Political jargon

Why “global south” is not a useful term

It has become common to speak of the global south as though it were a homogenous group of nations. The idea is to distinguish these countries from high-income countries. For several reasons, I think the term is misleading.

First of all, the countries that belong to the global south are extremely diverse. China and Malawi do not have much in common. Nor do Brazil and the Fiji Islands, or India and Haiti. Small island states and least-developed countries are very different not only from China, the world’s second most powerful country, but other big emerging markets as well.

The governments of China, Brazil and India would like everyone to believe that they cooperate with the latter group in a spirit of unlimited postcolonial solidarity. But it is not the case. The full truth is that they even view one another with suspicions.

The second-most powerful country

China is the second-most powerful country on earth. Which low-income country would fly spy balloons across North America? Is China’s growing military prowess serving the global south? Well, Southeast Asian governments are certainly not happy about Beijing’s jingoistic claims to the entire South China Sea. China’s saber rattling makes people uncomfortable, not least because an attack on Taiwan cannot be ruled out.

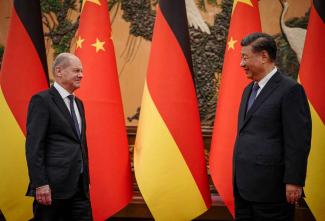

Whether China provides Russia with weapons or not, may yet prove decisive in the Ukraine war. Annalena Baerbock, Germany’s foreign minister, was proud to announce during a recent trip to Beijing that her counterparts told her China would not do so. Chancellor Olaf Scholz was similarly delighted when, during a state visit of his, China’s President Xi Jinping declared that the use of nuclear weapons remains unacceptable, including in Ukraine. No other country in Asia, Africa or Latin America wields similar influence.

China has become an important creditor nation

Beijing is playing an increasingly assertive role in other international contexts too. Its manufacturing industries are highly competitive, so the nation exports more goods than any other. China’s developmental success was spectacular from the early 1980s on. Hundreds of millions of people have been lifted from desperate poverty. The average per-capita income is now $ 12.600 – only $ 600 below the World Bank definition’s threshold for high-income status. This achievement deserves to be admired – but sets China far apart from low-income countries.

There are tangible consequences. For example, China has huge foreign-exchange reserves, while many low and middle income countries are struggling with excessive debt burdens. Indeed, a large share of their loans was handed out by institutions based in the People’s Republic. Progress on debt restructuring is very slow, and an important reason is that China fears that restructuring would put it at a disadvantage.

China’s approach to sovereign debt problems differs from western governments’ approach. Beijing is generally unwilling to forgive loans, but generous in regard to extending them. Moreover, it neither insists on measures to improve the macroeconomic situation nor coordinates its steps with other creditors. In other words, it has been unwilling to learn from the experience of western donor governments in debt crises of the past.

According to China’s leaders, governments always represent a sovereign nation and there must be no interference in internal affairs. Things are not that simple. Consider the case of over-indebted Sri Lanka. To what extent did the Rajapaksa clan that accumulated the debt serve the nation? Why did a popular uprising force them out? Who is responsible for cleaning up the mess?

These matters are tricky. Insisting that the formal government is always right does not help to sort them out. Western governments’ focus on governance issues in the context of development affairs is not simply a symptom of arrogance. It results from the experience that formal governments are often corrupt. The plain truth is that China has become an important creditor nation, and its government’s decisions determine the fate of people in low-income countries.

A century of humiliation

In the eyes of China’s leaders, their country suffered a century of humiliation by colonial powers from the mid-19th to mid-20th century. They see it slowly claiming its rightful place of leadership in the global order again. However, China’s regime does not take into account two important things:

- Claiming a role of global leadership is not compatible with eyelevel solidarity among former colonies.

- Unlike most other countries, China has had an uninterrupted understanding of statehood for about 3000 years. By contrast, the borders of most developing countries were arbitrarily drawn by the colonial powers.

China’s development in recent decades has been spectacular – and spectacularly different from what happened in other countries that were exploited in the colonial era. For many decades, China’s dictatorial regime was a developmental regime, and to some extent, it may still be one. Typical dictators exploit their countries, with leaders getting rich and the people staying poor. In China, by contrast, extreme poverty largely disappeared, while education and employment opportunities increased. In some areas, China’s infrastructure is now arguably the best in the world. No other country, for example, has a high-speed railway network of remotely comparable size.

Western observers are right to criticise China’s human-rights abuses, but there is no denying that the Chinese regime has an understanding of the common good, is trying to promote it and not only entrenching its power. That cannot be said of most dictatorships. Unfortunately, moreover, many formal democracies are dysfunctional. Corruption, cronyism and identity politics have kept many countries poor.

Corruption matters everywhere, of course. China is no exception. It is known that its top leaders store huge fortunes in western countries. That they have not ruined the country does not mean they are beyond blame.

Less than perfect multilateral partner

The regime in Beijing likes to pretend that it is setting an example of being a partner in multilateral settings. Its track record tells a somewhat different story. Had China been forthcoming with Covid-19 information in late 2019, the World Health Organization would have had a much better chance of preventing the global pandemic.

As for global heating, no country emits more CO2 than China. It’s annual per-capita carbon footprint is 7.4 tons. That is smaller than Germany’s (9.4 tons) but bigger than those of G7 members Italy (5.9), Britain (5.6) and France (5.1).

China clearly belongs in a category of its own. It plays a special role in global affairs. The usage of the term global south makes this special role invisible. China is definitely challenging western hegemony, but it is not doing so on behalf of each and every former colony. Its regime is consistently pursuing what it considers to be the national interest – which, obviously, coincides with its own interests.

PS: By the way, the dichotomy global south and global north does not even make sense geographically. Australia, New Zealand and Chile are three of the southern-most countries, but belong to the OECD, the club of prosperous nations. Argentina is an upper-middle income country. Russia, by contrast, spans half the Arctic circle and is a former colonial power, but somehow does not belong to the global north.

Hans Dembowski is editor-in-chief of D+C/E+Z.

euz.editor@dandc.eu