Masculinity

Sexualised violence against men: the Baby Reindeer effect

When he didn’t want to have sex with her, she mocked him and attacked his masculinity. “She thought that a man had to want sex and always be available,” says Max, whose name has been changed. When he tried to pull away, his ex-girlfriend called him a “wuss”. She knew the passwords to his social media profiles; every time they met, she would take his smartphone and comb through his messages and photos. Once she even slapped him in front of her parents. “I felt powerless, used and drained,” explains the student, who lives in Germany. He says he never thought of asking for help. He rarely talked about his relationship even with his friends.

Max says he was ashamed of letting himself be insulted and attacked. For a long time, he didn’t fully realise that he was experiencing relationship violence. He believed he was “emotionally dependent”. The psychologist Björn Süfke, who specialises in treating men, explains that these feelings are common. Cliches often distort survivors’ understanding of their own violent experiences. Media depictions and pop culture also shape a society’s ideas about sexualised violence – including what a typical “victim” looks like. “Men are perpetrators, women are victims,” says Süfke, summarising the common view.

It’s true that women are much more likely to experience stalking and relationship violence – all too often with deadly results. According to the United Nations, in 2023, a woman was murdered somewhere in the world approximately every ten minutes, usually by a partner, ex-partner or family member.

But boys and men experience sexualised violence, stalking and relationship violence too, at the hands of both men and women. There are still far too few narratives that reflect this reality and allow survivors to recognise themselves. One of them is the British series “Baby Reindeer”, released on Netflix in 2024, in which the Scottish comedian, actor and screenwriter Richard Gadd processes how he was stalked by a woman and sexually abused by a man.

More men are taking advantage of support services

In Great Britain last year, the series triggered a “Baby Reindeer” effect: After the show began streaming, significantly more young men turned to help centres for men affected by violence. “Baby Reindeer” also illustrates how difficult it is to set boundaries in intrusive relationships – because survivors had a good relationship with the person at first, they inaccurately assess risks, they have good experiences as well as bad, they’re afraid of the consequences or they don’t want to hurt the other person.

“The series is creative, and I think it’s good that the issue is receiving more attention in the media and pop culture,” says Max, who needed three years to free himself from his ex-girlfriend. “There should be more shows like it.” He doesn’t think that violent experiences always necessarily have to play the starring role, like in “Baby Reindeer”; it would also be helpful, in his opinion, if stalking or relationship violence against men featured in side plots or individual scenes in movies.

The Netflix series inspired many discussions and touched many people. “I felt completely exposed, like someone had dug out all my secrets, stripped me naked (…), and put me in the middle of a full stadium,” one user of the online platform Reddit said of his experience watching “Baby Reindeer” with friends. “If I were alone, I would have bawled my eyes out and curled up into a ball, but I just sat there and pretended it just slightly bothered me.” It was difficult for him to talk about his problems, admit things, truly open up. “Baby Reindeer”, he believes, influenced many men who share his experiences, in part because the main character, Donny, played by Richard Gadd, is not a “perfect victim”, but rather “a real life, imperfect human”.

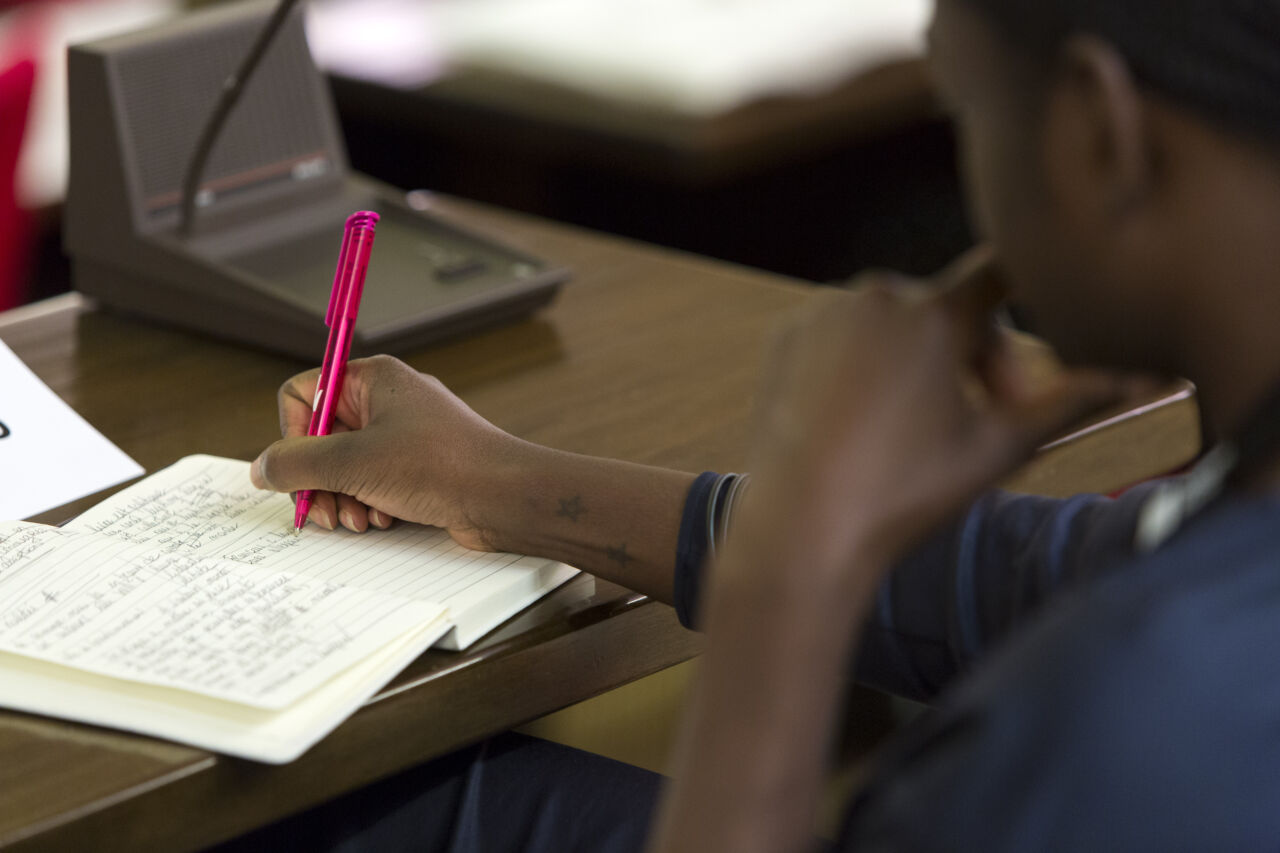

Talking about violent experiences

Counselling services or shelters specifically for men are rare worldwide, and many men are reluctant to seek help. The psychologist Björn Süfke, who helped establish the “Gewalt an Männern” (“Violence against men”) helpline in Germany, observes that because of traditional gender roles, men frequently have an even harder time than women talking about their experiences of violence. They also attend therapy far less often.

“Defining oneself as a victim and seeking help can feel like a blow to one’s masculinity,” says Süfke. “The biggest hurdle is admitting that.” But silence and loneliness can be life-threatening: The global suicide rate is significantly higher for men than for women. Low-threshold approaches like “walk and talk”, which replace traditional therapies with activities that do not require sustained eye contact, like taking a walk, are designed to alleviate men’s fears.

Breaking the silence

Some initiatives are also attempting to reach boys and men on social media or gaming platforms. For example, British activist Jeremy Indika raises awareness about child abuse on various social-media platforms as well as on podcasts. He wants to draw attention to the fact that many boys and girls experience sexualised violence without it necessarily being obvious. After all, it took a long time for anyone to notice that he himself had been abused by an older man when he was eight years old. “I was doing well in school. I had a strong circle of friends. I was outspoken in class and considered bold and forthcoming,” Indika writes on his website. “There was no way of telling what I had been experiencing. It was like I had buried it deep somewhere.”

At 25, Indika began to experience flashbacks; memories of the assaults were coming back. When he went online to look for other survivors, he realised that this was an enormous problem worldwide. Indika’s digital initiative, “Something to say”, offers a platform to people who were abused as children or adolescents. They show their faces as a way to break the silence surrounding child abuse.

The psychologist Elias Jessen is a PhD candidate who researches communication services for young men at Berlin’s Charité hospital. He advocates for devoting much more attention to digital campaigns in the online spaces where young men spend time. For example, Jessen thinks that serious topics could be addressed in a relaxed atmosphere on a gaming platform like Twitch. There and on platforms like TikTok and YouTube, as well as on his podcast, he discusses gaming and pop culture alongside issues like mental health, relationships and violence. His goal is to reach young men by addressing them in an approachable and authentic way without being too intellectual or serious.

Jessen reports that feedback has been positive. Some men have written that they now think differently about mental health. Some are even considering starting therapy.

Links

If you are a survivor of violence or sexual abuse, please make use of helplines in your country or region. You can find helplines in various world regions here:

https://findahelpline.com/

Jeremy Indika’s “Something to say” initiative

Sonja Peteranderl is a journalist and founder of BuzzingCities Lab, a think tank that focuses on digital innovation, security and organised crime.

euz.editor@dandc.eu