Hate speech

The ecosystem of hate

The “United Nations Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech” defines hate speech as “any kind of communication in speech, writing or behaviour, that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of who they are, in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, descent, gender or other identity factor.”

However, the Indian legal system struggles to strike a balance between hate speech and freedom of expression. For example, the 267th report of the Law Commission of India states: “Hate speech is an expression which is likely to cause distress or offend other individuals on the basis of their association with a particular group or incite hostility towards them. There is no general legal definition of hate speech, perhaps for the apprehension that setting a standard for determining unwarranted speech may lead to suppression of this liberty.” As a result, India’s legal institutions do not sufficiently prevent the spread of hate speech and make criminal prosecution difficult.

In consequence, hate speech is spreading at the highest levels in India. Here are some examples of campaign speeches by Prime Minister (PM) Narendra Modi and other senior BJP leaders:

- During a speech in Barabanki, Uttar Pradesh, in May last year, Modi made false claims about the political opposition and suggested that it intended to damage the newly opened Ram temple, which had been controversially built on the site of a demolished historic mosque in Ayodhya. He stated that if the opposition alliance came to power, it would “send Lord Ram back to the tent and bulldoze the temple.”

- Yogi Adityanath, Chief Minister (CM) of Uttar Pradesh, used the slogan “Batenge toh kitenge” (roughly translated as “If we divide, we will be cut up/destroyed”) several times in 2024. He invoked this slogan particularly in the context of calls for Hindu unity, which BJP representatives believe is being undermined by Muslim minorities, for example. It was also used in connection with attacks on Hindus in Bangladesh and warnings of internal divisions in India. The opposition accused Adityanath of contributing himself to division and inciting hatred against minorities.

- Home Minister (HM) Amit Shah said at an election rally in Jharkhand: “Infiltrators are grabbing land by marrying our daughters. We will bring legislation to prevent the transfer of land to infiltrators if they marry tribal women.” The term “infiltrator” refers to Muslims.

According to the 2024 report by the Washington-based India Hate Lab (IHL), the men in the examples were the three individuals who delivered the most hate speech: the CM of Uttar Pradesh, Adityanath (86 incidents), PM Modi (67 incidents) and HM Shah (58 incidents).

According to the IHL, the 2024 parliamentary elections saw a rise in hate speech at campaign events to 74 %, with 1165 cases recorded. 98.5 % of the recorded cases of hate speech were directed against Muslims.

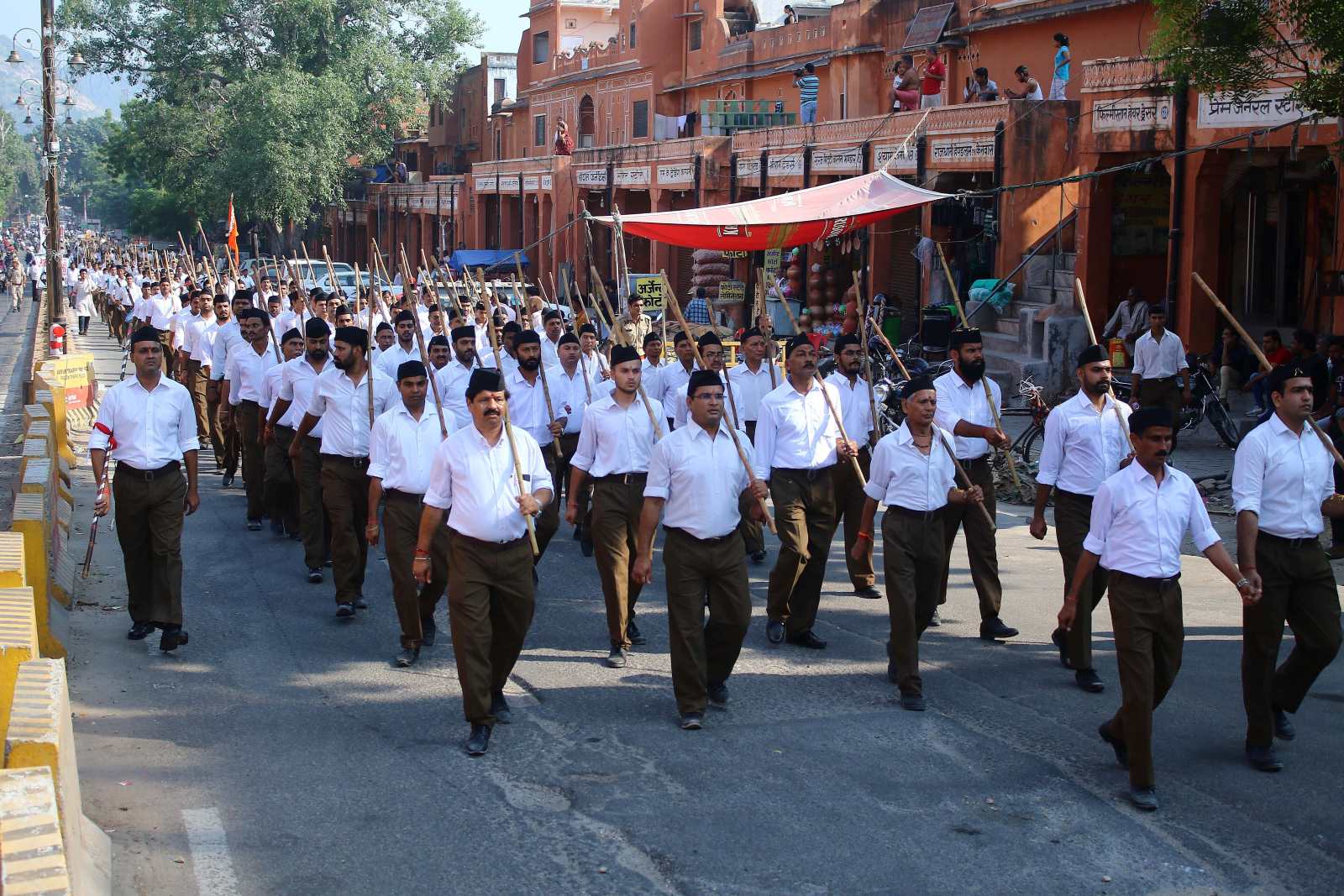

Since 2014, the BJP has won three consecutive elections, and Modi is currently serving his third term as PM. Before becoming the PM, he was the CM of Gujarat, where he was accused of tolerating or even orchestrating the 2002 riots between religious communities, although he was later acquitted of all charges. The BJP’s core ideology is based on Hindutva, the political instrumentalisation of Hinduism to promote Hindu supremacy. The BJP adopted this ideology from its parent organisation, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, a voluntary paramilitary organisation of the Hindu right.

The establishment of a predominantly Hindu nation requires the marginalisation of its minorities. This marginalisation can take various forms, including structural discrimination, violence and hatred. Hate speech is an effective means of demonising minorities. It originates with those in power and gradually becomes entrenched in various systems and strata of society. The primary goal of hate speech is to marginalise and harm the target group and to create a climate of fear and division.

Speech becomes crime

Hate speech contributes significantly to the rise in hate crimes, which are criminal offences motivated by prejudice against a victim’s perceived membership of a particular social group. When influential individuals or organisations spread hate speech, they legitimise prejudice and create an environment in which violence against certain groups is normalised. This can lead to an increase in discriminatory acts, physical assaults, vandalism and even large-scale violence, as has been observed in various cases across India.

Speech that dehumanises or demonises a community can lead to civil unrest, exacerbate tensions and result in the loss of life and property. An ecosystem emerges that protects the perpetrators and punishes those who stand up to them. For example, in 2018, Jayant Sinha, a minister at the time, honoured eight men with a garland of flowers after they were released on bail following their conviction for the lynching of a Muslim man. Furthermore, a 65-year-old activist named Parwez Parvaz, who had filed a lawsuit against CM Adityanath for alleged hate speech that led to riots, was convicted of gang rape. Several media outlets have expressed doubts about the lawfulness of the ruling.

In response to the rising tide of hate speech and hate crimes, several organisations and initiatives have emerged to combat these issues and promote social harmony. Notable efforts include:

- “Hindutva Watch”, an initiative that focuses on documenting and exposing hate speech and violence that takes place under the guise of Hindutva. Its goal is to hold perpetrators accountable and raise awareness of the consequences of such rhetoric.

- The aforementioned IHL, a research and advocacy group that analyses trends in hate speech and its link to hate crimes. The lab provides data-driven insights that inform policy-making and public discourse.

- “Halt the Hate”, a campaign by Amnesty International that aims to track and report incidents of hate crimes in India. The project’s goals are to support victims, advocate for justice and call on authorities to take strong action against hate speech and violence.

Public statements and speeches by political leaders, including PM Modi, were sometimes seen as indirect endorsement or non-condemnation of hate speech, encouraging individuals and groups to express such views more openly. Raqib Hameed Naik, founder of Hindutva Watch and affiliated with IHL, says: “The phenomenon of sectarian hatred is not a recent development in the country. However, it manifested in a more nuanced form. The necessity for a figure to incite societal discord and exacerbate preexisting cleavages has been identified. This has culminated in the marginalisation and subsequent relegation of Indian Muslims to second-class citizens in their own country.”

Suparna Banerjee is an associate fellow at Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF).

mail.suparnabanerjee@gmail.com