Head of state

The ambivalent role of India’s president

Droupadi Murmu became president in 2022 as the candidate of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). She had previously served as state legislator and state minister in Odisha as well as governor of Jharkhand. In India, governors are representatives of the central government. They monitor state affairs, but normally do not wield executive power. Murmu belongs to the Santals, an Adivasi tribe whose people live in Eastern India as well as in Bangladesh and Nepal. That she became head of state in a country that is marked by caste hierarchies and racial stigmas was a proud moment for Adivasis who have historically been marginalised. Her role is largely ceremonial, since the president does not wield much power in India. Nonetheless, it is a sign of inclusiveness that a Santal woman has risen to it.

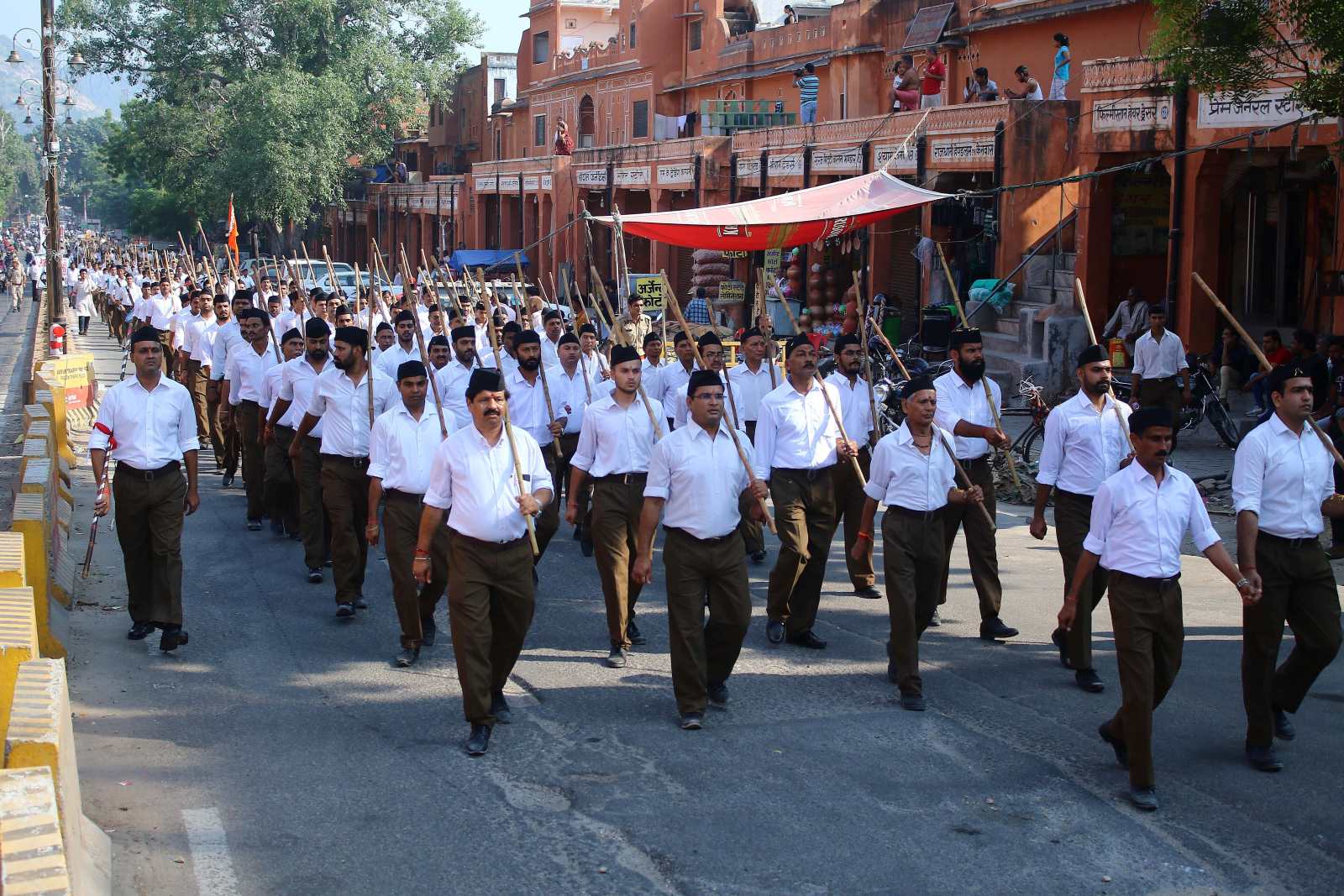

However, there is a divisive aspect to her presidency too. Murmu owes her political career to her membership of the BJP, which claims that India is a Hindu nation. The BJP belongs to a network of Hindu nationalist organisations which is called the Sangh Parivar. According to its ideology, all people residing in India have roots in Hinduism, though, in the course of history, some converted to other faiths. The Sangh Parivar promotes the idea of ghar wapsi, which means “returning home” and is about everyone in India accepting their supposed Hindu heritage.

In recent years, the BJP has stepped up efforts to convince Adivasis that they are in fact Hindus. This claim is anything but obvious. Adivasi communities have historically lived outside mainstream society in rural and forest areas in villages of their own. They speak distinct languages and have long suffered discrimination similar to Hinduism’s lowest castes, the Dalits. Typically, Adivasi tribes have cosmological myths that have been passed on from generation to generation. On the other hand, many Adivasis have joined religions that are based on holy scriptures, including not only Hinduism, but Christianity as well.

Showcasing the Hindu faith

Murmu proudly showcases her Hindu faith. She says she is a devout vegetarian, for example. She belongs to the Brahma Kumaris, a spiritual group that was established in the 1930s and is especially popular among women. She did not inherit her faith as members of Hindu castes do.

The president often reiterates her commitment to Savarna Hindu orthodoxy, which includes the caste order of mainstream Indian society. She is sometimes seen sweeping a Shiva temple at the crack of dawn in the Mayurbhanj District of Odisha. She has attended religious events at the controversial Ram Temple in Ayodhya, which was inaugurated three decades after the demolition of the Babri Masjid mosque by Hindu extremists.

Murmu supports the official line of BJP on issues like Hindi as the national language. This seems awkward as Adivasi languages are typically not related to Hindi.

Though the constitution defines India as a secular nation, Murmu likes to practice her religion ostentatiously. Pictures taken of her during Hindu rituals are used to spread the message that Adivasis are actually Hindus since the president is one herself. That message disregards the multitude of Adivasi cultures.

In various socio-economic conflicts, moreover, Adivasi groups are still being marginalised. Many major mining and infrastructure projects affect their livelihoods in remote areas. Again and again, entire villages are displaced. When Murmu was chosen to be the BJP’s presidential candidate, people hoped she would play a role in supporting Adivasi communities. Those hopes have not come true.

Droupadi Murmu’s role as president is thus ambiguous. On the one hand, she represents the entire nation and is the first Adivasi to do so. On the other hand, she has adopted a Hindu identity, which does not reflect the multitude of Adivasi cultures.

Arun P. Ghosh is a pseudonym. The author of this contribution is an India-based journalist who is in touch with us.

euz.editor@dandc.eu