Terrorism

Look beyond private schools

Six young militants attacked a café in Dhaka and killed 20 hostages, including several Italian and Japanese citizens. The terrorists themselves were killed by the security forces, and two other persons died as well.

ISIS, the international terror outfit, claimed responsibility, but the government denies it is relevant in the country, insisting that local militants are the problem. Moreover, ministers have pointed out that perpetrators were educated at elite, private-sector institutions and demanded action against such institutions. The student organisation of the Awami League, the ruling party, has announced it will form committees in all private universities to keep a vigil and “fight militancy”.

To some extent, the focus on private education makes sense. It is disturbing that young men from privileged families, who can afford to pay for schools and universities that teach in English and adhere to international standards, have turned into violent extremists. Earlier perpetrators of fundamentalist violence also belonged to that social class, including, for example, the murderers of Ahmad Rajib Haidar in February 2013. Obviously, the sense of alienation can be very strong among elite youth. However, some of their Bengali victims were also privately-educated, which shows that society is deeply split.

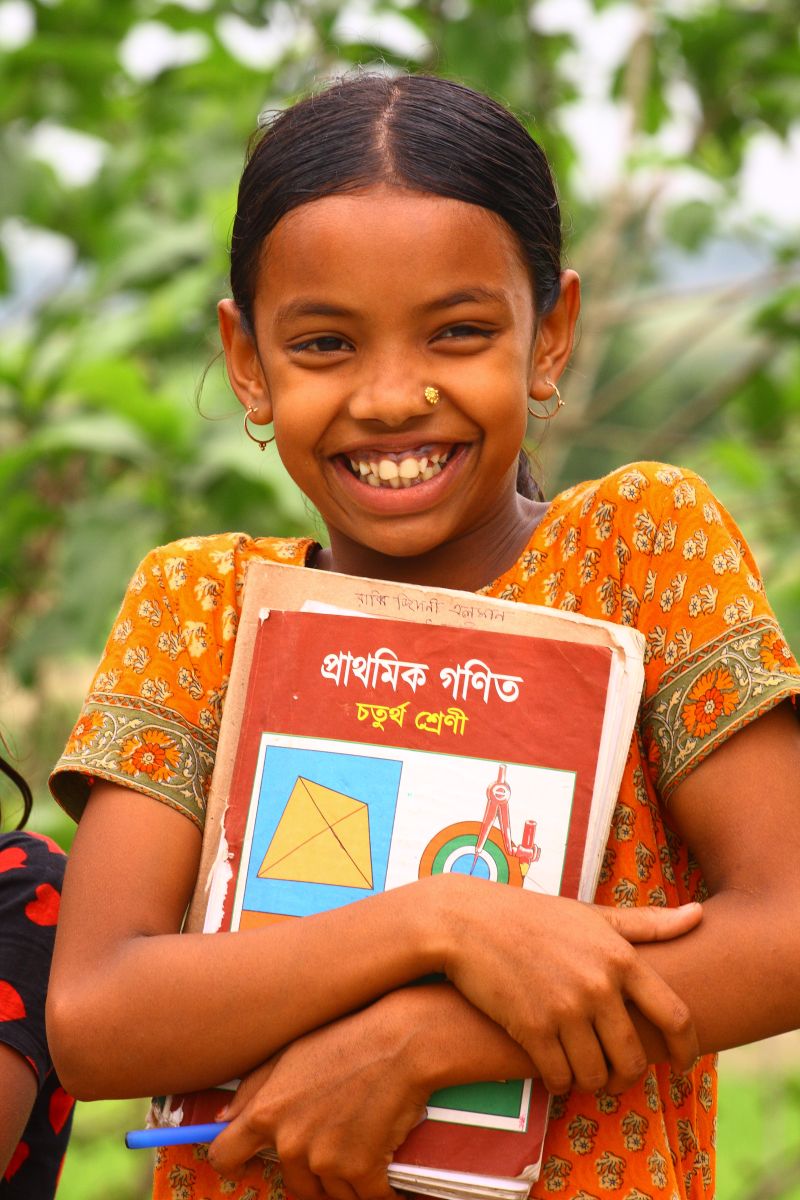

One must look beyond private education however. One reason it has expanded fast was that state-run education sector is sub-standard. Though Bangladesh’s public universities are heavily subsidised, not one of them features among Asia’s top 100 universities. Exam papers are frequently leaked. Students engage in rote learning and rely on private tuition instead of regular classroom teaching.

The pubic universities are known for corruption. Scholarship, moreover, is being undermined by violent politics, with the Awami League’s youth wing playing a particularly destructive role. Its leaders keep making headlines with murder, extortion, arson, sexual offences and other crimes. Its plans to provide vigilance on private campuses therefore sound quite threatening.

Not only the universities are miserable, however, schools are dysfunctional too, as I elaborated in a paper I co-wrote with Nazmul Chaudhury (2015). Millions of adolescents are in school, but not learning. The lack of effective literacy skills and the inability to think critically can make them vulnerable to radical and extremist ideology.

Despite many limitations, English medium schools have for decades served as a complement to government’s own educational initiatives. They must not be singled out as a security threat. Doing so would only create more divisions among Bangladeshi citizens.

The government must improve its schools. It must adopt and implement credible policies for that purpose. Moreover, it must improve governance in general and enforce the rule of law. All too often, lawmakers are found out to be law breakers themselves. Extremism is likely to thrive in a political environment where governance is bad and there is no sense of public accountability.

Private education is certainly not the core issue, but one must assess what its contribution to youth radicalisation is. Some experts and free-market enthusiasts promote private education as a matter of principle. The London-based magazine The Economist, for example, has enthusiastically stated: “Where governments are failing to provide youngsters with a decent education, the private sector is stepping in.” It is worth considering whether that is really always helpful in view of the atrocities in Dhaka. It matters even more, however, that its approach is obviously too expensive to provide millions of poor young Bangladeshis with the education they deserve.

M Niaz Asadullah is professor of development economics and deputy director of the Centre for Poverty and Development Studies (CPDS) at the University of Malaya.

m.niaz@um.edu.my

Reference:

Asadullah, M. N., and Chaudhury, N., 2015: The dissonance between schooling and learning. In: Comparative Education Review. Vol. 59(3), pages 447-472.