Restitution

Giving back stories

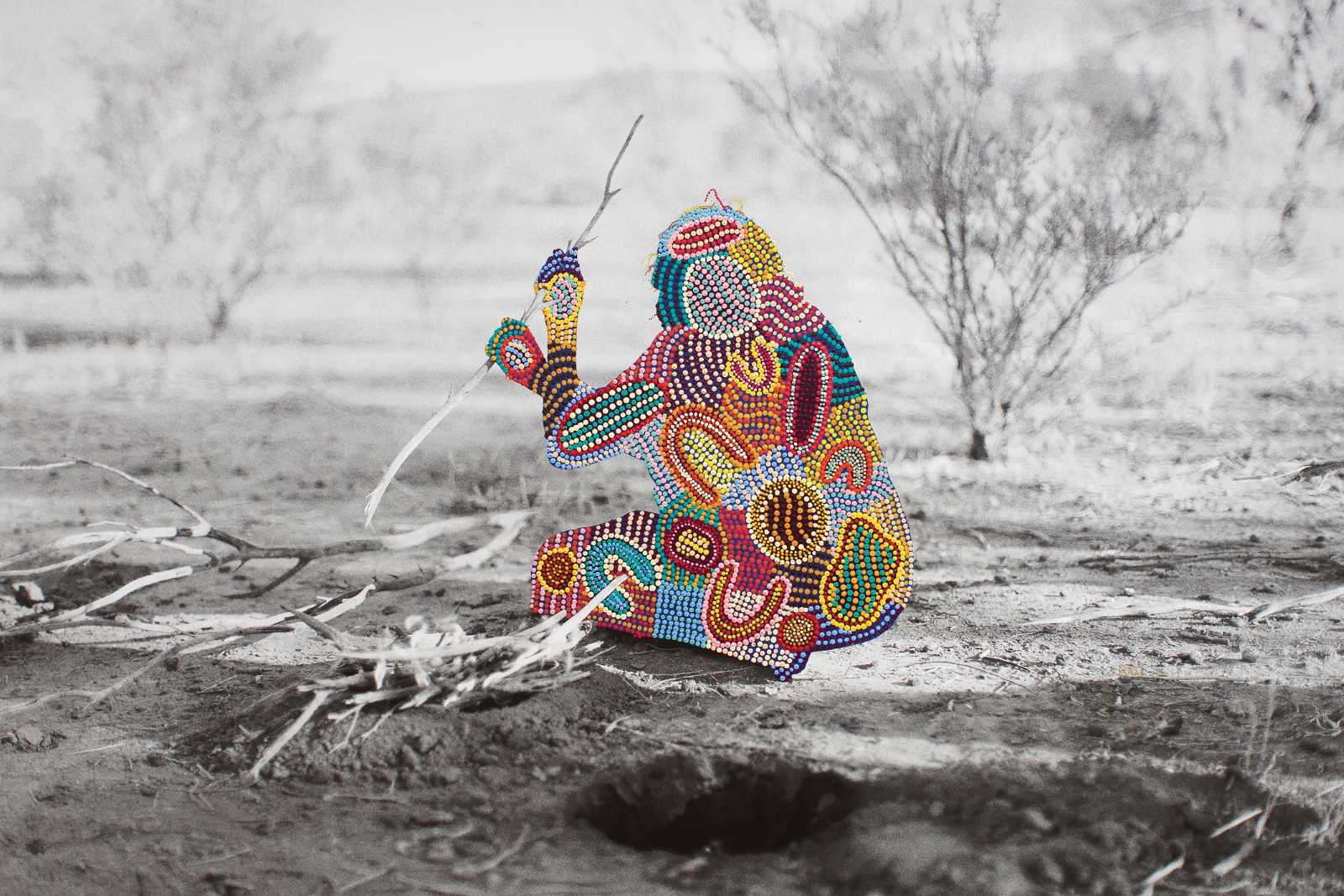

The return of the Benin bronzes to Nigeria has intensified the discussion about material restitution. It is widely known that African countries have long demanded the return of unlawfully acquired cultural property. Its retention in Europe robs them of parts of their identity and history and legitimises the colonial past. Restitution is an opportunity for Europe and the countries of origin to overcome the colonial legacy in this respect.

In this context, greater attention should also be paid to immaterial restitution – the return of historical documents and oral history transcripts and their publication, especially in their countries of origin. In 1998 and 2001, books with texts in the Namibian languages Ndonga and Kwangali were published with the support of the German Embassy in Windhoek. Those texts had been published in Germany in 1957 and 1975, but not in what was then South West Africa.

From 1902 to 1906, the German missionary Julius Augustiny collected folktales of the Kamba in Kenya. In the 1920s, they were edited in Kikamba in the German journal “Zeitschrift für Eingeborenen-Sprachen”. In 2012, they were published in Tanzania in Kikamba with a parallel Kiswahili translation in the book “VAU TENE...” (“Once upon a time...”).

Kikamba is a widely spoken language in Kenya, where most of the approximately 4.5 million Kamba live in the heart of the country, in Machakos County. Kikamba is also spoken in Tanzania by around 12,000 people in the west of the Morogoro region. Thanks to the accompanying Kiswahili translation, the texts are accessible to people throughout East Africa.

Restitution after more than 100 years

The former vice chancellor of Hubert Kairuki Memorial University in Dar es Salaam, Keto Mshigeni, now calls for the return of a book from the German colonial era about the Pare ethnic community. Entitled “Im Banne der Furcht”, it was published in 1922 by the German missionary Ernst Kotz. The book documents a little-known period of regional history. Mshigeni describes Kotz’s book – written between 1905 and 1917 in the Pare region of what was then German East Africa – as a valuable historical testimony. It connects to the documents and publications of the prominent Tanzanian historian Isaria Kimambo, who interviewed Pare in the 1960s and reconstructed their history up to the end of the 19th century. But he did not cover the German colonial period. Today, around 530,000 Pare (also known as Asu) live in the Kilimanjaro region, mainly in the Same and Mwanga districts, and in the Manyara and Tanga regions.

Costly digitisation

As part of the restitution of intangible cultural heritage, the digitisation of the book’s 223 pages of Gothic script as well as its translation into English and Kiswahili should be made possible by German funding. German sponsors have not yet been found.

The translation of “Im Banne der Furcht” and the publication of English and Kiswahili versions would be an important contribution to immaterial restitution, helping the Pare community and other Tanzanians learn more about a previously inaccessible period of their history.

Karsten Legère is Professor Emeritus of African Languages at the University of Gothenburg.

karsten.legere@sprak.gu.se