Coronavirus

Uganda’s poverty rate has risen 10 percentage points

In the first half of 2021, Uganda’s Finance Ministry reported that 28 % of Ugandans were poor. That rate had increased from 18 % before the pandemic. In line with World Bank practice, the official poverty line is the equivalent of $ 1.90 purchasing power per day and head. The Finance Ministry also noted that two thirds of Ugandans had lost at least some income due to the Covid-19 crisis.

It was obvious that things would be challenging. In June 2020, the Uganda office of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) prepared a report on what impacts the novel virus was likely to have. It expected some 4.4 million workers in Uganda’s informal sector to fall into extreme poverty. Women, people with disabilities and chronic conditions, youth and the elderly were said to be most at risk. The UNDP report also predicted that tourism, manufacturing and services sectors would be disproportionately affected.

Statistics are not totally reliable anywhere, but they tend to be especially poor in least-developed countries with weak capacities. It is hard to tell to what extent the UNDP predictions have come true. What the mass media report, however, suggests that things are playing out as foretold.

From the turn of the millennium to the onset of Covid-19, economic growth was generally strong in sub-Saharan countries. Uganda’s gross domestic product increased from $ 6 billion in 2000 to $ 36 billion in 2019 according to the World Bank. However, the population grew from 23 million to 44 million in the same time span, and not everyone benefited equally from growth. As in many countries, a small elite has prospered in particular, and many people say that a small set of government officials has benefited from corruption.

Even before the pandemic, Oxfam, the international charity, had warned that inequality was worsening in Uganda. A key problem was – and is – the unfair distribution of land. While women constitute 73 % of Uganda’s agricultural workforce, for example, they own only seven percent of the land. There are regional disparities too. Oxfam reckoned, for example, that 80 % of rural households were vulnerable to poverty even before Covid-19, compared to less than 30 % in urban areas. It is generally acknowledged that Uganda’s north is much poorer than the south.

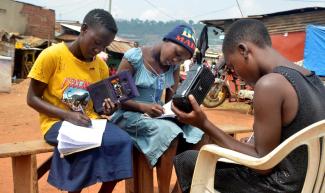

The pandemic has affected access to education. Learners were sent home. Only those with access to digital technology could attend online classes. Regional and gender disparities, of course, play a role in who can and who cannot make use of the internet (see Ipsita Sapra in the Magazine section of D+C/E+Z 2021/10). Radio lessons, however, are less effective.

The government offered cash transfers and food parcels to the urban poor, but these short-term efforts did not help people in rural areas. To afford the efforts, the government had to incur more debt.

The government has promised to change its spending patterns and channel more funds to village committees. Results are yet to be seen. On the other hand, it has announced measures to boost government revenues, and a large share of taxation is levied on consumer spending, which hurts poor consumers in particular.

What is happening in Uganda reflects global trends. The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted global inequality with data showing a widening gap between the rich and poor. While the world’s richest people amassed more wealth, many have fallen into extreme poverty. The worst impacts are felt by people in low-income countries who cannot rely on strong social-protection systems – and where vaccination campaigns have not made much progress accordingly.

Link

UNDP, 2020: Leaving no one behind: From the Covid-19 response to recovery and resilience building. Analysis of the socioeconomic impact of Covid-19 in Uganda.

https://www.ug.undp.org/content/uganda/en/home/library/un-socioeconomic-impact-report-of-covid-19-in-uganda.html

Ronald Ssegujja Ssekandi studies development management at Ruhr University Bochum. The masters’ programme is part of AGEP, the German Association of Post-Graduate Programmes with Special Relevance to Developing Countries.

sekandiron@gmail.com