Covid-19

African Covid-19 containment strategies have failed

Africa’s coronavirus caseload surpassed the 10 million mark in the second week of January 2022, forcing public health officials to consider a different strategy in response to the disease. As of 12 January 12, the continent had recorded 10.2 million cases, with 232,770 deaths and 9.2 million recoveries, according to the Africa Centre for Disease Control (Africa CDC). South Africa leads the region with 3.5 million cases of coronavirus, followed by Morocco and Ethiopia with one million and 450,000 cases respectively.

With the number of cases still rising, experts say the disease is becoming endemic. The term stands for something that is part of the natural environment, but does not imply that it is harmless. Malaria, for example, is endemic in Africa too.

“We are no longer in the logic of containing the virus,” says John Nkengasong of the Africa CDC. “The virus is everywhere.” A bright light, according to the health expert, is that vaccination helps. While people who got the shots may yet become sick, they are unlikely to be hospitalised. Nkengasong wants calls for more vaccinations and more testing.

Low vaccination rates

Unfortunately, vaccination programmes have not gained much momentum in Africa. Compared with other world regions, immunisation rates are abysmally low. Of almost 8 billion doses administered by mid-January internationally, African countries accounted for a mere three percent, according to the World Health Organizsation (WHO). So far, only about eight percent of the continent’s population were fully vaccinated. High-income countries had rates ranging from 60 % to more than 90 %.

Vaccine supply has improved in Africa however. In January, African health workers had more than 500 million doses of vaccines at their disposal. Experts were urging national governments to show a strong commitment to vaccine deployment. “We’re at a pivotal moment,” said Richard Mihigo of the WHO.

Too close to expiring dates

Many challenges are obvious, including insufficient funding, lack of well-trained staff, inadequate cold-chain logistics and too little digitised data processing. It does not help that prosperous nations have been sending surplus doses close to the expiring dates. Late last year, a joint statement by two important institutions stated that most of the donated pharmaceuticals had a short shelf-life. It was issued by the African Vaccine Acquisition Trust, an AU agency, and the WHO programme COVAX. The acronym stands for Covid-19 Vaccines Global Access.

Indeed, African governments repeatedly had to destroy expired vaccines. Malawi made such an announcement in April 2021 (see Raphael Mwenguwe’s Nowadays on www.dandc.eu). In December, Nigeria’s disposed of more than one million expired AstraZeneca doses. In January, Uganda’s health ministry declared that 400,000 doses, mostly Moderna, had become useless.

Adhere Cavince, a Kenyan intellectual who specialises in international relations, says that donating expired vaccines to Africa runs counter to the donor governments’ rhetoric of solidarity in the pandemic. In his view, the only way to ensure Africa has adequate access to vaccines is to encourage local production (see Mirza Alas on www.dandc.eu).

On the upside, Covid-19 death rates in African countries have stayed below what other world regions have experienced. So far, scientists do not have a full understanding of the reasons. Most likely, it matters that Africans’ average age is low, that the continent’s climate is hot and many people live in rural areas that are not densely populated. Moreover, Africans are believed to have stuck to hygiene rules. On the other hand, underfunded and understaffed health-care systems have probably failed to diagnose and register all coronavirus infections, especially in remote areas.

High economic price

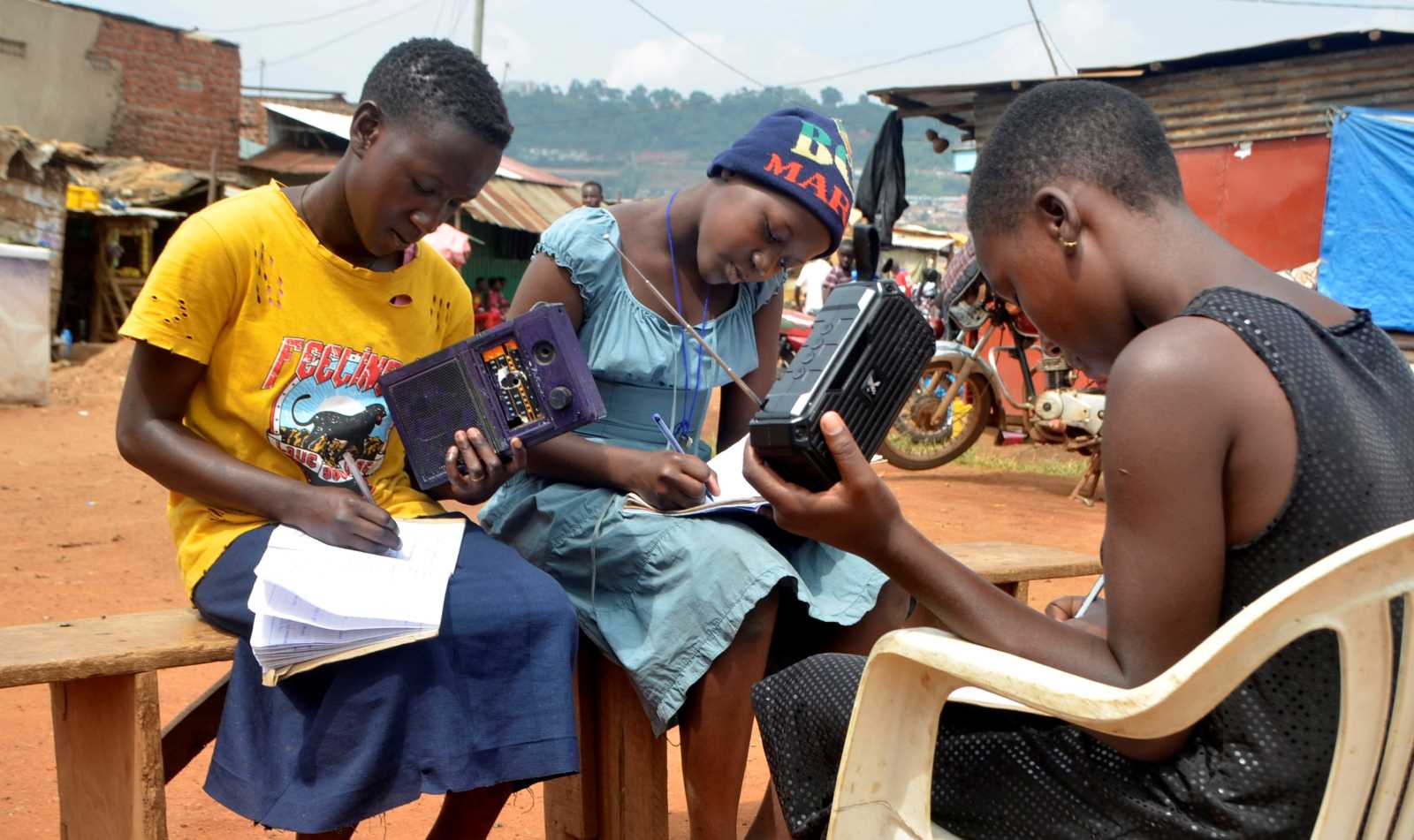

Early lockdown programmes have probably helped too, but the economic price was high. According to the World Bank, Africa’s economy contracted by 3.3 % in 2020, after 2.4 % growth in 2019. The continent has thus been plunged into its first recession in 25 years. Poverty and inequality have worsened (for the example of in Uganda, see Ronald Ssegujja Ssekandi on www.dandc.eu).

The disruption of the global economy, travel bans and snags in international supply chains have hurt. In 2020, exports and imports across Africa are estimated to have fallen a third below the levels of 2019, the year before the pandemic reached the continent . The International Air Transport Association reckons that, due to Covid-19, African airlines had lost over $ 4 billion in revenue by March 2020.

The Omicron variant was discovered in South Africa in the third quarter of 2021. It fuelled the fourth wave of Covid-19. According to the WHO, a six-week surge of infections in Africa has now largely flattened, although case numbers are still high in North and West Africa. Hospitialisation and death rates have luckily remained low.

Matishidisoo Moeti, the WHO’s regional director for Africa, says the fourth wave was brief, but steep and destabilising none the less. “The next wave might not be so forgiving,” she warns. In her eyes, the crucial pandemic countermeasure is vaccination, so programmes must pick up speed.

Ben Ezeamalu is a senior reporter who works for Premium Times in Lagos.

ben.ezeamalu@gmail.com

Twitter: @callmebenfigo