Carbon credits

Africa is chasing billions

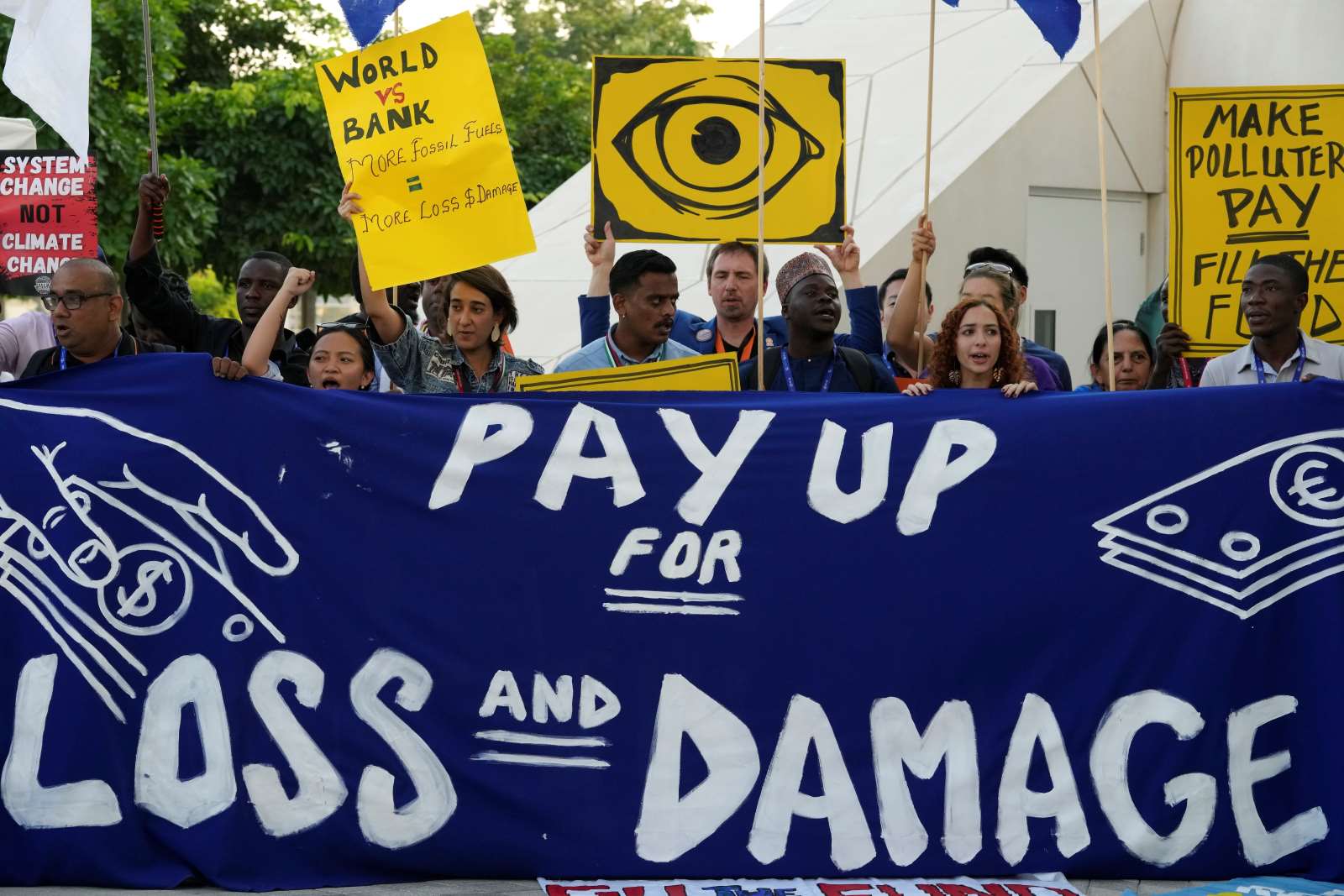

The outcome of the 28th annual Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP28) in Dubai in December was a disappointment to many who had expected it to drive reform, not least with regard to the two main approaches to carbon pricing: carbon markets and taxes.

Important milestones were achieved at COP26 in Glasgow in 2021. Countries agreed to support the transfer of emission reductions, incentivise the private sector and pursue non-market approaches to climate adaptation and mitigation. However, little was achieved at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, and things came to a standstill at COP28.

This is particularly frustrating for Africa, where hopes were high in the run-up to COP28. Two months before the conference, the countries of the continent had agreed on a common position in the Africa Climate Summit Declaration, which proposed a “global tax system including a carbon tax on fossil fuels, maritime transport and aviation”. Africa accounts for four percent of emissions but remains among the regions most affected by the climate crisis.

The global markets for carbon credits and offsets have suffered some serious reputational damage in the recent past. Broadly speaking, emission credits are permits for emissions authorised by a governing body to participants (e.g. companies or countries) in a regulated trading system with a cap. Emission offsets are created, for example, when a company invests in environmentally friendly projects to avoid emissions. These offsets can be traded on voluntary markets.

Despite criticism, revenues from carbon taxes and trading schemes totalled $ 95 billion last year, according to the World Bank. The Bank’s recently published report “State and Trends of Carbon Pricing for 2023: International Carbon Markets” shows that financial flows in the carbon markets have increased.

Research conducted by private-sector entities Trove Research and International Emissions Trading Association indicates that $ 17 billion were invested in carbon markets between 2020 and 2022. As of 2023, the global market for carbon credits is estimated to be worth almost $ 403 billion, according to a study by InsightAce Analytic, another firm. Africa has its eye on this money flow. It can help to close the huge gaps in its climate finance.

“Studies show that with $ 20 per tonne of nature-based carbon credits, $ 82 billion could be generated annually. That’s about one and a half times the money Africa receives in official development assistance,” said Claver Gatete, executive secretary of the UN Economic Commission for Africa, on the sidelines of COP28. According to Gatete, the UN agency is currently in talks with member states to ensure that Africa’s participation in carbon markets is based on “high integrity credits” which make sure the continent is able to unlock benefit-sharing policies, deployment of sustainable decarbonisation pathways and investments in nature-based solutions.

“Next major export”

In 2021, Gabon became the first African country to receive payments totalling $ 17 million from the Central African Forest Initiative to reduce emissions by protecting the rainforest in its Congo Basin.

This triggered a continental race for sovereign carbon-offset programmes. At COP27, Kenyan President William Ruto declared that his country’s “next major export” would be carbon credits. He said this as he joined other African heads of state to unveil the African Carbon Markets Initiative, which aims to unlock $ 6 billion in annual revenues by 2030 while creating 30 million green jobs in Africa and generating 300 million carbon credits.

A few weeks after COP27, Ruto launched an ambitious tree planting initiative that aims to plant 15 billion trees and restore about 5.1 million hectares of degraded and deforested land in Kenya by 2032, with the aim of obtaining carbon credits.

In 2023, the Kenyan leader hosted the first Africa Climate Summit in Nairobi and also positioned it as a platform for developing the continent into a hotspot for carbon credits. The summit ended with pledges for carbon credits worth $ 650 million under the African Carbon Markets Initiative.

The pledge was led by Middle Eastern conglomerates, notably the UAE Carbon Alliance and UAE’s Blue Carbon Company, which signed multi-million-dollar land deals with several African governments to secure and manage forests, wetlands, peatlands, swamps and grasslands, as well as coastal mangrove forests. The governments’ promise is to conserve these areas and generate carbon credits. In return, the conglomerates will sell the carbon credits to companies and governments that want to compensate for emissions and thus fulfil their climate pledges.

There are currently two types of carbon markets:

- In compliance markets, governments set up and regulate an emissions trading system defined by a geographical area with an emissions cap. This is the case with the EU Emissions Trading Scheme. Under such a system, companies and countries that have exhausted their emission quotas can buy unused emission allowances from other companies to continue emitting beyond their quotas. They can also purchase “offset credits” from other countries outside the geographical scope of the scheme.

- In voluntary carbon markets, there is little or no regulation. Companies set their own emission targets and buy carbon credits from willing sellers to cover or offset their carbon emissions.

In Africa, it is mainly the voluntary market that is well established, as countries are slow to create a legal framework that enables a thriving compliance market. However, the voluntary market on the continent is controversial and has been criticised for being opaque, discriminatory, unfair and ineffective in terms of development and climate policy. The environment minister of Congo-Brazzaville, Arlette Soudan-Nonault, described it as an “unregulated Wild West”.

Kenya currently dominates the voluntary carbon market in Africa with projects such as a mangrove restoration initiative and the Northern Rangelands Trust’s carbon projects, according to Kenya’s special climate-change envoy Ali Mohamed. Other countries with similar projects include Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, the Gambia, Ghana, Madagascar, Mozambique, Senegal, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Seven weeks after the 2023 summit in Nairobi, the Kenyan government began forcibly evicting the Ogiek community from their homes in the Mau forest complex, blaming them for the deforestation of more than 2500 hectares. The government plans to fence the forest and plant 4.3 million trees. However, the evictions were temporarily halted by the Environment and Land Court two weeks after they began.

Serious flaws

It is not only in Kenya that Africa’s call for carbon credits, which are touted as nature-based solutions, is being criticised by climate policy think tanks, the scientific community and civil society. They slam various projects on the continent for lack of transparency, lack of equitable revenue sharing, greenwashing and dispossession of indigenous and local communities.

In 2023, the human-rights group Survival International published a report exposing serious flaws in the Northern Rangelands Grassland Carbon Project, one of Kenya’s many initiatives, including lack of prior informed consent and financial probity, opaque benefit-sharing, lack of scientific rigour and governance concerns.

The Oakland Institute, an independent policy think tank based in the US, has warned in its 2023 report that Africa faces “devastating social and environmental impacts”, including “the prevalence of corruption and fraud in voluntary carbon markets”.

According to Anuradha Mittal, Executive Director of the Oakland Institute, the fixation of Kenya and other countries on voluntary carbon markets ignores their failures. Mittal argues that these markets have not led to a reduction in carbon emissions. “Conflicts of interest, fraud and speculation plague these markets, while the expansion of carbon offset programmes and tree plantations leads to the expropriation of community lands to make profits for investors,” she said. “The expansion of carbon markets does not benefit Africa, but perpetuates the status quo of resource exploitation, greenhouse-gas pollution and power imbalance.”

A coalition of civil societies led by Power Shift Africa and Climate Action Network International also published a damning report stating: “Carbon markets benefit polluters, fossil-fuel companies and market brokers. They drive pollution beyond climate limits and are neo-colonial barriers to realising genuine African development pathways.”

If Africa’s participation in the carbon markets is to truly benefit the continent, its people and its nature, the situation must develop differently. Fair cost sharing, transparency, respect for indigenous land rights and truly sustainable projects without greenwashing must take centre stage.

Wanjohi Kabukuru is a Kenyan journalist and specialises in environmental affairs.

wkabukuru@gmail.com

https://twitter.com/wanjohik