Migration

Death on the southern border

For several years, the EU has been boosting its measures and increasing its budgets to protect its borders. The justification is always the same: to make an effective and necessary contribution to the EU’s internal security.

Little has been done to protect the affected migrants however. The people who are targeted by the border regime have usually been in transit for years. They are often fleeing from civil war – like in Syria or Somalia. On their way, they risk kidnapping, robbery, jail and even murder. When they approach the EU, however, they face a comprehensive policing and security system.

There are huge fences along the Greek-Turkish and Bulgarian-Turkish borders, and fences around the Spanish exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in North Africa. But these physical barriers are only the most visible elements of a much broader strategy to keep migrants out. High-tech systems, developed by large European defence contractors, matter too. The European border patrol system EUROSUR, for example, gathers information on migrants’ movements in the Mediterranean region with drones, radar, satellites and aircraft.

Thanks to such information, armed patrols intercept migrant groups, either to save them from distress or to conduct “push-back” operations that breach international law. There have been reports of life-threatening manoeuvres to push or drag migrants’ boats from their course from Europe’s territorial waters for example. Human-rights organisations have documented how, in the course of such operations in the Aegean, the Greek coast guard destroyed or heavily damaged refugee boats, with the result of passengers drowning. Refugees who survive such violent attempts to ward them off usually have no means to seek legal redress.

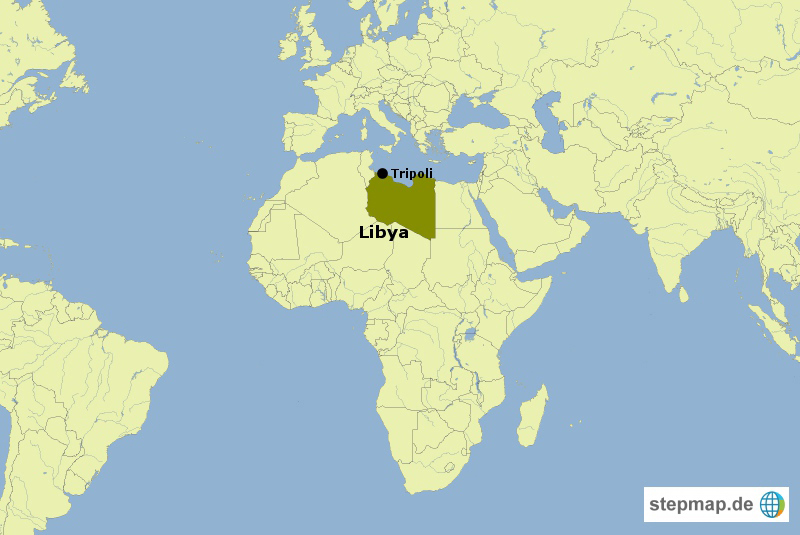

Beyond its external borders, the EU is trying to stop migration through a so-called “advanced deployment strategy”. It offers targeted support to border protection authorities in transit countries, for instance by training local security forces. This is something Germany’s Federal Police is doing in autocratic Belarus. Another option is to dispatch an official EU mission, for example into civil war-plagued Libya. At the same time, EU member states export weapons and security technology worth billions of dollars, primarily to North Africa. Algeria is producing some 1000 light wheeled tanks, particularly suited for border security, on the basis of German-made kits.

Fighting migration using any means

Coordinating and managing many measures to combat “irregular” migration is the job of Frontex, the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union. Frontex was founded in 2004, is based in Warsaw and has several hundred officers.

The agency has seen its mandate and budget grow fast in the past ten years. Annual funding by the EU member states will hit € 114 million in 2015, up from € 6 million in 2005. The responsibilities of Frontex include:

- intelligence,

- risk analysis,

- planning and coordinating of joint operations by EU members,

- education and training of border guards,

- support for mass deportations and

- the negotiation of cooperative projects with countries outside the EU.

Since 2007, Frontex can deploy a “rapid response team” if an EU member state requests support for local border protection. For the duration of the mission, Frontex staff have sovereign powers. During a mission, in 2010, gunfire is said to have stopped migrants from approaching the Greek-Turkish border.

Saving human lives – like those trapped on ships in distress at sea for example – seems to play only a subordinate role for Frontex. Between 2000 and 2013, about 27,000 people died trying to cross the sea and reach the EU. That is the estimate of a journalists’ network (“Migrants Files”). But suffering and death on Europe’s external borders only rarely gets much public attention.

There are occasional exceptions to this rule however. Two shipping disasters in October 2013 – one just off the coast of the Italian island of Lampedusa – took the lives of several hundred refugees in a single week. “Lampedusa” fast became a popular synonym for Europe’s failed policy for dealing with “irregular” migration across the Mediterranean Sea. Citizens across Europe were shocked. Pope Francis spoke of a “disgrace”.

The response of policy makers was “Mare Nostrum”, an operation run by the Italian navy. It rescued more than 100,000 refugees in the Mediterranean Sea between October 2013 and November 2014. But the Italian government ended this effort at the end of 2014 because other EU member states refused to contribute to the monthly costs of about € 10 million.

Since then, Frontex has been securing the EU’s maritime borders around Italy. With a monthly budget of € 2.9 million and 65 employees, its operation “Triton” covers the sea south of Sicily and Lampedusa and the other Pelagic Islands, as well as the waters off Calabria. Its operating area is much smaller than the one of Mare Nostrum was. Mare Nostrum went up to 15 miles off Libya’s coast. That country is a popular starting point for the often unseaworthy boats refugees use. In February 2015, as this essay was being finalised, there was yet another shipping disaster near Lampedusa. According to newspaper reports, at least 29 persons died – but several hundred may have perished.

New rule

In April 2014, the European Parliament adopted a provision that, as a rule, dangerous “push-back” operations should be avoided. However, Frontex was explicitly allowed to “escort” intercepted migrants to other countries if they are deemed unqualified for asylum.

Opinions on the new provision vary widely. Its proponents speak of an important step towards respecting human rights. But human-rights organisations argue that the new provision made legal the “push-back” procedure which was illegal previously.

Moreover, the new rules are not reflected in the reality of Frontex missions. Secretly filmed footage recently showed the Greek coast guard in action in the Aegean Sea. “Do not make a move, or I’ll kill you!” a border guard yelled towards a refugee boat. The top priority remains border surveillance and defence against “irregular” migration. Humanitarian motives do not count much in the Frontex context. The shift in policy is problematic, especially because the number of refugees dying while attempting to cross Europe’s external borders is increasing from year to year. According to the UNHCR, more than 3,400 refugees drowned in the Mediterranean Sea in 2014, more than in any previous year. However, experts from the inter-governmental International Organisation for Migration suggest that the actual number of victims is probably much higher. They think that the bodies found represent only one third of all deaths by drowning.

Some say that the Italian navy’s rescue mission has made things worse. In this view, Mare Nostrum encouraged more migrants to try to cross the supposedly safe Mediterranean. But the real reason for the growing number of boat trips is probably that the EU has successfully sealed migrants’ traditional land routes at a time when the number of refugees is rising in general. Accordingly, more and more people are forced to take to the dangerous sea. Many of them die – not in spite of the EU’s measures to improve security on its external borders, but because of them.

The real scandal is that the EU and its members view refugees and migrants primarily as a security issue, which can be dealt with using technical – and often also violent – countermeasures. Thousands of people lose their lives at the EU’s external borders every year. Many of them die in what is one of the world’s most monitored seas. But their fate is of secondary importance, or, worse still, simply accepted as a matter of course. Unless there is a fundamental re-think this year, we must expect that 2015 will see yet another record annual death toll.

Marc von Boemcken is a researcher at the Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC).

boemcken@bicc.de

Ruth Vollmer is also a researcher at the Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC).

vollmer@bicc.de

Links:

International Organisation for Migration: Fatal journeys.

http://publications.iom.int/bookstore/free/FatalJourneys_CountingtheUncounted.pdf

Migrants Files: Database on more than 27,000 migrants who died on their way to Europe.

https://www.detective.io/detective/the-migrants-files

UNHCR: Global refugee numbers.

http://www.unhcr.org/53a155bc6.html

Death in the Mediterranean Sea:

http://www.unhcr.org/531990199.pdf