Social media

Hate speech unchecked

In the recording, a voice is heard calling for the mobilisation of youth, with violence if necessary, to stop a certain community from registering as voters in the politician’s constituency. The voice is similar to the one of Aden Duale, the leader of the majority in Kenya’s parliament.

In mid-February, the authenticity of the recording had not been verified, and Duale denied responsibility for the inflammatory remarks. According to him, the audio was fabricated by “political enemies”.

In Kenya, hate speech remains largely unchecked during election campaigns. It is well understood, however, that it often precedes violence. Aggressive rhetoric is common at public rallies and political meetings, and sometimes it is contained in song lyrics.

According to observers like Willy Mutunga, Kenya’s former chief justice, the country is at a dangerous precipice. Mutunga has warned of “drumbeats of possible violence in the next elections,” referring to “signs of politicians inciting people along ethnic lines”.

In a similar vein, civil-society activists have noticed simmering undercurrents of provocation and incitement. They argue that the current political atmosphere is similar to what preceded the post-election violence in 2007/08, when up to 1,300 people were killed and more than 600,000 displaced (see comment).

Hate speech is expected to increase as the hunt for votes intensifies. Political rivals openly refer to each other as “enemies”. They attack each other openly, stoking emotions and animosity among their supporters. Some politicians from the two main political camps – the ruling Jubilee Party led by President Uhuru Kenyatta and the CORD coalition led by opposition leader Raila Odinga – are outspoken and engage in hate speech openly.

Moses Kuria, who belongs to Jubilee, has called for the assassination of Odinga, for instance. On the other hand, Millie Odhiambo of CORD caused a stir when he insulted Kenyatta. “Who does he think he is, he does not even compare to me, leave alone Raila Odinga, tell him he can take me to court,” Odhiambo said, “he is extremely stupid and my conscience tells me so.”

Impunity is the norm. Legislation has not effectively stemmed hate speech. Only one case has been successfully prosecuted. A university student was sentenced to two years in prison for insulting the president on the social media site Facebook, but he was soon released.

The government has cautioned politicians, their supporters and media owners against misusing digital platforms to stoke ethnic tensions in the upcoming elections. However, its action to de-escalate the situation remains half-hearted.

In a highly sensational first episode of its kind, eight politicians from both CORD and the Jubilee Party were arrested in mid-June 2016. They were accused of alleged hate speech and incitement to violence. The lawmakers spent a night behind bars. Upon release they made a short-lived pledge to “travel the country on a peace caravan to preach peace and conciliation”. That commitment never materialised, however.

Anti-social use of social media

Facebook and Twitter are proving to be fertile ground for hate speech expressing tribal stereotyping and contempt. Kenya’s Communication Authority estimates that 85 % of the citizens have internet access and mostly use social media. On Twitter, Kenya is the fourth most active African country, according to the PR company Portland Communications.

Ordinary Kenyans launch vitriolic attacks relating to the issues of the day and reflecting political loyalties. They deride each other with ethno-insults, some of which are extreme. Arrests and prosecutions are rare, and perpetrators seem to know that legislation is weak. They take full advantage of loopholes.

Kenya’s police accuse the courts of not punishing those who are responsible for hate speech. Stringent sentencing could indeed serve as a deterrent. The National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC), moreover, seems to be incompetent and overburdened. Its duties include dealing with hate speech, but its budget is tight.

Kenyan media houses must bear some of the blame for perpetrating hate speech. Especially in an election year, their appetite for sensational political stories on prime time news is not helpful. Vernacular radio stations, moreover, are known to broadcast coded messages against other communities. Social media sites also use vernacular languages for doing so.

The NCIC has recently launched investigations of a local vernacular FM station associated with President Kenyatta. A voter registration advertisement had stirred controversy. In the 90-seconds recording, the presenter urges the Kikuyu community to come out in large numbers to defend their “throne”. Kenyatta belongs to the Kikuyu community, and he is the forth president to do so.

What needs to be done

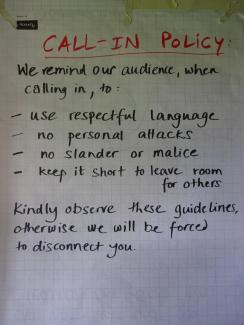

Victor Bwire of the Media Council of Kenya, a self-regulatory statutory body, says matters should improve: “The indiscipline of vernacular radio and TV stations must be dealt with without fear or favour.” In his eyes, the relevance of political contributors must be vetted in regard to whatever topic is being discussed, but ethnic identity as such should not be considered important.

Experts agree that it will take sustained efforts to deal with hate speech. Law-enforcement agencies, civil-society organisations, religious establishments and traditional leaders all have a role to play. Success will depend on coherent action and cooperation.

Shitemi Khamadi, a prominent blogger, has made some suggestions. He does not want the media to rebroadcast statements when politicians have used hate speech. The reason is that such rebroadcasts are divisive. Moreover, the media should insist on politicians clarifying dubious statements. Finally, Khamadi wants the media to deny airtime to political leaders known for fanning ethnic tensions and using hate speech.

The Communication Authority of Kenya says it is investing $ 19 million to acquire equipment to monitor online and offline communications during the election campaign. It is to be hoped that it will use the equipment well. The country’s peace may depend on it.

Isaac Sagala is a journalist and media trainer. He lives in Nairobi.

bwanasagala@gmail.com