Our View

Waithood – endless adolescence

According to the UN, persons aged 15 to 24 belong to the age group defined as youth. For socio-economic reasons, however, even persons over 30 are often considered to be “girls” or “boys” in many places. Even where social norms expect young persons to become independent fast, serious obstacles stand in their way. The obstacles include lack of access to

- good education and vocational training,

- influential networks,

- policy-making forums and

- decent employment.

The implication is that young people fail to acquire “attributes of adulthood”. According to Alcinda Honwana, the Mozambican social anthropologist, these attributes include living in one’s own home, having a job, starting a family and being able to financially support relatives.

Waiting for adulthood

Anthropologists call this kind of waiting for adulthood “waithood”. It is especially prevalent in Africa, the demographically youngest continent with an average age of about 19. However, masses of young people face tough labour-market competition in other world regions too. Whether in Lucknow or Lagos, it is not unusual for someone with a college degree in business administration to still live with their parents in a tiny home and earn money in the informal service sector, for example as a street vendor.

Many young people refuse to patiently accept waithood. Throughout history, the young generation drove protests. Examples in recent decades included the Occupy movement responding to the global financial crisis of 2008, the Arab Spring, Fridays for Future and Black Lives Matter. With international repercussions, young people made themselves heard again and again.

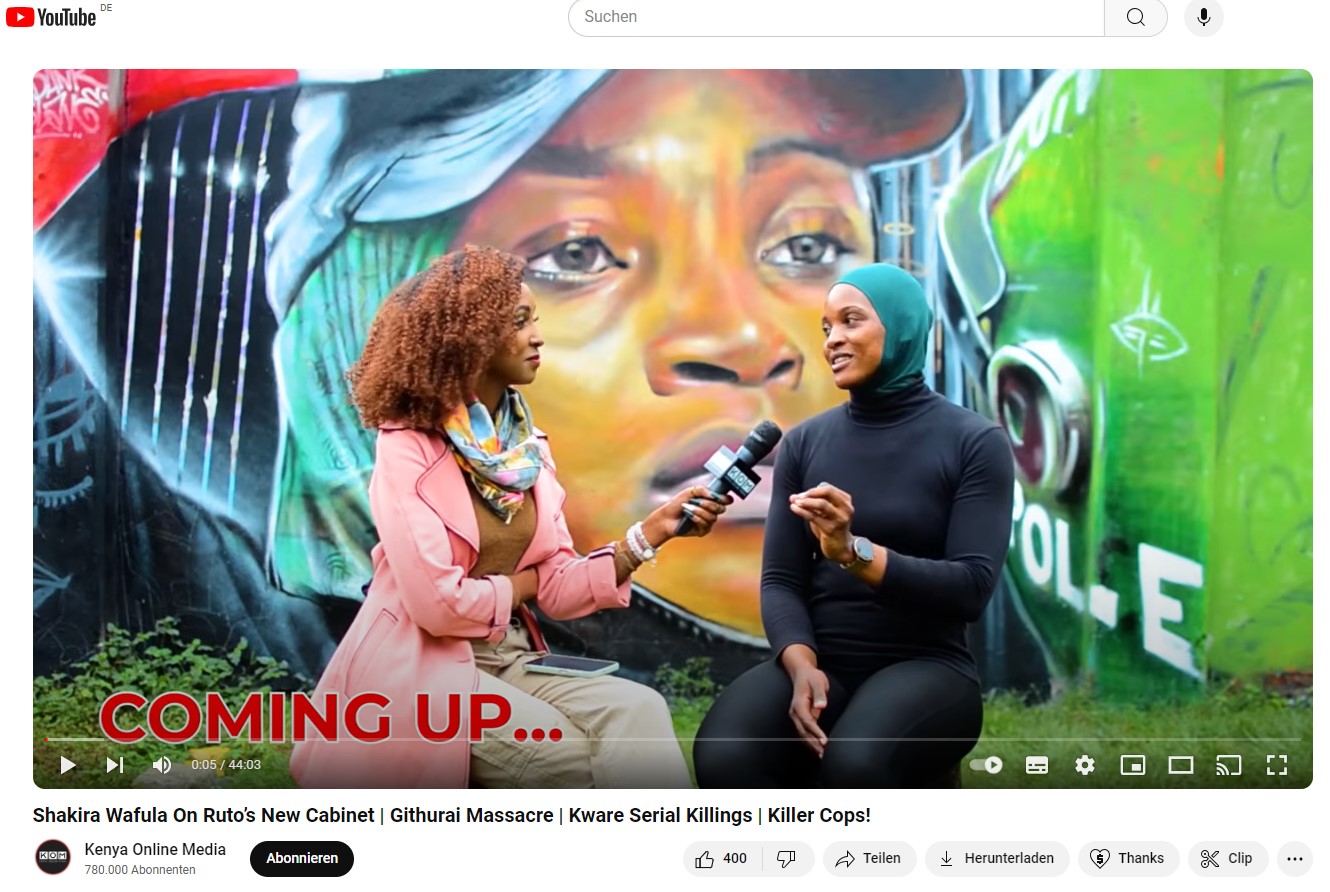

Kenya is currently experiencing the impacts of such protests. The entire cabinet was dismissed because of the youth movement that rose up triggered by President William Ruto’s tax plans.

Inspired by those events, young people have started mobilising in Ghana, Malawi and Nigeria too. Earlier this year, young activists contributed to Senegal holding presidential elections even though the incumbent head of state, Macky Sall, wanted to postpone them. He was term-limited and no longer in office.

Radicalisation

Some trends are worrisome, however. In the recent European elections, right-wing populists won increased support from the age group 16 to 24. These parties excel in using social-media platforms to reach out to youngsters. So do radical Islamist groups.

Extremists do what they can to exploit the personal insecurities and the longing to belong which mark adolescence. Democratic governments and parties must serve young people better. Education must be accessible, and it must be good. It must include competent citizenship, media literacy as well as the basic facts regarding sex and reproductive health. Formal degrees must then lead to decent jobs and other opportunities.

Young people, moreover, deserve more say in politics. This planet is the only one they will ever have. Not only in Germany, we see a pattern of climate policy being slowed down whenever budgets are tight and decision-making becomes difficult. Everywhere on earth, this is casting a very dark shadow over young people’s future.

Katharina Wilhelm Otieno belongs to the editorial team of D+C/E+Z.

euz.editor@dandc.eu