Egypt

Still aspiring to change the world

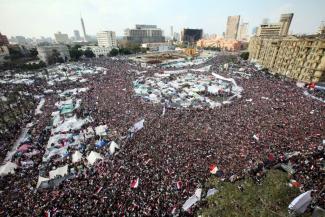

In 2011, Egypt’s youth embodied hope. Young people protested in the streets and ultimately toppled Hosni Mubarak, the president who had autocratically run the country for three decades. The young generation was considered “the main player” in this largely non-violent revolution. Activists expected democracy to improve people’s economic prospects and make under- and unemployment a thing of the past. On 28 February 2011 the cover story of Time magazine celebrated “The generation changing the world”. In Egypt, Al-Ahram, the government newspaper, published a translation of the cover story.

That was then. Today, a sense of gloom has replaced euphoria, and the young generation feels marginalised.

After a transitional period, elections were held in Egypt in 2012. Mohamed Morsi, the candidate of the Muslim Brotherhood, became the country’s first elected president. He did not manage to improve the economic situation, however, but seemed focused on entrenching the influence of his political party. He lost power in a military coup one year after taking office in the summer of 2013.

The country’s new president is Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, the general who led the coup and who was later confirmed in office in elections that were neither free nor fair because the Muslim Brotherhood was banned. In the previous elections, it had proved to be the strongest political force in the country, but the military leaders consider it a terrorist organisation. El-Sisi acted oppressively from the start. Today, he is constraining civil liberties more than Mubarak did.

Those who protested in the streets in 2011 neither support the Muslim Brotherhood nor the military. They did not get what they wanted: a liberated society with opportunities for everyone.

El-Sisi would like to get the young generation on his side. In January last year, he said 2016 would be the “year of Egyptian youth” and promised to start various programmes to improve education and economic prospects. The announcement coincided with the launch of the Knowledge Bank, a state-run project to provide free access to educational online resources that normally are only available to those who pay hefty subscription fees.

A few days later, on 25 January, the police arrested young people. It was the fifth anniversary of the first day of protests in 2011.

Last year, el-Sisi also launched the Presidential Leadership Programme (PLP). It is meant to “enable thousands of youth to start their journey to leadership and employment”. According to the official website, participants will be trained in three stages concerning:

- politics and national security,

- public administration and entrepreneurship, and

- social science and governance.

The First National Youth Conference

In October, the President’s Office supervised Egypt’s First National Youth Conference in the tourist resort of Sharm El-Sheikh. Far away from the congested capital Cairo, 3,000 young people gathered for three days and met experts from many disciplines to discuss political, economic and other issues. The event was linked to the PLP.

Across the country, however, many members of the age group largely ignored the event or even refused to take part. Noor Mohamad was invited to go, for example, but did not want to. She says she is “not interested in official youth activities”. She is 23 years old, has a BA in English literature and has been working in the private sector for a year and a half. In her eyes, the government rhetoric on youth leadership is empty given that the education system fails to prepare students for market requirements.

“Taking care of youth is not done by holding conferences,” says Fatima Abdallah, a 26 year old public-sector employee from Alexandria, Egypt’s second biggest city. “Action is what we need, not words.” In her eyes, the conference was a mere propaganda event.

Mariam Abdelaziz, a 23 year old graphic designer living in Cairo, agrees. She says she heard about the youth conference, but didn’t follow the intensive media reports about it. She is not interested in propaganda, but would like to be informed about enforced disappearances. According to Amnesty International, hundreds of citizens have “disappeared”, but the government stays silent on this matter.

Like many others, Mariam Abdelaziz says she would like to leave Egypt: “I am a temporary visitor in my country, the land of no hope.” To her, “the revolution was a wakeup call”, but she admits her interest in politics has “decreased sharply in the past years”. She feels grateful to those who wanted to introduce change, but points out that life is getting harder.

Not all young people who find the current situation unbearable were supporters of the revolution however. Ayshe Hassan, a 21 year old university student, appreciated the sense of stability and security provided by the Mubarak regime. Nonetheless, she is bitter about officialdom’s broken promises. She says that the status quo makes young people suffer because they lack prospects. Too many die “trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea to get to Europe”, she points out.

While many young people do not believe in the government’s good intentions, some support the president. Ahmed Abo Sinah attended the youth conference as a representative of Arab League’s Youth Committee. He praises el-Sisi’s performance in Sharm El-Sheikh: “I have been there for five days witnessing the amazing work.” In his eyes, the discussions concerning laws, protests, social affairs and religious discourse were worthy.

Mostafa Barakat, who helped to organise the event in Sharm El-Sheikh agrees. “We witnessed a real time of pluralism and freedom of speech.” He says that many young critics of the government have not been arrested.

One result of the conference was the government’s promise to release all detained youth who have not received judgments. It was, however, not the first promise of this kind. An opposition campaign immediately asked online: “Where is the youth?” According to Abo Sinah, however, this campaign was not up to date and failed to reflect recent developments. The truth, however, is that many young people are in detention, and there is no trace of most people who “disappeared”.

Six years ago, Time magazine emphasised that young people used the internet and social media to organise and fight for change. Today, advanced communications technology is not very helpful anymore. In November 2015, groups that support the Muslim Brotherhood tried to rally people for protests via social media, but the response was negligible.

As for the economic situation, it has been becoming more difficult too. With the country running out of foreign-exchange reserves, the government was forced to float the national currency in autumn. Otherwise, the International Monetary Fund would not have given it a much needed loan worth $ 12 billion. As a result, the Egyptian pound depreciated fast, making imported goods more expensive. Inflation has reduced people’s purchasing power.

It is impossible to turn back the clock. Young people’s attitude to life has changed. They do not see much scope for political action now, but they do not agree with the way things are going. In particular, many young women have been reassessing their options (see box). In the long run, some hope that their generation may yet change the world. Fatima Abdallah says: “The light at the end of the tunnel is the young people who become open-minded.”

Basma El-Mahdy is a print journalist specialising in human-rights issues. She is from Cairo and currently studying in Denmark. In this contribution, the names of persons who expressed criticism of Egypt’s current government have been changed.

basmaelmahdy@gmail.com