Ecological destruction

Conquest by chainsaw

The dust is everywhere. Yellow, fine, dry particles swirl about in the hot wind before they are deposited on branches and leaves. In summer, it is 48 degrees in the shade. Gnarled old trees and thorny bushes make a tough thicket. Only few trails lead through this primeval forest. They belong to poisonous snakes and scorpions; human beings rarely come here. This is one of the last areas on earth not yet conquered by western civilisation: El Gran Chaco – the Great Chaco, the border region between Argentina, Paraguay and Bolivia. Half of it is in Northern Argentina.

After the Amazon, the Chaco is the biggest forest of South America. Its biodiversity is huge. There are cacti and carob trees, poisonous snakes, tapirs and yacarés (a kind of caiman), ant eaters, Ñandus (the ostrichs of South America) and pumas of course.

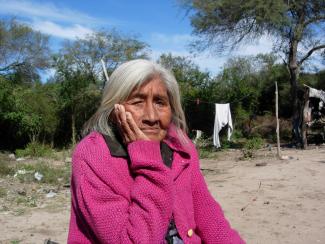

“When I was young, our whole family would travel to where we would find wild game. That was our food,” says Valerio Alejo, a Wichí Indian. “We used to hunt with Boleadoras, hunting balls, or with bows and arrows. Money did not even exist.”

Alejo is 62 years old today. He remembers the times when there was not even a provincial government. In those days, the word “Indians” was written over some regions on maps of Argentina – that was the territory that had not been conquered yet. The appropriation by the whites did not happen long ago. Alejo remembers: “They chased us. The old people tell how they hunted us with dogs, as if we were animals. But they did not dare to come into the forest, because if they did, our people would kill them.”

The forest was the last refuge for aboriginal people. Three and a half million hectares in the Chaco province are called El Impenetrable by the Indians, the Impenetrable. A primeval thicket of immense trees and thorns, and the home to four indigenous peoples: The Toba – who call themselves Qom –, the Wichí, Piligá and Moqoit.

Violent colonisation

El Impenetrable is the largest subtropical dry broadleaf forest of the earth. It is fiercely fought over by soy and cotton farmers who want to cut the trees in order to expand cultivation. The Chaco forest is being cut down six times faster than the Amazon jungle. The greatest profiteers are logging companies. Some 500 kinds of valuable hardwood grow here.

Lately, however, soy cultivation in particular has accelerated deforestation. In 1996, the corporation Monsanto introduced genetically modified soy beans in Argentina. Today, they are grown in huge quantities for export and animal fodder, and 95 % of the Argentine soy cultivation is affected. This country produces about half of the soy flour that is consumed globally, as well as soy oil for biofuel production. The provincial government of the Chaco has exempted soy producers from taxes in order to “promote industrialisation”.

The soy plantations not only eliminate the forest, but also other types of agriculture as well. ”Argentina has the highest per-capita production of food worldwide, around 3500 kilogrammes per year”, writes journalist Marie-Monique Robin. ”The agrobusiness operates with systematic violence against rural communities and indigenous people. Moreover, the intense use of fertilisers and pesticides poisons the water local communities depend on.”

The indigenous peoples are dislodged from their land, for instance the Toba. They are forest nomads who live by hunting tapirs and deers, as well as collecting wild plants. Many of them have only been in contact with white people since in 1970s. Most of the women do not speak Spanish. These people call themselves “Qom”. Approximately 22,000 of them are left. Since the land they used collectively is gradually being converted into private property, they are finding it more and more difficult to stick to their traditional way of life. Instead of woods, endless soy fields now expand to the horizon. Tapirs or ostriches can no longer be found. Hunting has become illegal and is punished with jail. Hunger is spreading among the indigenous people.

They have begun to try to protect their land against timber and soy companies by demanding that it be registered as commons. That is a difficult thing to obtain, says Victor Gómez, a 48-year-old Toba Indian: “The government plays rough, we have to keep on protesting and demanding so that we really get to keep our land. It is a never-ending fight.”

As most other Toba, Gómez grows vegetables and cotton, and raises a few chicken and goats. However, the indigenous people tend to have hardly enough land even for agriculture. The land is usurped by whites, because it is not fenced in.

The non-governmental organisation INCUPO (Instituto de Cultura Popular), which is supported by Misereor, a German faith-based aid agency, has started several projects in the Chaco. One of them concerns building fences, so the Indios can use the few hectares which are left to them in peace.

Since 2007, there is a law which is supposed to regulate and control the cutting of timber in the Gran Chaco, but illegal logging continues. It has actually increased, according to the organisation REDAF (Red Agroforestal Chaco), a non-governmental network of environmentalist groups of the province. According to Fundación Avina, on average, 1130 hectares are cut down per day – this equals 2300 football fields.

REDAF is aware of another danger. The government of the Chaco province is drafting legislation to allow forest clearance in search of oil. According to national and international standards, the indigenous people must be asked for permission first. Nonetheless, there are no public hearings on issues like this. Several infrastructure projects are supposed to materialise by 2015, including roads, gas pipelines and even nuclear plants.

Subterranean water reservoirs

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are campaigning against the destruction of the Gran Chaco. According to ENDEPA, a national organisation of indigenous people, deforestation is not even mainly about timber: “The Indios in Argentina are facing multinational corporations which are massively buying real estate, in Patagonia as well as in the Chaco. Many of these companies are bogus firms with addresses in tax havens. As far as we understand the motives of these companies, they are interested in the natural resources of this country. We are seriously concerned, because great water reserves – above and below the surface – are coming under the control of these corporations.”

Under the dry, thorny forest, there is a huge subterranean water reservoir: a part of the Gran Chaco belongs to the Guaraní aquifer, which also passes below Brasil, Paraguay and Bolivia. It is assumed that this aquifer is the second biggest freshwater reserve of the world.

Acuífero Guaraní

An aquifer is an underground water-bearing bed. This kind of geological formation contains fresh water, sometimes very deep in the ground. The biggest fresh water reserve of the planet is the perpetual ice of the arctic and antarctic. The second biggest reserve is probably the Guaraní aquifer. Its water resources are in the Gran Chaco, aboveground and belowground. The aquifer passes under several countries. The Acuífero Guaraní is so vast that its limits have not been determined yet. Apparently, it stretches from the Gran Chaco east to the Iguazú water falls and continues under Southern Brasil, where mega-cities, in particular São Paulo, depend on ground water. In Argentina, the aquifer spreads south, under the wide grasslands of the pampa, and then feeds the ramified river system of the Paraná. Apparently it stretches even further, to the perpetual ice of Patagonia, the southern tip of Argentina. The aquifer makes Argentina attractive to long-term water speculators. Extensive land grabbing around the Patagonian lakes by foreign companies, as well as in the Gran Chaco, are considered evidence by local NGOs.

Indigenous resistance

Since 2008, many indigenous people are organised in the “Movimiento Nacional Campesino Indígena” (National Movement of Indigenous Peasants). Carlos Rubén is one of them. He is a Wichí; his Indian name is Chupí. In his mid-thirties, he is going to night school today. As many kids of his tribe do, he had dropped out of school as a child. He resented the fact that the school was separated along race lines. It was strictly forbidden to speak Wichí. “Back then, total racism ruled”. he recalls. “There were even different drinking cups for Indian and white children. This is not so anymore. But we still don’t know enough about our rights. This is why the whites can still treat us as they please.”

Once a month, a lawyer visits the Wichí. Pedro Fabián Troncoso is a legal advisor with ENDEPA. He resolves territorial disputes for the Wichí, and he organises workshops on legal issues. Whole villages gather under big trees when the lawyer explains how to file complaints with the police when strangers poach in their reservation, or how the Wichí can obtain land tenure.

Troncoso accuses the government of not enforcing environmental laws: “The province has radars connected to computers, so it can monitor whether tress are being cut down. But nobody cares – neither the forest authority nor the transport authority, which could confiscate the trucks with illegal timber.”

The politicians try to calm the indigenous people down. Several political parties promise favours and social assistance to Indio leaders. But most don’t cave in to bribes. 60,000 families in the northeastern Chaco continue to fight for their land. They want to live their life in harmony with nature, as they always did.

Julio César Bernio is teacher for bilingual and intercultural education in the Chaco province, Argentina.

juliobernio@yahoo.com.ar