Police misconduct

Sudden eruption of anger

In early October, a video went viral. It allegedly showed men of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), a Nigerian police unit, killing a young man. Protests erupted fast – first in the major cities of Lagos and Abuja, and then spreading across the country.

SARS has a bad reputation and discontent has been expressed for years. In the years 2016 to 2020, the government announced – four times – that it had disbanded, reformed or scrapped this police unit. This time, it formally replaced SARS with a new unit: the Special Weapons and Tactical unit (SWAT).

SARS was established in 1992. It was meant to fight armed robbery and other serious crimes. Over the years, however, it became known for harassing people and extortion. It was even widely accused of torture and extrajudicial killings.

In 2016, the hashtag #EndSARS began to trend on social media. In the same year, Amnesty International published a report highlighting how SARS officers routinely demanded huge sums of money before releasing persons from custody. In June 2020, the international non-governmental organisation issued another report, documenting human-rights abuses. In one case, SARS officers tortured a 23-year old man they suspected of having stolen a laptop in 2017. In another, they kept a 24-year old man detained for five weeks without allowing him to contact his family or a lawyer or giving him access to medical care in 2018.

In October 2020, after the video incident, protests moved offline. Angry young people rallied on the streets. They used social media to coordinate points of convergence, and soon road blocks made economic activities grind to a halt.

As the protests gathered momentum across the country, a five-point list of demands became popular. It included:

- the release of all arrested protesters,

- justice for victims and compensation for their families,

- the establishment of an independent body to put a check on police misconduct,

- psychological evaluation and retraining of officers and

- better pay for the police so they might finally be adequately compensated.

On the one hand, the government began to discuss the demands seriously, but on the other hand, it once more opted for repression. In the night from 20 to 21 October, armed soldiers were told to disperse protestors who were blocking a toll plaza on a highway in a prosperous part of the Lagos agglomeration. The troops shot and killed several people, triggering violent riots that included looting and even arson.

The anti-SARS protests had erupted spontaneously, based on loose networks of frustrated people. There was no formal leadership. The government thus did not have clearly identifiable people it could negotiate with – and potentially co-opt. On the other hand, no movement leader could assume responsibility in terms of preventing the protests spiralling out of control and turning violent.

In the eyes of the activists, the absence of a recognised leader is a strength. In the past, protest leaders all too often used their position for self-enrichment – or they were silenced by the authorities who arrested them or used even more brutal means.

In the wake of the protests, the government is now cracking down on perceived masterminds. Bank accounts have been frozen and some persons face allegations of financing terrorism. At least one person had her passport seized so she can no longer travel abroad. Dismayed by the audacity and effectiveness of the protesters, the authorities appear determined to mete out punishments.

To what extent the new SWAT will be different from SARS remains to be seen. If it turns out to be no better, youth frustration will keep growing and the government’s legitimacy will further be eroded. Some political leaders seem to believe that aggressive police repression is a sign of strength, but in reality, excessive police brutality indicates inadequate governance – and undermines the credibility of the political leaders.

Link

Amnesty International, June 2020: Time to end impunity.

https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr44/9505/2020/en/

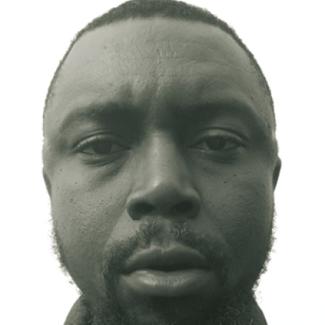

Ben Ezeamalu is a senior reporter who works for Premium Times in Lagos.

ben.ezeamalu@gmail.com

Twitter: @callmebenfigo