Masculinity

How young South Sudanese men navigate between tradition and modernity

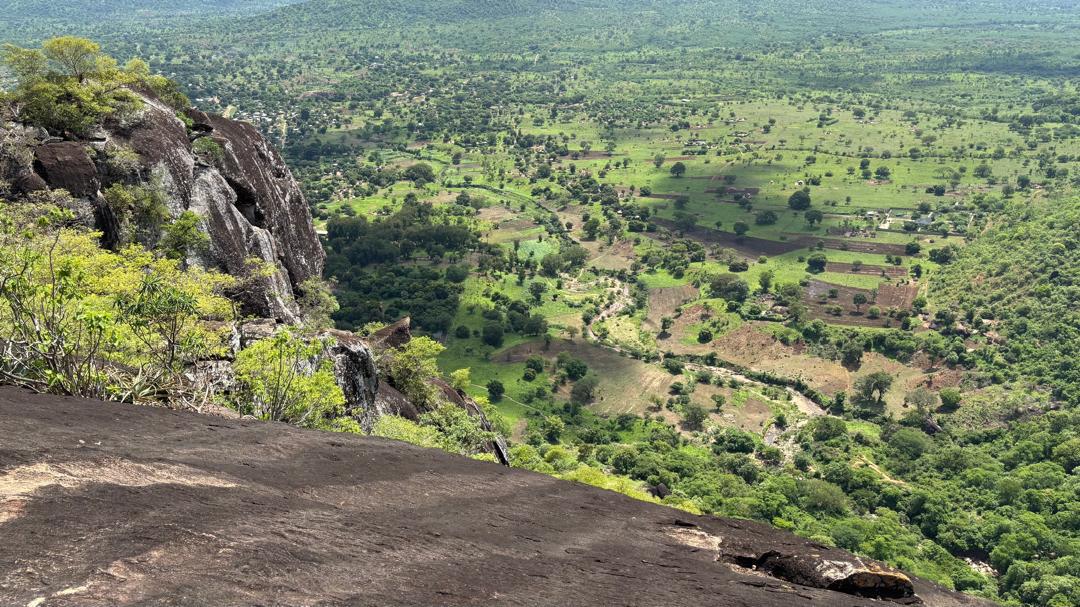

If you want to be taken seriously as a man among the Didinga, you can’t be squeamish. “They smeared us with goat stomach waste,” says Mark Lokulang, recalling the traditional initiation rite for boys aged 15 and older. The homeland of the Didinga ethnic group, whose culture is shaped by livestock farming, lies in the Didinga mountains in South Sudan, in the border triangle with Uganda and Kenya.

Like so many boys before him, the now 16-year-old grew up in a traditional age group classification system that determines what is expected of young males at each stage of their lives. Until the age of 12, boys are considered children who are still inexperienced in various areas of life. The initiation rite described by Mark Lokulang is a crucial step towards becoming a fully-fledged man. It usually lasts three days and takes place away from home in the woods. There, older men teach the adolescents the things expected of a Didinga man: making decisions, herding cattle, protecting their family and showing restraint.

These culturally embedded norms and practices have shaped the identity of Didinga men for generations and determined their place in the community. Mark Lokulang says that even today, the men in his community still tell him that a man must always be strong and brave and show no weakness. If cattle thieves try to steal his herd, he must fight for his cattle and defend his community, not run away.

Mark Lokulang is aware that other teenagers grow up very differently, he knows plenty of people who lead a more modern life in Kenya or Uganda. He himself attends a local secondary school and would like to work in the medical profession one day. For him, being a real man means being a fighter – in the sense not only of a warrior but also of fighting for the things that are important to him in his own life. He wants to use the knowledge he has acquired at school and elsewhere to broaden the traditional idea of what it means to be a “real man”.

Combining tradition and progress

James George also underwent the initiation rite as a young Didinga. He then lived and studied in Kenya before returning to his homeland. Today, the 33-year-old works for the civil-society organisation Root Of Generations, which campaigns for women’s rights. He is the area coordinator for the South Sudanese district of Budi, where the Didinga Mountains are located.

James George points out that many South Sudanese communities continue to be patriarchal. Their gender norms place men at the centre of power and decision-making, while entrusting women with domestic chores, he says.

“Our fathers taught us that a good man owns cattle and protects his family,” he explains. “But today, being a man also means knowing how to create opportunities for oneself and others while resolving conflicts peacefully, taking into consideration the opinions of your sisters, mothers and partners.”

“Muacha mila ni mtuumwa,” says James George, quoting a Swahili proverb that means “One who abandons their traditions is a slave.” For him, masculinity is rooted in history but open to renewal. The challenge, he says, is to grow without losing oneself – and he expresses the hope that future generations will succeed in combining tradition and progress.

A balancing act between two worlds

One person who is attempting to do just that is Daniel Bichiok. He too was born into a traditional value system – that of the Nuer, an ethnic group in which livestock farming also plays an important role. He came from what is now South Sudan to Kenya as a child and now plays professional football in the Premier League, the highest division.

For Daniel Bichiok, his identity as a man is a daily balancing act between two worlds. In his home village, he says, he is expected to lead and provide for his family. In contrast, his modern life in Nairobi requires him to share tasks.

In Kenya, the captain of Nairobi United has learned that being a man is more about the ability to cooperate and adapt than about dominance. Nevertheless, he says, he often feels the pressure of expectations from his South Sudanese family, who consider his lifestyle too Kenyan. However, he does not want to choose one culture and reject the other but rather build a bridge between them – connecting his roots with the opportunity to lead a modern life.

But what is the female perspective on the changing image of masculinity? “In many African societies, a home without a man is seen as incomplete,” says Sunday Lino, a South Sudanese woman who lives and works in Kenya. In her home country, masculinity has always stood for protection and authority, says the 28-year-old. This idea of masculinity once held communities together, but at the same time limited women’s opportunities to take on leadership positions, she says.

“Real masculinity should not suppress,” says Sunday Lino. “It should protect the weak, not control them.” She confirms that ideas about masculinity are currently changing. Now, she says, it is up to the men in South Sudan, Kenya and elsewhere to decide for themselves how they want to express this new masculinity in their lives.

Alba Nakuwa is a freelance journalist from South Sudan. She lives in Nairobi.

albanakwa@gmail.com