Faith

Deadly pro-life rhetoric

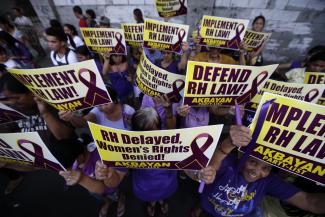

The Catholic Church suffered a stinging defeat last December when President Benigno Aquino signed a law giving free, non-compulsory family planning services to Filipinos. The RH law (Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act of 2012) guarantees universal access to sex education, contraception and maternal care. Basically, the law makes sure that women can decide for themselves whether they want to prevent pregnancies or not. It does not legalise abortion.

The act was debated for over a decade because of uncompromising Church opposition. Last year, Aquino seriously pushed the matter, and an acrimonious public debate ensued. It energised a broad-based movement for maternal health and family planning as well as women’s and gay rights. The movement includes secularists and freethinkers, but also many Catholics. Former health secretary Alberto Romualdez recently told journalists that some bishops actually favour the law but are just keeping quiet.

Acrimony

Most bishops and their “katoliko-sarado” (“closed Catholic” or blindly obedient) supporters have certainly not done themselves any favour by describing RH advocates as “abortionists”, “pro-death”, “Satanists”, “murderers”, “atheists” and “subversives”. Last year, some priests demanded during mass that RH supporters get up and leave. Some walked out and tweeted about it. Archbishop Ramon Arguelles even said President Aquino would be killing “millions of children”, comparing him to the American mass murderer who shot 20 schoolchildren last year.

To hardcore Catholics the RH Act will allow a cascade of horrors to follow. Joselito Asis, the secretary general of the CBCP (Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines), sums up the threats with the acronym DEATHS for “divorce, euthanasia, abortion, total reproductive health, homosexuality, gay marriage and sex education”.

The pro-life rhetoric rings hollow to RH proponents. They argue that the use of condoms would help to stem the spread of HIV/AIDS. They also point out that many women die from illegal abortions. Contraception could prevent much suffering – and that is especially obvious in view of the Philippines’ fast population growth, which is set to exacerbate poverty. The Church’s obsession with intimate matters looks bizarre given its series of international sex scandals.

In the big propaganda battle of 2012, the CBCP seemed out of touch. It came across as paternalistic, interested only in maintaining dogma and exacting obedience from the faithful, with no concern for women’s rights or people’s empowerment.

In the end, Aquino succeeded in pushing through the law. Forced to choose between the president’s will and the bishops’ ire, a majority of congressmen voted for the bill. Unlike previous presidents, Aquino didn’t flinch from confronting the Church. The bishops were particularly galled because the person to out-manoeuvre them was the son of the late Corazon Aquino, a former president who was so pious she is practically considered a saint.

Rather than pause to reflect on why it lost, the CBCP immediately doubled down like a gambler raising the stakes. Insisting that “contraception is corruption”, they told the faithful to protest. They also called for a “Catholic vote” in the combined national and local election to be held on 13 May in the hope of overturning the law (Editorial update 17 Mai 2013: Early results showed supporters of Präsident Aquino leading in both the Senate and House races).

The CBCP and its allies scored a minor victory in March when the Supreme Court unexpectedly blocked the law’s implementation. The Court will hear the case in June. Startled RH partisans suspect it is a religiously conservative ally of the CBCP.

Electoral politics

When this essay was written in mid-April, it remained to be seen how the election would play out. However, many Filipinos found it re-assuring that the Catholic vote has historically been a no-show even though their country is deeply marked by this faith (see box).

- In 2010 Aquino won the presidency with 15.2 million votes, whereas the Church-backed candidate for the same position got a mere 44,000.

- In 1998, the bishops lobbied against the drunkard womaniser Joseph Estrada’s run for the presidency. He won with a landslide.

- In 1992, Fidel Ramos, a Protestant, was elected president without the bishops’ endorsement.

At other political levels, candidates have also often prevailed against Church opposition. “There really is no Catholic vote in the Philippines,” says Edcel Lagman, a pro-RH congressman. In his eyes, the Church is weakening itself by “propagating its anachronistic dogma.”

The Church’s stance reduced the May elections to a single issue, which does not serve democracy. Indeed, the CBCP commanded the faithful to vote only for candidates who oppose the RH bill, even if they happen to be corrupt or unqualified. The bishops set aside all other issues, including social justice. As the newspaper columnist and former priest Orlando Carvajal pointed out, the Church was “in effect telling voters that artificial contraceptives are the country’s overarching problem.” He considers “prosperity for all” the more important moral imperative.

By endorsing specific candidates, the Church hierarchy meddled in politics in a way it is not supposed to. “The Church has always said, and this is the teaching, that it should not be involved in partisan politics,” says Father Jose Mario Francisco S. J., who heads the theology department at the prestigious, Jesuit-run Ateneo de Manila University.

This stance makes sense. Stringently applied, it would ensure that the church is not polluted by petty politics and can credibly comment on big issues. “To be effective,” Father Francisco says, “we need a church that is listening, that is humble”. It remains to be seen, whether new Pope Francis, who is a Jesuit like Father Francisco, will make a difference. His track-record on reproductive-health issues as Archbishop in Argentina is not promising.

Other relevant concerns

The truth is that the Church can be influential in a meaningful way without getting intricately involved in politics. “When the CBCP takes a stand on a social justice issue, things really get moving,” says Lisandro Claudio, a political science professor at Ateneo de Manila.

Bishops and priests are – and have long been – active in campaigns against corruption, political dynasties, illegal gambling, mining and environmental destruction. They have been effective advocates of social justice, promoting issues such as poverty eradication, human rights, agrarian reform and peace building in a country riven by violent armed groups.

In the eyes of political scientist Claudio, Bishop Broderick Pabillo is a good example for “what is good and bad in the Church.” Pabillo played a key role in land-redistribution in favour of poor farmers, but he is also one of the most fervent opponents of RH. He once said a typhoon which killed hundreds was a “message” from God. “Bishop Pabillo,” notes Claudio, “is one of those who’d rather vote for a politician who is dishonest than an honest RH advocate.”

The Church is already feeling a backlash: pro-RH groups are questioning the traditional role the Church plays as an election watchdog. The critics ask how the Parish Pastoral Council for Responsible Voting (PPCRV) can be trusted to be impartial when its board members include CBCP members.

Catholic hardliners have more reason to worry about the fact that the majority of Filipino Catholics do not share their view on the RH issue. Most Filipinos are happy being Catholic, but don’t think this means they have to follow every order from CBCP. Some fervent Catholics deride this common attitude as “cafeteria Catholicism”, where followers only pick the tenets they like. They do not seem to appreciate that, in a democratic society, the clergy does not define the law. That is the job of elected legislators.

Social scholar Claudio predicts the Filipino Church will have its hands full dealing with new “enemies” in the future. He says the emergence of social movements who insist on a secular state is “a new phenomenon”. In fact, Southeast Asia’s first ever atheist and agnostic convention was held in Manila last year. Church attendance seems to be going down.

According to Michael Tan, a medical anthropologist, the mass-attendance figures suggest that “we are moving towards becoming a nation of cultural Catholics.” In his eyes, Catholicism is “evolving into a cultural identity rather than a religious affiliation in the sense of agreement with doctrines and practices.” A survey by the polling institute Social Weather Stations recently found out that one out of 11 Filipino Catholics is thinking of leaving the Church.

This may suit some Catholics who are in favour of a “smaller and purer” Church, composed only of true believers. But this seems far from what the CBCP wants. As early as 1992, Bishop Teodoro Bacani predicted that church involvement in state affairs was set to increase: “The Church in the Philippines will not rest content until the whole Filipino nation becomes a disciple of Christ even in its political activity.” His words sounded like those of a fundamentalist ayatollah. The Church’s recent political manoeuvring fits them well, but does not seem to resonate with the people.

Alan C. Robles is a Manila-based journalist and foreign correspondent. He has lectured on online journalism and publishing at GIZ’s International Institute for Journalism.

alanrobles@gmail.com