Stillbirths

A question of life and death

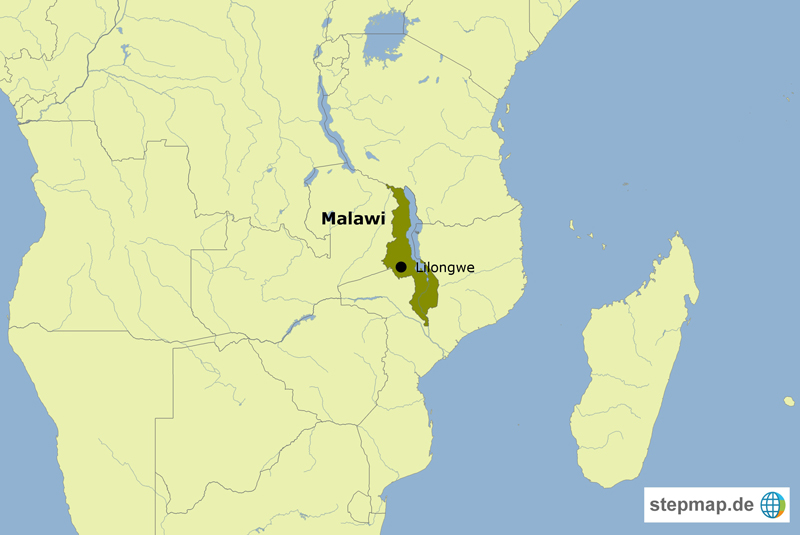

Stillbirths – the death of a baby before or during delivery – are at worrisome levels in Zimbabwe. The country was shaken last July when seven infants were stillborn in a single night in Harare Central Hospital. A staff doctor, Peter Magombeyi, tweeted a photo of the babies wrapped in green cloth, with the message: "We have been robbed of our future, including our unborn babies. Please stop the looting."

Comprehensive statistics on stillbirths in Zimbabwe are elusive, but several academic studies show the extent of the problem. For example, a 2018 study by Solwayo Ngwenya at Mpilo Central Hospital in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe’s second largest city, finds a stillbirth rate there of 30.5 per 1,000 births in 2016.

Shingairai A. Feresu, who had done a study about stillbirths at Harare Maternity Hospital in 2005, estimates a country-wide stillbirth rate of 33 per 1,000 births. According to her, poor prenatal care is to blame for the high rates. “There is a need to improve quality of care and access to emergency care during labour and delivery,” Feresu says.

Zimbabwe is no exception. An October 2020 Unicef study titled “A neglected tragedy: The global burden of stillbirths” reports that worldwide almost 2 million babies are stillborn every year. About 84 % of these cases are in low- and lower-middle-income countries. “A majority of stillbirths could have been prevented with high quality monitoring, proper antenatal care and a skilled birth attendant,” Unicef says.

Yet these services are scarce in Zimbabwe. The country has seen a wave of strikes by doctors and nurses, and its hospitals have persistent shortages of medical materials and equipment. Hospitals and doctors are failing to detect and treat even relatively simple conditions that contribute to stillbirths.

One such condition is maternal high blood pressure. Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension (PIH) is responsible for many stillbirths, says Marylin Chatsi, a midwife at a public hospital in Harare. “PIH is also contributing to mothers dying during those stillbirths.”

The government, meanwhile, is moving to transfer doctors’ and nurses’ employment to the Defense Forces Service Commission, a uniformed forces service agency, to make it more difficult for them to strike again. This will backfire, says Harare-based nurse Millicent Dewure. “We will work, but the attention we give to expecting mothers will be haphazard as long as we know that we won’t be free to show our displeasure through protests or strikes.”

Pregnant women are caught in the administrative crossfire. “I’m in my fourth month of pregnancy and already my fears are growing,” says Nobuhle Dlela, 25, who has had six stillbirths. “It disturbs me a lot.”

Jeffrey Moyo is a journalist in Zimbabwe.

moyojeffrey@gmail.com