Climate activism

“The climate movement is much less naive now”

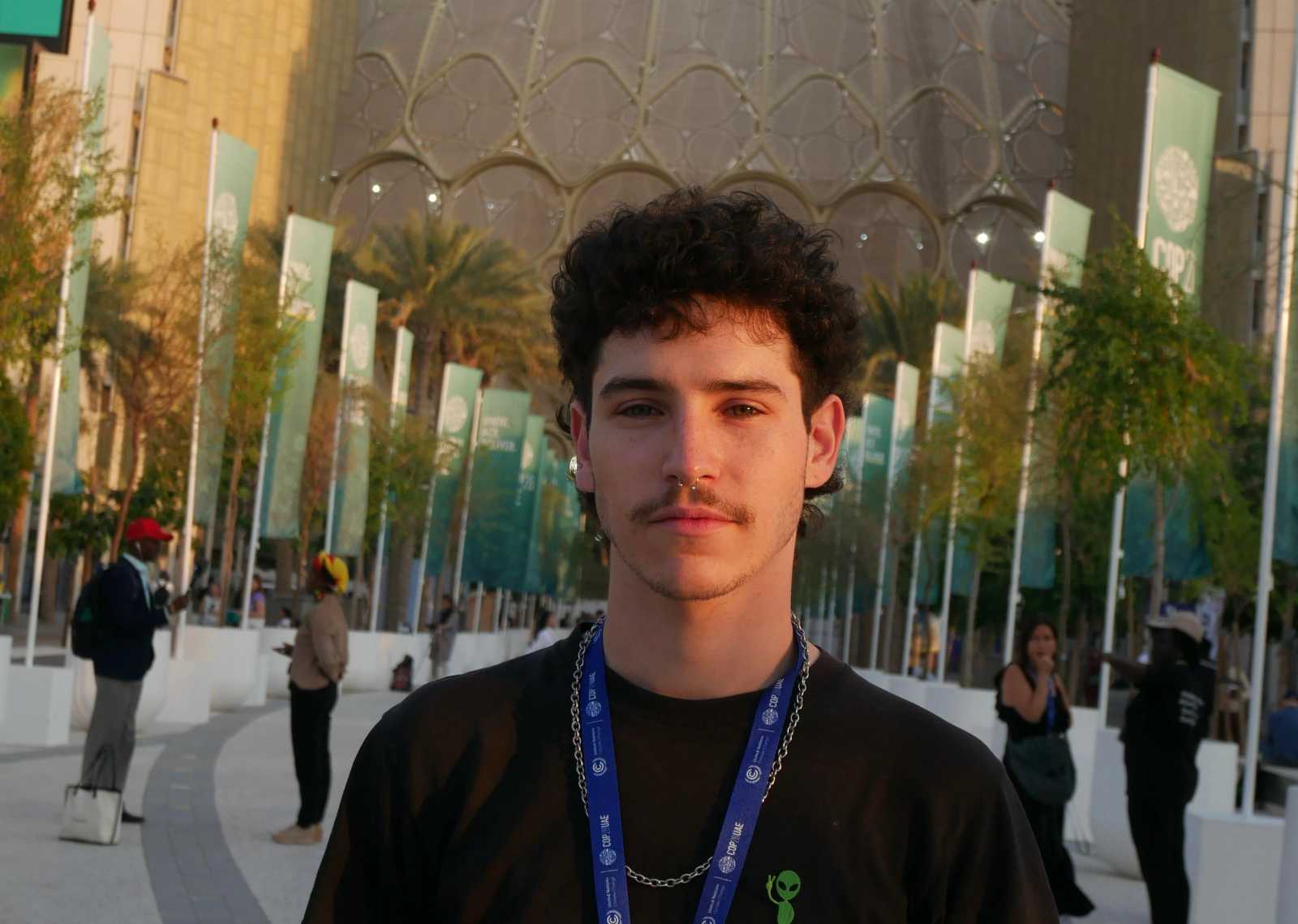

Linus Steinmetz in an interview with Jörg Döbereiner

International headlines in recent months have been dominated by the conflicts in the Middle East, Kashmir and Ukraine. Multiple column inches and minutes of airtime have also been devoted to US President Donald Trump’s tariffs policy and the election of the new pope, Leo XIV. During the German federal election campaign, migration and the economic situation in Germany were the key issues. Is enough media and political attention currently being paid to the climate crisis?

No, despite this being the central crisis we are facing in the 21st century. It affects countless areas. Why is Donald Trump suddenly staking a claim to Greenland? Naturally he is keen to get his hands on the resources there, but he is also counting on the polar ice melting – factoring climate change into his plans, in other words. International politics and climate change are inextricably linked these days.

Furthermore, surveys show that many people in Germany and elsewhere are still taking the climate crisis very seriously. They are worried about the climate and their future. And yet the climate crisis is much less prominent in media reporting than one would expect.

What is the reason for this?

For one thing, the climate crisis is a difficult story to tell by comparison with other topics. Many people take a very acute view of it as a major problem but still see it as an unsettling background issue that is difficult to really get their heads around. Other urgent crises around the world are more tangible and easier to report on. What is more, it is clear that the necessary structures have not yet been sufficiently established: Media, movements and political parties still have their work cut out to build dedicated climate reporting capacity. Foreign correspondents have a much higher profile than climate correspondents – when indeed the latter exist at all. This may also be a generational problem: Many young journalists would like to write more about the climate crisis but find themselves having to report about energy or international policy. At least there is no lack of stories to tell, as the impacts of the climate crisis can be found everywhere.

What is the current mood in the climate action community?

There are various emotions, one being a sense of disillusionment. We no longer talk as much about stepping up our climate action ambitions, for example at the major climate conferences or at EU level. Instead, it’s more about how we can ensure that at least a minimum degree of climate policy is enacted. And we don’t exactly have the feeling that we are winning this battle just now. At the same time, many people take a pragmatic and, in some cases, optimistic view of the future. We know that the problem won’t go away. In Germany, the climate movement will be keeping a very close eye on the coalition government. There were major political shifts last year, both in Germany and abroad, and now we have a clearer idea of where we stand. Obviously, it is depressing to see Donald Trump in the White House. But it’s also clear now whom we climate activists are struggling against: him and the other leaders whose policies are jeopardising our planet and our future on all kinds of levels. This results in a new clarity that is energising us.

The mood was rather different when Fridays for Future began to become popular in 2018.

We were euphoric, and many of us thought it was just the beginning of something that would go on and on. There were more of us every week, exerting pressure on politicians. It was embarrassing for politicians not to be on our side. And yet it has now become completely acceptable again to demand backpedalling on the climate. That’s partly why we are disillusioned, though we have also become more realistic. At COP25 in Madrid in 2019 for example, very many people sided with us and voiced their support for more ambitious goals. We know now which of them meant it seriously. The climate movement is much less naive now.

Just a few months after the conference in Madrid, the whole issue of the climate was overshadowed by the coronavirus pandemic. Studies show that climate reporting initially declined internationally but then picked up again around the climate summits in Glasgow in 2021 and Sharm el-Sheikh in 2022. Generally speaking, it is now at a higher level than before Fridays for Future was launched.

Our protests were certainly not in vain. On the contrary, the millions who took to the streets achieved an incredible amount. Many people around the world now acknowledge the problem, and as soon as the time is right will once again devote a great deal of their time and energy to combating the climate crisis – or indeed are already doing so. The major fossil-fuel companies and political actors such as Donald Trump may believe that they can continue to promote fossil energies far into the future, supported with loans from banks. In my view this is an overly complacent attitude, as it simply won’t make financial sense in the long run. That’s why, despite all the setbacks that we have definitely experienced, I remain optimistic. We will continue to make progress.

What needs to happen to focus more positive attention on climate action again?

One of our biggest problems in Germany was that we didn’t state clearly enough who is actively in favour of climate action and who is against it. We tried too hard to integrate everyone. But to communicate the climate crisis, it is essential to name and shame those who are causing it. I’m talking about large fossil-fuel companies which have no interest in climate action and do everything in their power to delay the transition. In recent years they have openly admitted that they do not take their own climate targets seriously.

Often it is specific events that cause people to focus their attention on the climate again: annual climate conferences, the publication of reports, large-scale climate protests or natural disasters. How significant are such events?

They continue to play an important role. People need to experience time and again that they can take action against the climate crisis at the local level – be it by taking part in strikes and demonstrations or getting involved in clubs and associations. The worst thing we could do would be to say that the climate crisis is awful but that we don’t think we as individuals can do anything about it, so we will just step out of the limelight and get on with our lives. At the same time, it must be clear that these events alone are not enough. An expert report or a couple of successful lawsuits will not transform climate policy. What is required is a more fundamental shift and much larger majorities, which is why youth movements are needed again.

Is that an appeal to the next generation?

People would often appeal to me when I was 15, which is why I’m not keen now, as an adult, to make similar appeals to 15-year-olds. But yes, I do believe that a shift towards more real climate policy could be sparked again by creative democratic protests, by people taking to the streets. That’s why it is important to give the many people who have not yet taken to the streets various opportunities to get to know and learn from one another, for example at local weekday meetings. Sooner or later, such structures lead to genuine, rapid and sudden change, as was the case with Fridays for Future.

At the height of its popularity, Fridays for Future was mobilising huge numbers of people to take part in demonstrations. The next protest wave chose a different way to draw attention to itself: Representatives of Just Stop Oil in the UK or Die Letzte Generation in Germany blocked busy roads and airport runways. They poured tomato soup over paintings by Vincent van Gogh and daubed the stones at Stonehenge with orange paint. Though this made them the target of a great deal of criticism, it did not have the same mobilising effect as Fridays for Future did.

This kind of protest didn’t make people angry about bad climate policy but about the protests themselves. By contrast, Fridays for Future’s aim was not to provoke people but to galvanise them to take action against bad climate policy. One major problem is that this more radical approach to climate communication has made it easy for those who have no interest in climate action to discredit it. Nonetheless, the protesters’ intentions were not wrong per se, it’s just that they opted for the wrong means. That should serve as a lesson: It is essential to be aware of the impact one will have and how one will come across when demonstrating for a cause in public – after all, it can also backfire.

Linus Steinmetz is a climate activist who has also filed climate-related lawsuits. He studies political science at Freie Universität Berlin.

linus.steinmetz@climatestrike.net

This story is part of The 89 Percent Project, an initiative of the global journalism collaboration Covering Climate Now.