries, asylum seekers live in poverty and uncertainty for years while waiting for a decision on their status. This waiting period, combined with the fear of being returned to danger, has serious psychological effects. People are often not allowed to work or study and must endure long periods of isolation and inactivity.

At the same time, once they have refugee status, they are expected to rebuild their lives in a country that may be completely unfamiliar. They have lost homes, possessions, jobs and sometimes even their children or parents. They must now adjust to new cultures, climates, languages and ways of life. In this context, they engage in the process we call integration, or learning to live and participate in a new country.

Integration is not only a personal journey but also a political one. Successful integration helps people feel a sense of belonging and recover from trauma. It is viewed as essential by host societies, as integrated refugees are more likely to contribute socially and economically. Increasingly, public and political support for refugee resettlement depends on how well refugees are perceived to be integrating.

Integration is multi-faceted. It includes finding housing, work and healthcare, building social connections, learning the local language, gaining legal rights, and feeling emotionally connected to the new country. These areas are all linked. A person can’t look for work if they’re unwell or can’t speak the language. They may not feel they belong if they’re isolated or face discrimination.

Integration is a shared responsibility. It depends not just on refugees but also on host governments, institutions, employers, the media and local communities. Racism or anti-refugee attitudes can create huge barriers. There is clear evidence that discrimination harms mental health and makes it harder for refugees to feel they belong or to thrive.

What’s behind poor integration outcomes?

Many countries have integration programmes that offer language classes, job trainings, or help developing employability. Yet refugees struggle more than other migrant groups to find employment or learn the language. It can take up to 10 years for refugee outcomes to match those of other groups, and women often remain excluded even after that time.

Negative integration outcomes can worsen trauma and increase a sense of dependency, while successful integration improves wellbeing and enables refugees to contribute. So why are outcomes often poor?

First, it’s vital to understand that refugees face unique disadvantages. Unlike other migrants, they didn’t choose to leave their homes or plan their journey based on job prospects. Many have experienced deep trauma and arrive with very few resources. They don’t know how systems work, may lack qualifications or documents, and often don’t have friends or family to support them. Some women have no formal education or experience of working independently.

Second, many struggle with complex health problems. Even after physical injuries are treated, psychological trauma can take years to heal. Hearing news from back home or remembering past events triggers emotional distress with individuals experiencing vicariously the traumas of loved ones back home. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) can affect sleep, memory, concentration, and cause anxiety and social withdrawal, all of which make learning or working very difficult.

Despite these challenges, many refugees, especially men, are eager to work and support their families. Most come from cultures where relying on government benefits is unusual, and the idea of not working is deeply uncomfortable. Yet they face a tough job market, lack of networks, language barriers, and prejudice from employers who may be reluctant to take a chance on someone with no host country qualifications or experience.

The situation can be even harder for women. They are often more deeply affected by trauma, loss and isolation. Many lack confidence, especially if they had little education or work experience before fleeing. Some are single parents or have young children and are afraid to use childcare, especially if they have experienced family separation or loss. Many language classes don’t offer childcare, further limiting their ability to learn and engage.

What can be done to improve integration outcomes?

Some countries have better systems than others. Sweden and Australia, for example, offer structured integration programmes that include language learning, childcare and support from caseworkers. These caseworkers refer refugees to services like psychological support or community groups where people can speak their own language and connect with others. This kind of support network helps refugees build confidence, learn about the new culture, and make friends.

Mentoring schemes and community sponsorship programmes are also helpful. Being paired with a local volunteer or family can make a huge difference in helping refugees navigate new environments, feel welcome, and access opportunities. These small connections can help people feel less alone and more hopeful about the future.

Even with such supports, many refugees struggle. Too many programmes are time-limited and place too much focus on getting people into work quickly, without addressing the health or emotional needs that must come first. Refugee women in particular are often left behind, especially if they don’t feel ready or able to take on work or study responsibilities.

Long-term success requires a more thoughtful approach. The first step should always be to ensure safe housing and access to psychological support. Until people feel safe and emotionally well, they cannot be expected to learn or work.

Next, language learning must be more flexible and accessible, beginning with everyday communication and progressing to job-related or academic language. Classes should include childcare and take into account different starting points. For some, vocational training may be a goal; for others, it may be higher education. Refugees, like all people, need time, support and choice.

Entering the labour market can be supported through paid internships or training placements, ideally with employers who receive support and incentives to take part. Matching refugees with volunteer mentors or companions, especially those of similar age, gender or background, can offer the kind of informal help most of us get from family or friends.

Importantly, the work of refugee parents, especially mothers, must be valued. Parenting through trauma and in a new country is hard, and many women focus their energies on helping their children adapt and thrive. This role should be recognised, not penalised. When supported properly, refugee children often do very well at school and can be the bridge between their families and the host society. Supporting refugee parents through befriending, volunteering opportunities, or involvement in schools can help them grow confidence and build a life in their new country at a pace that does not cause additional stresses.

Integration is complex, essential and inevitable. Yet many stakeholders lack a clear understanding of what it means to be a forced migrant and the profound difficulties involved in rebuilding a life in an unfamiliar country. Effective integration demands not only empathy for refugees’ experiences but also the active engagement of all stakeholders. This includes the implementation of comprehensive integration strategies, with states assuming responsibility for ensuring that refugees have access to the resources necessary to rebuild their lives out of place.

Jenny Phillimore is Professor of Migration and Superdiversity at the University of Birmingham.

euz.editor@dandc.eu