Our view

What decent work is all about

Many years ago, I met a woman who really impressed me. I was in Guatemala at the time and had been invited to an exam celebration for student nurses. Out of all the young graduates, only one wore indigenous attire. I learned that she had come from her village to the city years before, without money or secondary school qualifications, to work as a domestic labourer. She went to school on the side and finally completed a training programme. At the ceremony, her parents had tears in their eyes: They knew their daughter would earn a good living.

Many domestic labourers in Guatemala – typically young, indigenous women – still work under precarious conditions. They are poorly paid, lack protections and are often the victims of racism and violence. Nevertheless, they accept these jobs because they offer a small chance to improve their lives. Worldwide, people with low incomes fight under the most difficult conditions for an opportunity to support their families or send their children to school. They migrate, start small businesses and work in mines, factories or on plantations. Some make it, like the nurse from Guatemala; many don’t.

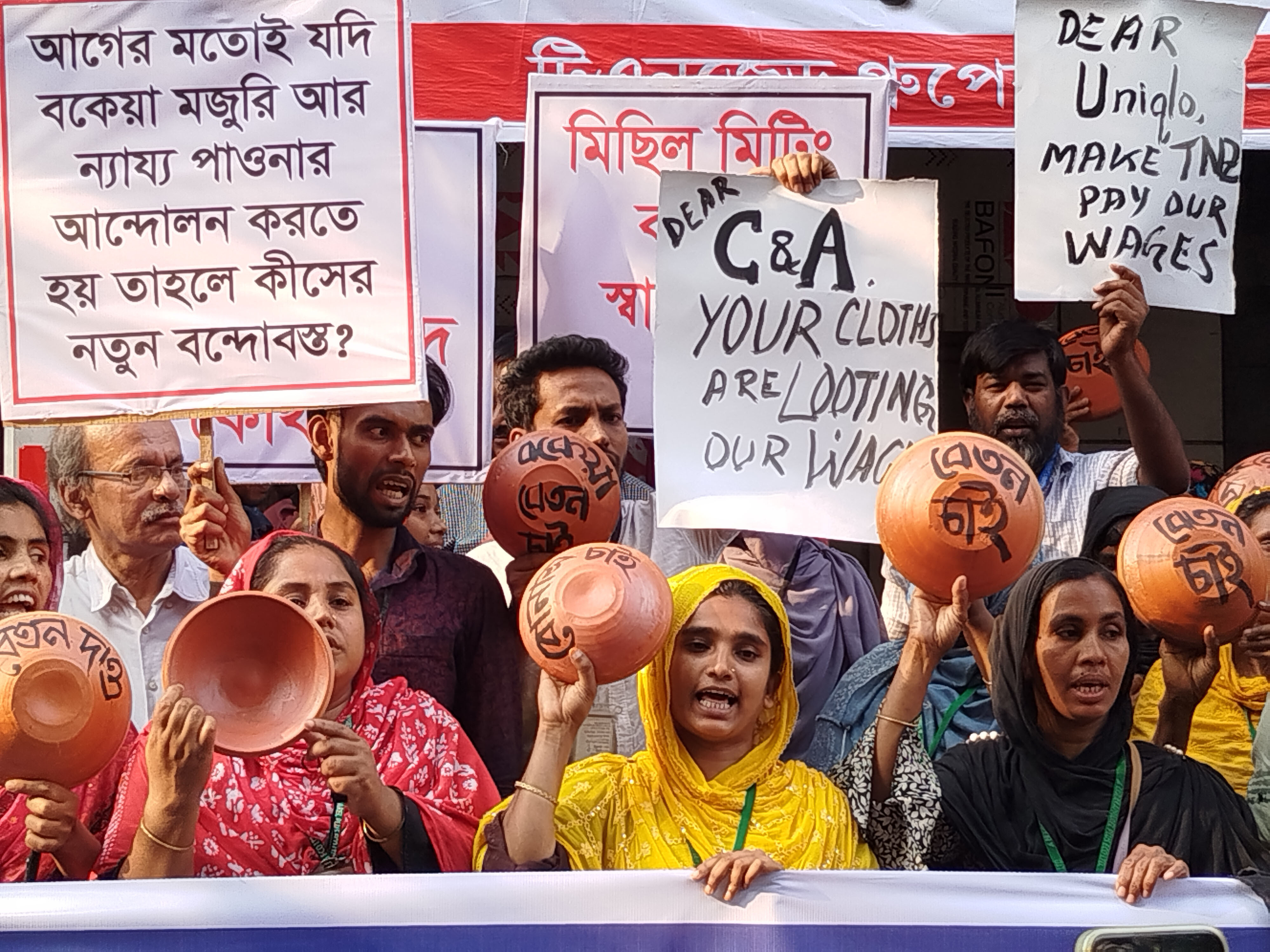

Whether a job presents an opportunity or a risk depends to a large extent on working conditions. That is true of both formal and informal employment: No matter if someone is a salesperson or a factory worker, it makes a difference whether they are able to save money, have time for further education or rest, are shown respect and receive medical care when they are ill. These things are easier to achieve as a collective: Domestic workers in South and Central America have organised across national borders, women working in the informal sector in India are joining forces, and in Bangladesh the textile workers’ union is strong. Together, they are setting wage floors or establishing microinsurance schemes.

But their scope of action remains limited. The global labour market is shaped by old power relations. Far too often, countries in the Global South deliver commodities and cheap labour, while profits and value creation remain in the North. The digital economy has not changed this dynamic: Large tech companies outsource time-intensive activities to low-wage countries. There, people screen violent videos or feed information to AI systems – for a few dollars a day, often without protections.

Whereas US President Donald Trump sees this, absurdly, as a disadvantage for the USA and wants to recall these jobs, in Europe, awareness of suppliers’ working conditions is growing. As of 2023, the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act has required companies to investigate the conditions of their suppliers; next year the EU Supply Chain Act should follow. It remains to be seen what the law can actually achieve; its impact will depend largely on how it is written.

In Kenya, meanwhile, Meta could already be held accountable for exploitative working conditions at one of its service companies. There, content moderators have filed complaints about being required to screen traumatising content on Facebook. At the end of 2024, a court ruled that their lawsuits are admissible. They will not cost the company much: Meta has already moved its content moderation out of the country and the employees have been fired. But the message is clear: Even large corporations should no longer be able to simply outsource accountability.

Eva-Maria Verfürth is the editor-in-chief of D+C.

euz.editor@dandc.eu