Debt restructuring

Cold war inside the G20 Common Framework

After multilateral initiatives made it possible, many of the countries concerned saw progress again. Roughly summarised, the deal was that in return for reduced debts, they would invest more in their people’s welfare. At the same time, they were expected to ensure macroeconomic stability in the future.

Western donor governments basically want to tackle debt crises this way again. However, they are no longer the only relevant players. Zambia has borrowed more money from large emerging markets and the private sector. Typically, the countries that are currently heavily indebted owe the latter two categories more money than they do long-established bilateral donors and multilateral institutions.

The Chinese perspective

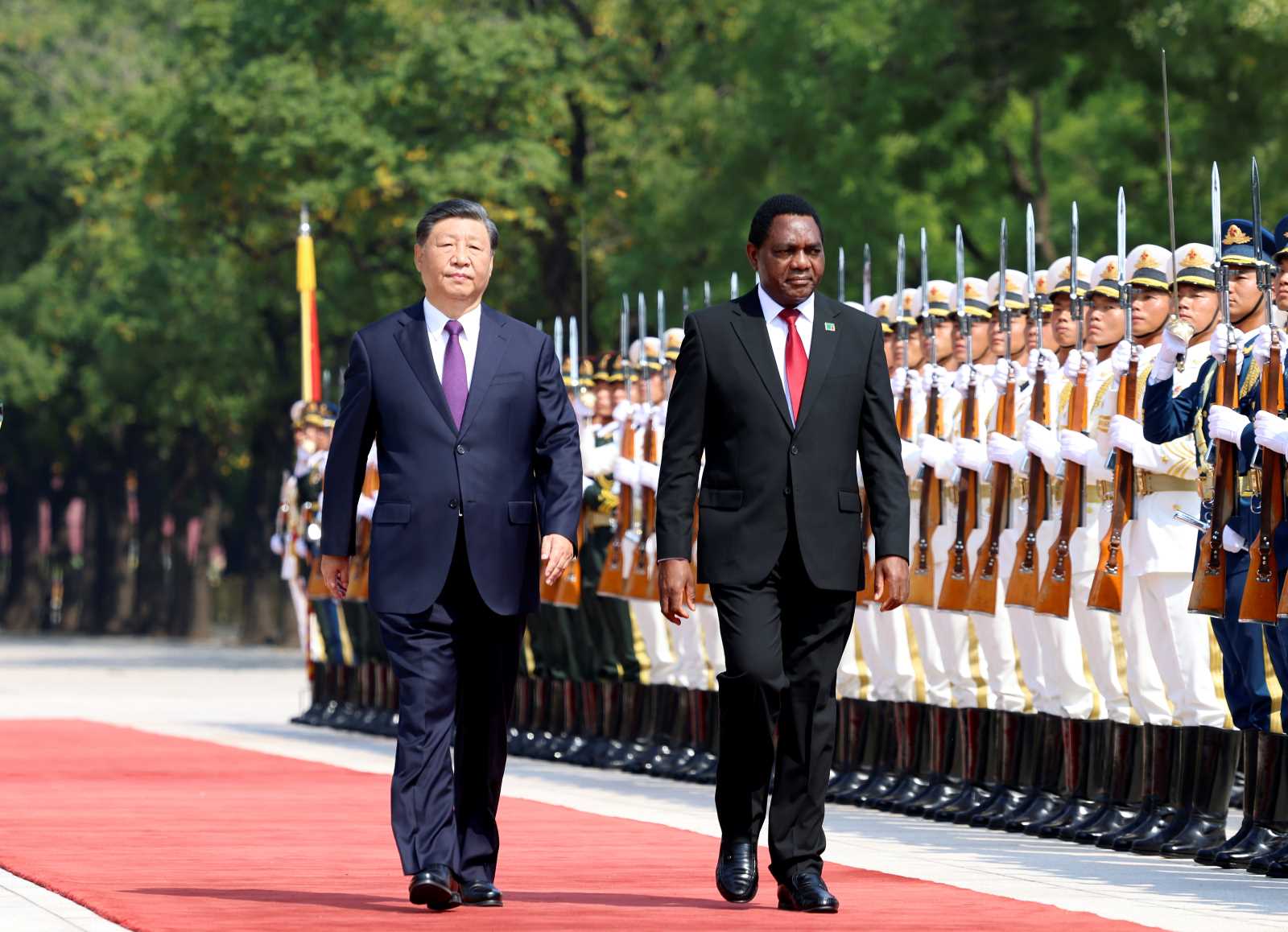

The governments of emerging markets, and especially China, see things in a different light than those from established economic powers. They resent western influence and sometimes argue that western loans basically serve hegemonial purposes. At the same time, they want to enhance their own reputation and gain a stronger clout in world affairs. In Chinese eyes, developmental lending contributes to both. The irony is that US leaders have accused them of setting up debt traps.

That was probably not their intention, but it is true that China’s leaders have failed to learn the lessons of the west’s failed development lending in the past century. Lenders from emerging markets have a general tendency to disregard issues of governance, which are essential for prudent budgeting, and they claim they don’t want to be involved in domestic affairs. Moreover, there are disputes regarding whether multilateral institutions like the World Bank serve western interests or global purposes.

Related controversies make agreements difficult. Unlike the established donors, China is reluctant to forgive debt, but rather generous in postponing payments. For obvious reasons, both the established donors and those from emerging markets pay close attention to not restructuring debts in ways that might ease the other side’s burden.

Private investors, by contrast, are only in it for the money. When interest rates in high-income countries dropped to record lows after the financial crisis of 2008, some started to invest in developing countries and emerging markets where returns looked better. Their action was never geared to developmental goals, but only towards good financial returns. They will do whatever they can to maximise returns. It makes things more complicated, however, that the commercial creditors that have lent money to Zambia include state-owned Chinese Banks. They may be focusing not only on financial returns, but geopolitical considerations too.

Why compromise is possible

In spite of diverging interests, compromise is possible. The point is that all parties know that they will never get their money back in full from an insolvent debtor. Aware of mounting problems internationally, moreover, the G20 had set up the Common Framework for Debt Treatment (CF) at its summit in Saudi Arabia in 2020. The idea was to provide fast and conclusive debt restructuring to low-income countries in need. The intentions were good, but implementation was often unconvincing. In regard to Zambia’s debt crisis, observers have spoken of “civil war within the CF”.

The experience shows that a stronger global framework would make sense. Binding international rules for restructuring sovereign debt after the default of a government would be helpful. Concluding a series of voluntary restructuring deals with different partners, after all, is not only tortuous for the government concerned – it also prolongs the economic slump that makes its people, who did nothing to cause the sovereign debt crisis, suffer serious hardship.

Beaulah N. Chombo is a Zambian economist and analyst.

beaulahchombo27@gmail.com

Charles Chinanda is a Zambian economist and analyst.

charleschinanda@gmail.com