Failed state

A slide into war and chaos

Four decades of civil war and poor governance – made worse by foreign intervention – have left Afghanistan a classic failed state. The country is plagued by poverty, corruption and lawlessness. Its traumatised people face daily hardship, deficient state services and rampant insecurity.

The roots of Afghanistan’s decline into failed statehood can be traced far into the distant past, but the immediate origins of the country’s current woeful condition can be found in the Soviet invasion that took place just over 40 years ago, in late December 1979. That invasion followed a coup and was meant to fill a power vacuum, but it led to the 10-year Soviet Protectorate and kicked off the Soviet-Afghan War of the 1980s. The Soviet takeover was viewed with deep suspicion by the United States, which feared the Soviet Union would use Afghanistan as a gateway to the Indian subcontinent to the south and the Middle East to the west.

In the 1980s, Afghanistan thus became the battleground of proxy war between the two Cold War superpowers. The USA did not intervene directly, but supported the Islamist fundamentalists who opposed the Soviet-controlled government.

When the Soviet Union withdrew in 1989, Afghanistan’s troubles were far from over. In fact, they escalated further. The Red Army left behind a vacuum, with no functioning government in place. That meant no one could guarantee law and order or defend the country’s borders. A country that once traded peacefully with its neighbours became an international hub for religious extremists.

In 1992 the Islamist Mujahideen (Jihadists), backed by the West, took over the capital, Kabul. By 1996 the Taliban, a faction of the Mujahideen, had captured most of the country. Far from bringing the hoped-for peace and order, the Taliban’s rise to power opened a new black chapter in Afghan history. What followed was five years of harsh totalitarian rule by this fundamentalist group.

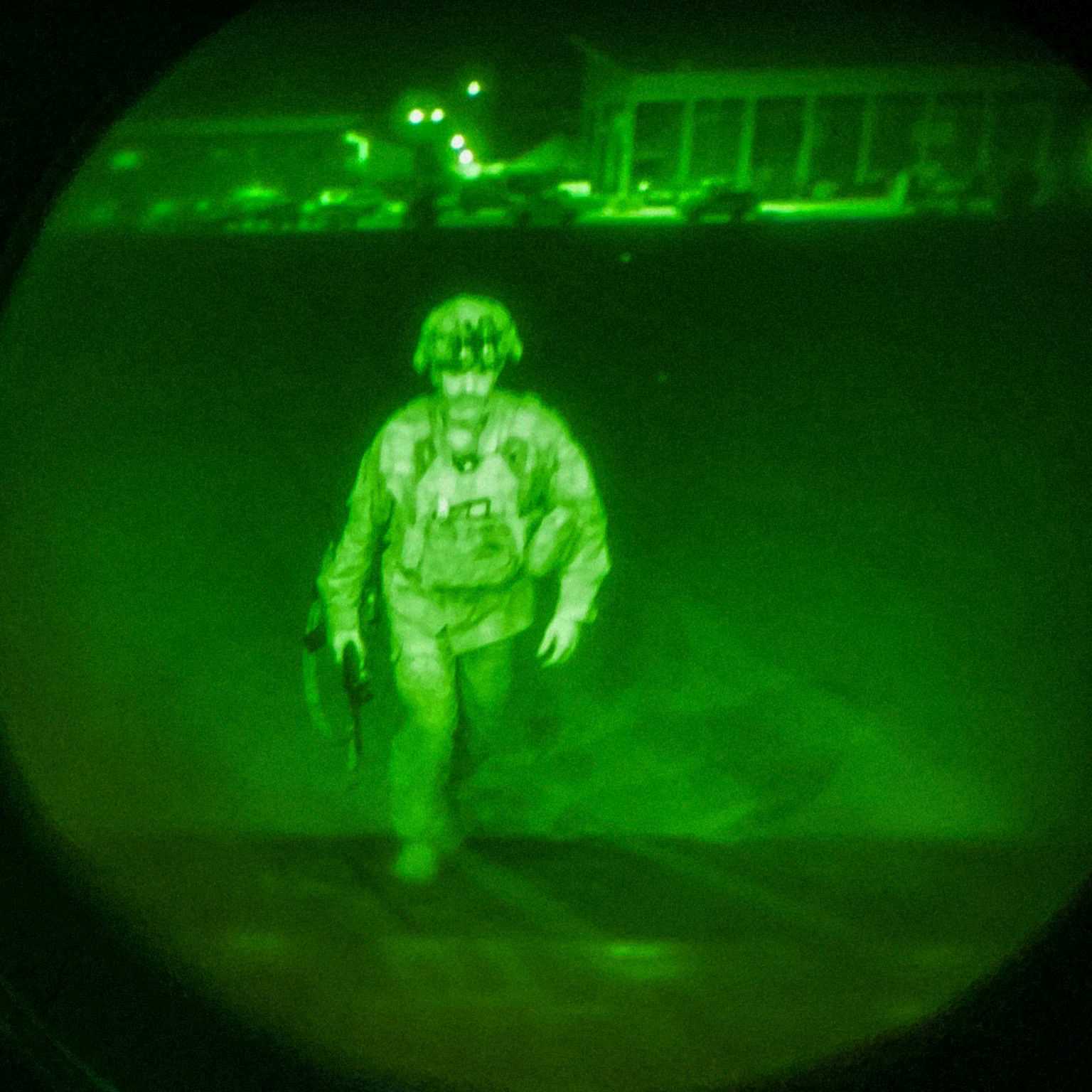

After the attacks of 11 September 2001 on the United States, Washington forcibly removed the Taliban from power. Nonetheless, the Islamists still control much of the country. The Taliban continue to fight against the Afghan government, and civilians continue to be killed. The administration of President Donald Trump signed a peace agreement with the Taliban earlier this year. However, the muteness of the agreement on the future of power sharing, rule of law and women’s rights have rendered the Afghans suspicious with regards to its success.

The casualty figures from all the fighting are staggering. In the years following the Soviet-Afghan War, between 6.5 % and 15 % of Afghans were killed, about 20 % were wounded, and about 33 % fled the country. Among those fleeing were the country’s most educated people.

An economy in tatters

The long and bloody conflict has left Afghanistan’s economy and society in shreds. The Special Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction (SIGAR), the US government’s reconstruction oversight authority, labelled Afghanistan a “failed state” in its 2019 report after evaluating the country’s economy, rule of law, governance and security conditions.

For one thing, Afghanistan still lacks a strong and accountable government that can stand on its own. The last 40 years of conflict have caused the collapse of institutions and a severe weakening of the rule of law. The trust of Afghans in their rulers has deteriorated severely. When a state is unable to enforce the rule of law, people face the grim choice of either taking the law into their own hands or turning to mafia-type militias for protection. Either way, chaos follows.

Afghanistan’s economy is also in tatters. Its infrastructure and communication systems are broken. Food and medical supplies are scarce, as are electricity and running water.

According to the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook database in October 2019, per-person gross domestic product in Afghanistan is only equivalent to the purchasing power of $ 513. This means Afghanistan ranks 177th out of 186 countries in this key measure of wealth, right behind Sierra Leone and Togo.

Moreover, the outlook for rebuilding the country is poor. The country lacks skills and leadership. Many educated Afghans have left and not returned. The massive flight from conflict zones created the world’s largest refugee population until the Syrian War.

Those who remained in the country have been traumatised by the years of war and are poorly equipped to rebuild the country. Most Afghans were illiterate before the Soviet-Afghan War, and the long years of conflict have impeded education. A huge number of young people who grew up during the Soviet occupation have seen nothing but war and have spent their lives being used by power-hungry leaders to fight against each other.

All this has had a massive psychological impact on the Afghan people. After the Soviet invasion, Afghans needed time to grieve, heal physically and mentally, and slowly rebuild their cities, villages and homes. They did not get that time. Making matters worse, in areas controlled by Islamists, people are forbidden the few simple traditions and sources of happiness left to them, such as music and dance.

Instead of healing, people continue to be bombarded by war and destruction. They lack the benefits of an effective government that understands their needs in the face of loss, grief and anger. Foreign powers intervening in the country have not been up to task either. The governments they have been supporting and financing were weak. Afghans’ willingness to obey laws and assume responsibility has been allowed to keep eroding.

Beyond a tendency to lawlessness, the decades of conflict have fostered a streak of belligerence and aggression in a people that once had been peaceful. There is resistance to change. Although some modernisation is taking place in Kabul, most people adhere to traditional, tribal ways of life. Unlike other ties, moreover, tribal identities still inspire a sense of mutual trust.

Inward-looking

The country has become inward-looking. While tourists were welcomed in the 1960s and 1970s, foreigners are now viewed with suspicion. This attitude was promoted by leaders on both sides during the Soviet-Afghan War. Both were eager to discredit the foreign powers supporting their rivals. The lasting result was an increased sense of xenophobia.

There also has been a marked change in the way Afghans view their religion. Before the Soviet-Afghan War, Afghans practiced Islam in a socio-cultural manner and not as a political movement. The Soviet occupation and the proxy war that followed changed that, making religion a politically defining factor.

During the Soviet occupation, traditional Afghans rejected Soviet propaganda against religion and many of them became radicalised. The USA along with its allies Pakistan and Saudi Arabia encouraged the trend toward religion-inspired fighting. Faith-based ideology obviously proves to be powerful in both Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. Islamist extremists who fought the Soviets received huge amounts of financial and military support.

The Soviets and their Afghan proxies played a part in this trend as well. The so called nouveau Afghan-communists tried to force social change without considering people’s religious and cultural sensibilities. Soviet-backed Afghans used harsh methods to impose anti-religion reforms. That made many Afghans receptive to the Islamist message of religion-based resistance.

A country does not fall apart in a year, or even in a decade. It deteriorates slowly over decades. This, unfortunately, is what has happened in Afghanistan. And equally unfortunately, it may take decades more to repair the massive damage done.

Nawid Paigham is a political and economic analyst.

npeigham@gmail.com