Right-wing extremism

Global oligarchy, shrouded in secrecy

This comparatively brief essay of about 200 pages elaborates how tax havens have enabled a small global elite of super rich people to shroud their business activities in secrecy. Harrington, a professor of sociology at Dartmouth College, spells out clearly that they avoid much more than only national revenue services. Indeed, offshore financial centres basically allow prosperous persons to escape the laws and legal systems of other nation states. The resulting illicit financial flows do not only harm developing countries, but long-established, prosperous democracies too.

Prosperous people rely on trust funds and letter-box firms in offshore financial centres for their business activities. Such shell companies are beyond the reach of prosecutors and judges from other sovereign states. In a strict literal sense, Harrington elaborates, these centres are not necessarily “foreign” jurisdictions in a legal sense. Due to rather loose financial regulations combined with strict secrecy laws, US states like Delaware or South Dakota or the EU member Luxembourg serve as offshore tax havens too.

The offshore system does not only deprive other governments of essential revenues, it also stifles healthy market competition. The reason is that it allows beneficiaries to grasp harmful and legally dubious business opportunities internationally with only minimal risk. Their shell companies can, for example, invest in mining activities that are destructive in multiple ways, for example because they deplete the environment, breach traditional ownership rights and disregard labour standards. If such a project succeeds, the owners syphon off the profits. If it fails or merely runs into serious trouble, they let the shell company go bankrupt and avoid any personal liability.

No regard for the common good

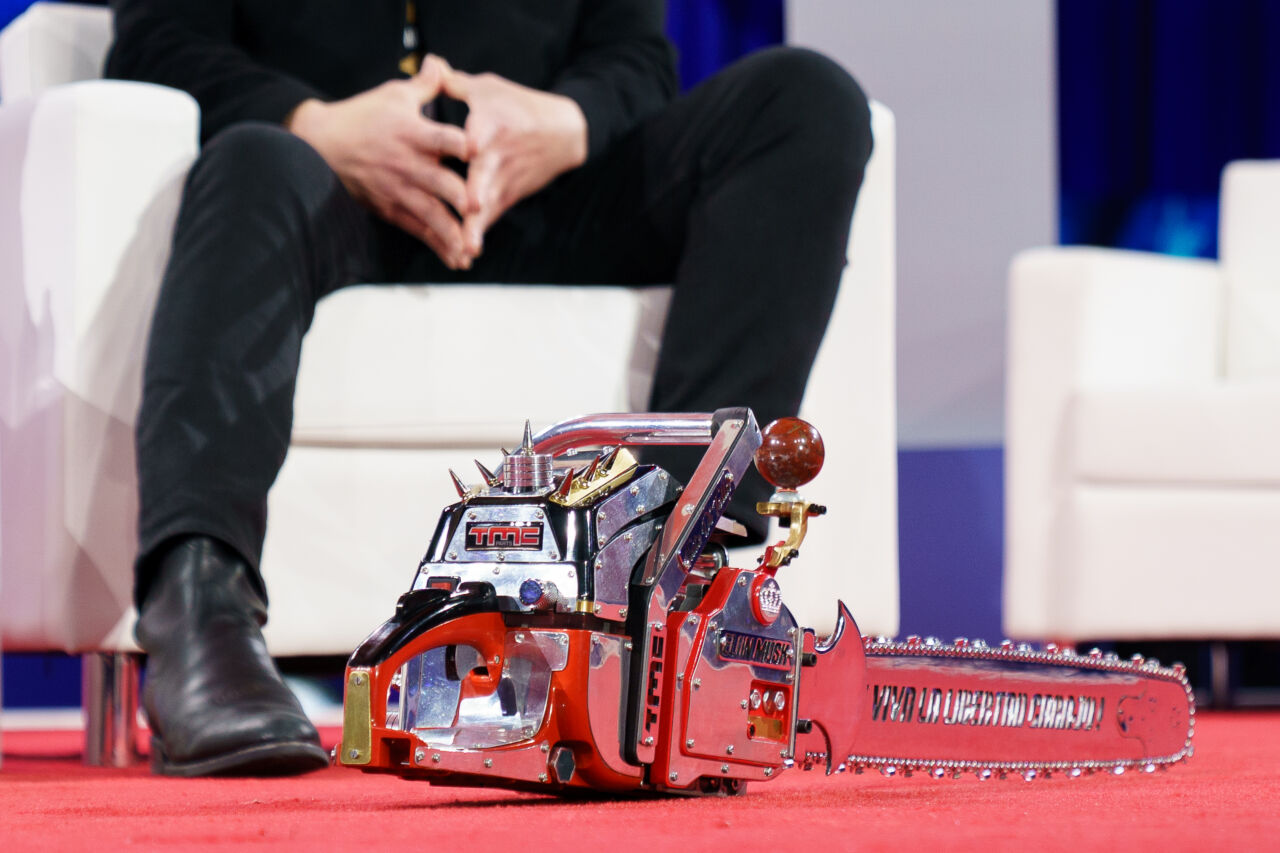

As Harrington argues, this system has given rise to a small set of oligarchs who feel entitled to do whatever they want without regard for the common good. They do not care about environmental protection, labour laws or equal opportunities. According to their libertarian ideology, people must be able to buy whatever they can pay for, and governments breach their freedom should they pass any regulations that limit rich people’s reach. In the scholar’s assessment, they want total liberty for themselves and authoritarian rule for everyone else.

In the eyes of the oligarchs, any questions concerning where they made their money amount to infringements of their personal liberty. This thinking blurs the line between crime and legitimate business activities. Harrington insists that it is no coincidence that tax havens also serve organised crime, including the traffickers of drugs and arms. They all need the secrecy which offshore centres sell. The business model of financial “paradises” is basically to help monied clients break laws of their own countries.

It is no coincidence, the scholar points out, that right-wing forces like Germany’s AfD and Britain’s Brexit campaign typically receive funding from anonymous offshore donors. Right-wing extremists often promise to liberate their nation from global pressures, but they actually limit governments’ ability to regulate and redistribute. They distract attention from the most wealthy people bypassing all sorts of laws and regulation, which is a core reason for worsening inequality. Instead, the extremists agitate against minorities and aggressively deepen divisions between communities.

Mostly anonymous global aristocracy

Harrington likens the global plutocratic elite to the aristocracy of the feudal era. She shares the view that they are above the rules that apply to everyone else. The sociology professor, nonetheless, sees a major difference. The nobility of the past was visible to the public and, to a limited extent, therefore felt obliged to the common good. Today’s plutocrats, by contrast, mostly stay hidden. They see no need to appear legitimate, but assume everyone else owes them gratitude for creating jobs.

In truth, their behaviour is parasitic, Harrington argues. They avoid taxes, so they do not contribute to the hard and soft infrastructure that their businesses depend on. Due to their tax avoidance, middle and lower classes bear those costs. Even in the tax havens themselves, the scholar points out, only a small minority of people actually benefit from the huge financial sector. Typically, these countries are haunted by corruption and crime, and they offer very little scope for upward mobility.

Harrington’s easily readable book elaborates many interesting aspects. They include how Russian oligarchs have become trailblazers, what crucial role the professions of private asset managers are playing and why most of today’s tax havens emerged during the decolonisation of the British empire.

Sustainability versus freedom for the few

Her most alarming message, however, is perhaps that offshore finance has made avoidance of not only tax laws, but rules and regulation in general something of a status symbol. Libertarian ideology suggests that any interference in supposedly free markets is incompatible with freedom as such. This narrative has become deeply entrenched in public discourse. Related rhetoric systematically discredits the role of the state. The full truth is that market efficiency depends on the rule of law, public transparency and regulatory oversight. Market dynamics as such provide none of this.

Sustainability requires capable states – and such states depend on adequate revenues. Illicit financial flows, by contrast, destabilise both nation states and the international community. As Harrington points out, the offshore system provides the basis for an elite insurgence against equality before the law.

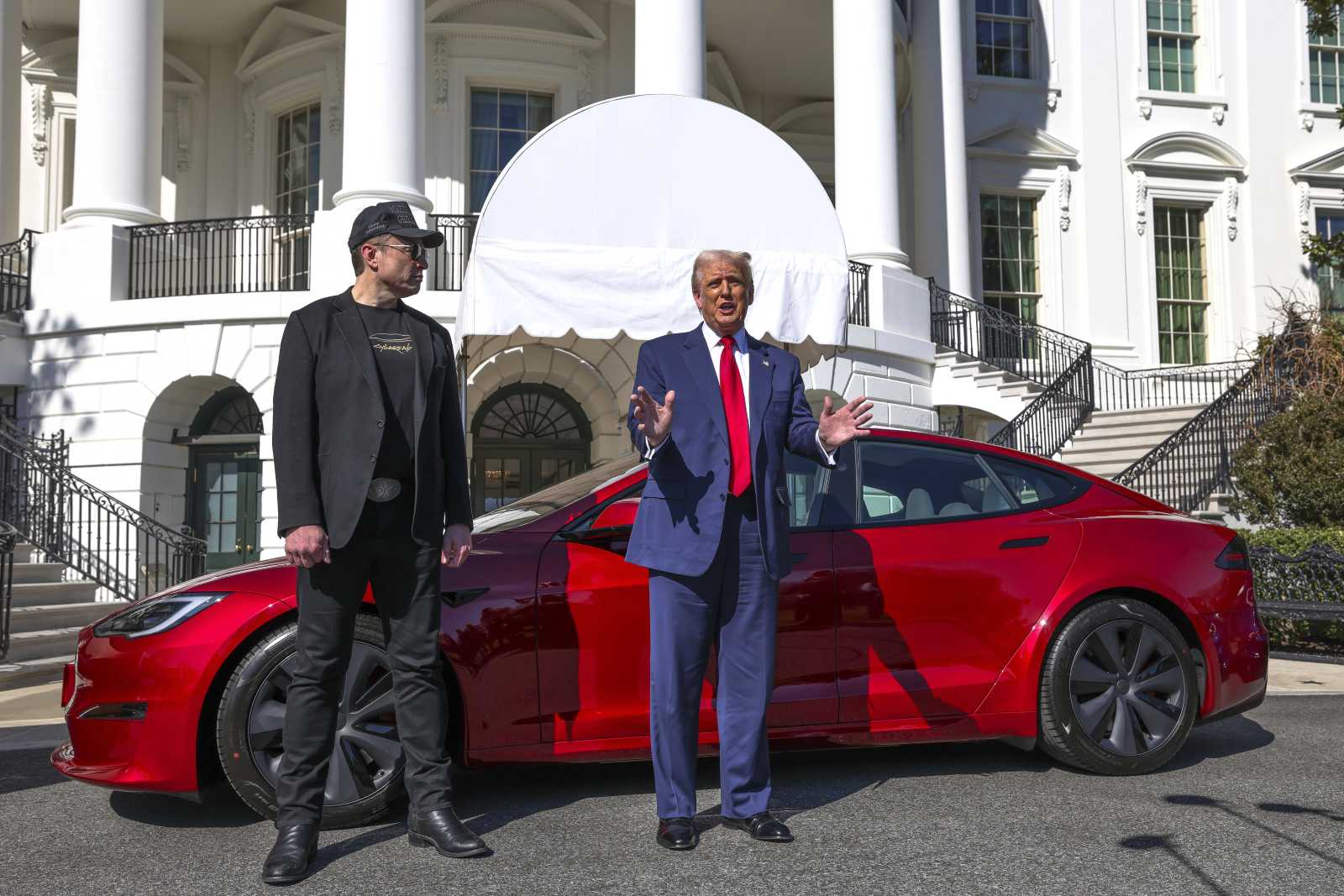

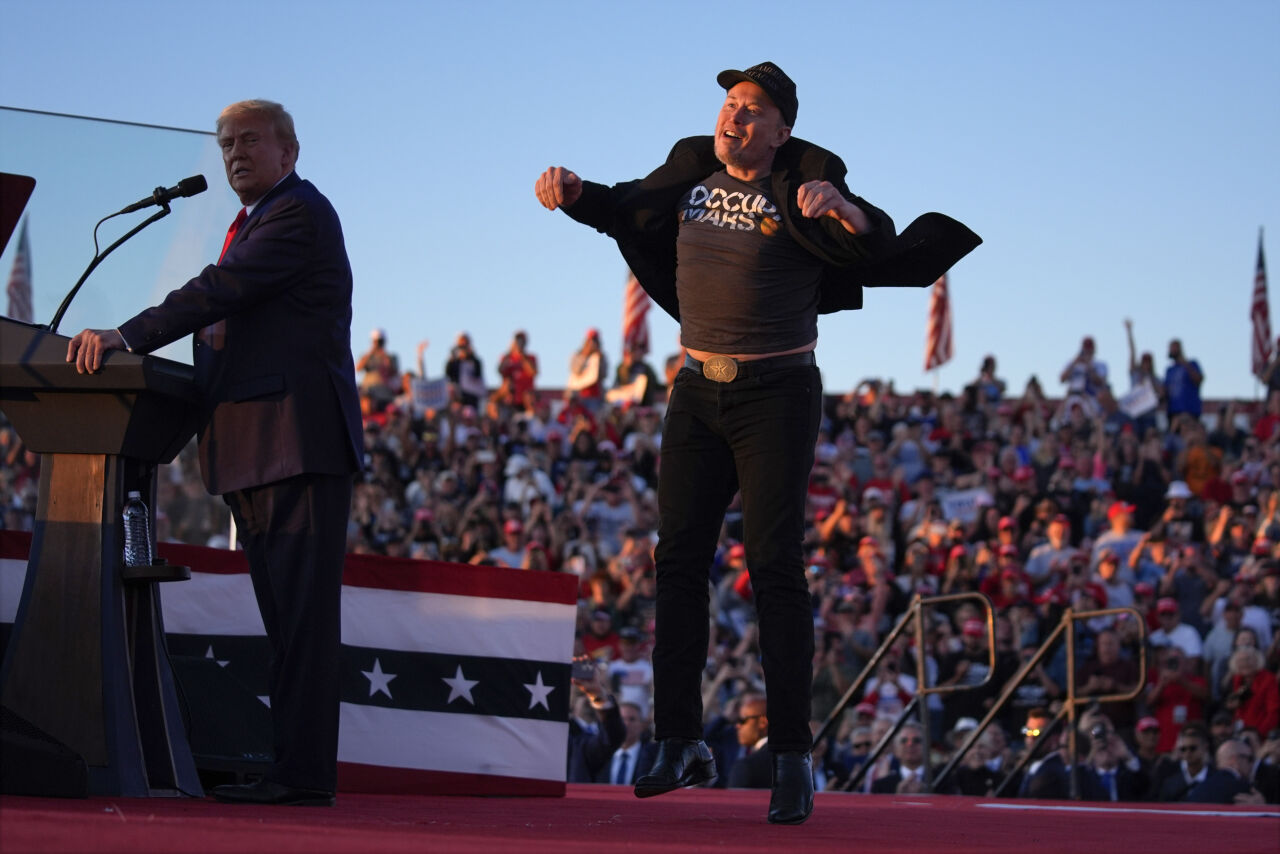

Libertarianism ultimately leads to kleptocratic systems in which the highest bidders buy government services, entrenching their privileges and crowding out any other interests. That is precisely the kind of political system that Donald Trump and his ally Elon Musk are currently trying to build in the USA by dismantling government institutions, undermining the rule of law and attacking the freedom of speech.

Reference

Harrington, B., 2024: Offshore: Stealth wealth and the new colonialism. New York City: W.W. Norton.

Hans Dembowski is the former editor-in-chief of D+C.

euz.editor@dandc.eu