Interview

Transparency is feasible

A member of Indonesia’s ruling Democratic Party accuses you of not having any proof for your claim of corruption risks in his country’s defence sector being in the “very high” category. He adds that he considers your approach “tyrannical”. What is your take?

Our report is not based on opinions, nor does it gauge governments’ perceptions and assessments of corruption risks. Our results are based on 77 technical questions. Our researchers interviewed people from ministries, think tanks and universities to learn what mechanisms are in place to prevent corruption in the sector. To avoid errors, we did our best to standardise the answers and make them comparable. In the process, every government was twice given the opportunity to comment on our work. Indonesia refrained from doing so. We want to cooperate with governments in a cooperative way. Our index is meant to show them what they can improve.

How did other countries react?

Quite a few countries were similarly surprised by our findings – Venezuela and the Philippines for example. Others only learned about the risks in their country through our work. In our eyes, the best result of our publication is when governments discuss the entire paper with our offices in their countries.

Never before has such a vast amount of data been published on a policy area that is normally kept secret.

Yes, indeed. Throughout history, security and defence issues were always guarded from the public. Our idea was to provide transparency by making accessible to the public the knowledge we gained in two years of research. This is the best contribution we can make.

How does one measure susceptibility to corruption?

There are five core areas of risk: politics, finance, personnel, operations and procurement. The corruption risks of military operations and peace missions are quite high. Of course, the abuse of funds does not only put the people on the ground in danger, it may thwart success altogether. We identified 29 corruption risks and drafted our questionnaire on that basis. After the interviews, two other researchers checked the results and forwarded the first draft to the governments for comments. Later we compiled everything and sent the governments the final version. If they wanted to, they were welcome to express their views on our website.

What are the most important results?

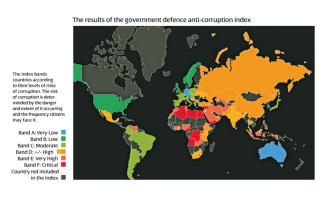

Well, 70 % of nations can only insufficiently protect their security and defence sectors from corruption. Among them are 20 of the 30 biggest arms importers as well as 16 of the biggest 30 arms exporters. Only in two nations – Australia and Germany – is the defence sector really well controlled. There are far too few anti-corruption mechanisms that rely on transparency and accountability. Only 50 % of the nations surveyed rely on transparent procurement procedures. Moreover, 41 nations publish no, or only limited information on defence spending. The citizens do not know what happens with their tax money.

What were the main challenges you faced?

There were two, one was not enough information, and the other was to make the information and scoring consistent across all the nations:

- In countries that do not provide information on their defence sector – such as Nigeria, Egypt or Yemen – our researchers struggled to access the information they needed to answer our questions as best as they could. Therefore, we mostly relied on researchers from the countries proper, because they understand their nation well.

- After two years of research, however, the greatest challenge was to make the data from 82 nations comparable.

In Algeria, the corruption risks are “very high”, according to your index, particularly in regard to finance and operations. What does that mean for the Algerian people?

Well, they have no chance whatsoever of getting information on their government’s operations, spending or strategy. Everything is strictly kept secret, so the citizens have no influence. They do not know what the political leaders are doing and what impact that may have on their lives. There is no transparency and, accordingly, no trust.

Do high corruption risks add up to real danger?

Yes, I consider them a threat to national security. Corruption blocks a nation’s development. It puts people’s lives at risk, and leads to waste worth billions of dollars or euros. Corruption has deep roots, moreover, especially in the defence sector. Corruption risks are highest wherever governments shroud defence affairs in secrecy. That is where the risks set in. You won’t be able to tackle the issue without transparency and control.

The corruption risk is high during military operations, but only six of 82 nations have control mechanisms to check such risks. Can there be transparency in conflict regions and fragile states at all?

Yes, transparency is feasible. Colombia has seen armed conflict involve its military and guerrilla for 40 years, and nonetheless, this country has made good progress in fighting corruption. Today, Colombia is in the category of “moderate” corruption risks, according to our index. Things have similarly improved quite a bit in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia and Mozambique. The reason is that security and defence issues matter very much in these countries’ politics, and leaders have understood that corruption undermines their authority to decide things and govern, so they want to control the risks.

Can there be such a thing as transparency of secret missions?

Well, Australia and Germany, the only two countries with low corruption risks, are showing the way. They ensure secrecy by relying on multi-party parliamentary committees that monitor secret missions and must keep the secrets themselves. That is a way to provide transparency and keep secrets at the same time. Both countries, moreover, only spend one or two percent of their defence budgets on secret missions. Many countries publish data on their budgets. Some have internet platforms that update information on military affairs every week. These things are not secret.

Whistle blowers und journalists play crucial roles in revealing corruption, but they run risks for their lives.

Yes, that is true, and our survey showed how very, very poor defence ministries are at protecting whistle blowers. Only 10 % of the nations surveyed have set up mechanisms to protect informants. Our research shows that whistle blowers and journalists deserve much more support. A lot needs to be done in this regard.

How will you proceed from here?

We intend to publish the index every two years. It would be too much work to do so annually, and things do not change much in that short time. Moreover, we want to assess more countries. The 82 nations chosen in 2011 accounted for 94 % or $ 1.6 trillion of global military spending that year. Other countries have asked us why we did not assess them, and we’ll be happy to accept their invitation.

Mark Pyman directs the International Defence and Security Programme of Transparency International UK.

mark.pyman@transparency.org.uk

http://government.defenceindex.org/