Potential for violence

The Kalashnikov curse

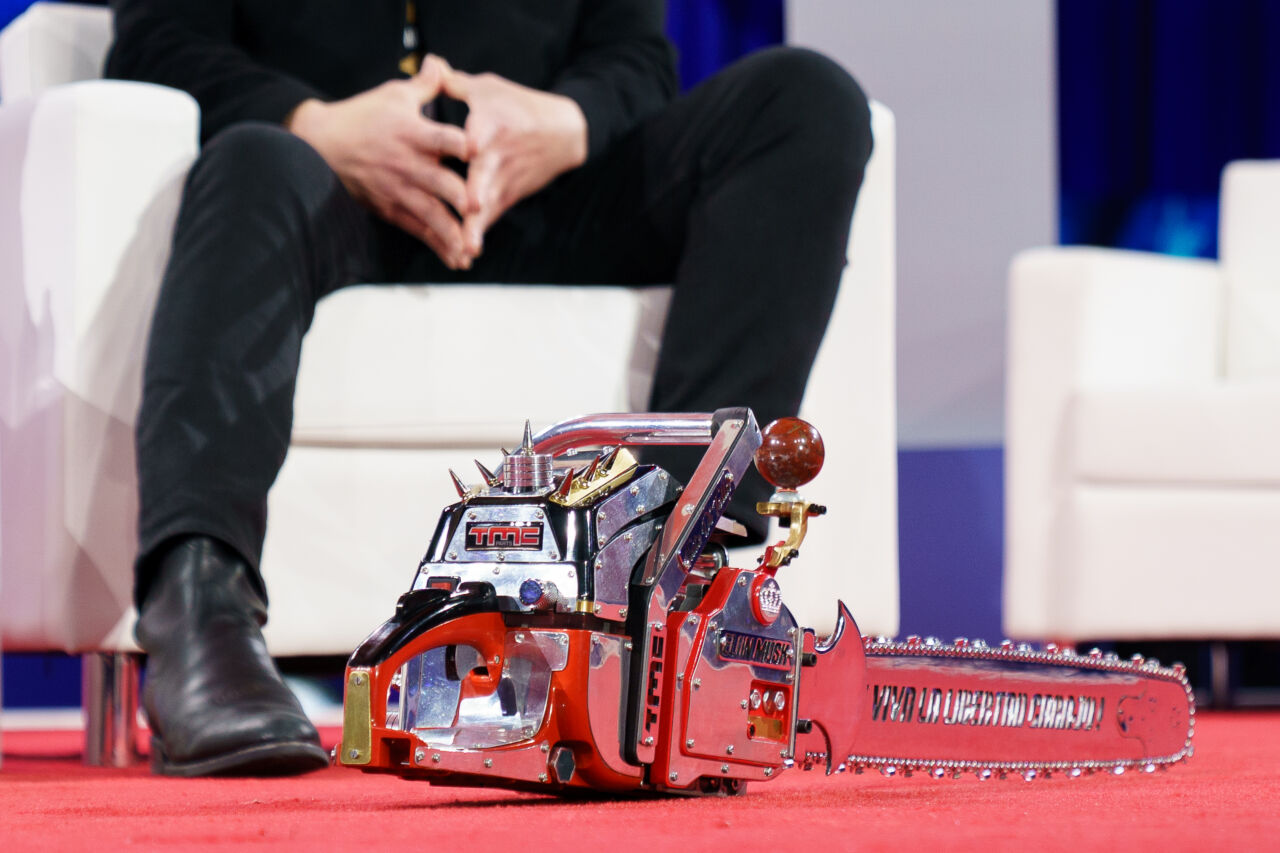

Military arms fall into two separate classes. Major international wars are generally fought with heavy weapons, like tanks, fighter planes and heavy artillery. Such wars have become rather rare. The last one was the Russian-Georgian war in 2008. However, two other types of wars are becoming more frequent: asymmetric conflicts in which a conventional army faces a lightly armed force that uses guerilla tactics and conflicts between equally lightly armed regular or irregular forces. In such conflicts, the arms of choice are small arms and light weapons, known as SALW:

- small arms include rifles, pistols, light machine guns and all weapons that can be carried and operated by one person, and

- light weapons include heavy machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs), man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS), mortars and other weapons that require a small crew to operate.

Though SALW are individually less destructive than heavy weapons, their impact is devastating. They are very common, easy to use, cheap and easy to hide. In the past few decades, SALW have caused more damage and killed more people than heavy weapons have.

Kofi Annan, the former UN secretary-general, said that small arms and light weapons “could well be described as ‘weapons of mass destruction’”, in view of the devastation they cause. Every year, an estimated 50,000 to 100,000 persons are killed with SALW all over the world. The number of indirect deaths of armed violence due to a lack of access to medical care, food or water is four times as high. On top of that, about one million people are injured by SALW use annually. The number of such weapons in circulation is estimated at 875 million, with an additional 700,000 to 900,000 being produced each year. Nearly three quarters are in the possession of civilians.

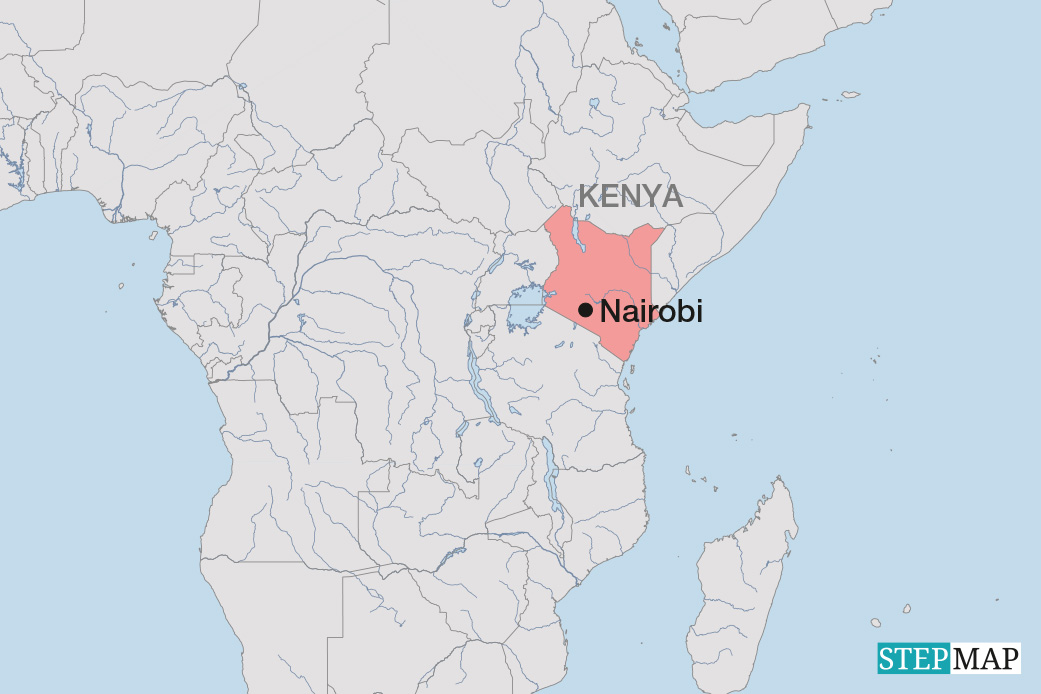

Awash with guns

Africa is awash with SALW, which have played a significant role in all major recent conflicts, including in Darfur, Somalia and Rwanda. There are several reasons why SALW are so prominent in Africa. On the demand side, two factors matter most:

- Warring parties tend to be relatively poor, and SALW are affordable and accessible.

- Civilians’ demand for guns is driven by the fact that many governments are weak so their agencies cannot provide security.

On the supply side, there are three main sources of illegal SALW:

- State actors deliberately provide non-state militias with weapons.

- Government stockpiles are often not managed properly, so SALW are stolen, lost or sold illegally.

- In times of turmoil, weapons are looted from depots and distributed widely, as happened in Libya.

Political turmoil and stockpile management are separate but interrelated issues. Both have contributed to the spread of SALW in Africa in recent years. The most dramatic example was the fall of the Gaddafi regime in Libya. This regime was over-equipped with SALW — and once these weapons disappeared from breached armories, they quickly appeared in black markets. Apart from Mali, the worst-affected country (see box), such SALW have been spotted in places as far apart as the Sinai and Burkina Faso.

Protecting weapon stocks in Africa

Most illegal SALW originate from state stockpiles. While some are deliberately diverted by state officials, others are stolen, lost or sold by corrupt officers. Practices designed to prevent the diversion and misuse of state SALW include physical security measurers such as sturdy buildings, solid locks and secure fencing. Other important components of proper stockpile management are marking and registering weapons and documenting their distribution.

Modern armies and police services typically use elaborate systems to manage their weapons’ stockpiles. They require funding for buildings (including fencing and lighting), surveillance and competently trained staff.

In many sub-Saharan African countries, however, the practices of PSSM (physical security and stockpile management) are not very strong. All too often, international PSSM standards with multilayered security provisions are not observed. Field research by the Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC) has shown that weapons and ammunition are routinely stored in poorly secured stockpiles in South Sudan for example. Some SALW are stored in metal shipping containers, others in traditional mud huts and yet others in open piles on the ground. The country lacks the capacities, resources and infrastructure to comply with even the lowest level of international safe-storage standards.

Poor stockpile management leads directly to two very dangerous phenomena:

- Careful forensic examination of the sites of battles between government troops and rebels in both East and West Africa has shown that about 30 % of all ammunition fired by non-state armed groups was originally from government stockpiles. Armed groups were indeed using the government’s ammunition against government troops. Further research showed that members of the military had sold the ammunition – poorly paid soldiers did so because of need, and senior officers because of greed.

- Self-initiated explosions are even more dangerous. Ammunition degrades with time, notably if stored in inappropriate conditions, with too much moisture or heat. It is then likely to explode by itself. In the past decade, there have been several major explosions of ammunition in Africa. In one explosion in Lagos, Nigeria, over 5,000 people lost their lives.

How to stop proliferation

To stem SALW proliferation and reduce the number of casualties they cause, several things must happen:

- In terms of education, it is necessary to do three things. Technical specialists must be trained to implement proper stockpile management, political authorities must understand the urgency of controlling stockpiles, and the general public must be made aware of the dangers of gun smuggling, old ammunition and related matters. Those who are responsible for stockpile management must change their behaviour and rise to their responsibilities in line with well-documented international standards (see box below).

- In terms of politics, African leaders must understand the risks of uncontrolled proliferation of SALW, consider options for keeping their people safe and pass legislation accordingly. International donors must support initiatives to control SALW.

- Economically, it must be pointed out that good PSSM is far cheaper than the consequences of neglect.

- In technical terms, proper buildings, fencing et cetera are indispensable. If a country cannot afford the most sophisticated systems, it must at least rely on the basic measures to safeguard security.

To stem the proliferation of SALW in Africa, the demand side must be taken into account too. The crucial issue is ultimately that state authorities must enforce the law and provide security in an effective manner to interrupt the cycle of insecurity and small arms proliferation. Civilians’ voluntary disarmament can contribute to SALW control, but it must be based on unbiased, continuing security for all.

Michael Ashkenazi is senior researcher and project leader at the Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC). In recent years he has conducted research in South Sudan, Uganda, Kenya and Guinea Bissau. He has taught at university in the UK, the USA, Canda, Japan and Israel.

ashkenazi@bicc.de

Marc Kösling is research assistant at the BICC and works in the area of small arms and light weapons (SALW) control. Other research interests are international regimes and regional integration.

koesling@bicc.de

Christof Kögler is researcher at the BICC. After working on small arms in the past, he is now focussing on solar-energy issues.

koegler@bicc.de