Development policy

Religion needs to be a part of the solution

For four out of five people worldwide, religion plays an important role in their lives. In many of Germany’s development partner countries, the figure is even higher. Faith and religion are meaningful for them and provide guidance for their actions. So, regardless of personal views on religion, it should be clear that any value-based development policy that is supposed to take people seriously must also take their world view seriously. And that means that development policy needs to take systematic account of the realities of religious, normative and cultural life in partner countries.

Yet there is massive disregard for the relevance of religion in the foreign and development policy of the present German government. Around ten years ago, the then ministers for foreign affairs and development and economic cooperation, Frank-Walter Steinmeier and Gerd Müller, recognised the strategic importance of religion in international politics. They provided key funding and established international structures. At the same time, Angela Merkel’s government created the office of the Federal Government Commissioner for Freedom of Religion. As a result, Germany assumed a pioneering role on the international stage – a role that is now being jeopardised, even abandoned, through woeful neglect.

This can be seen, for example, looking at the International Partnership on Religion and Sustainable Development (PaRD), a network initiated by Germany in 2016. It plays a crucial role by bringing together over 150 international and religious organisations and a number of governments to share experiences and work together to develop solutions. PaRD is a vitally important instrument for promoting religious competence among representatives of German foreign and development policy and for ensuring a professional approach to religions in general. But despite its successful performance and track record, the international network faces an uncertain future. Under Federal Development Minister Svenja Schulze, funding has been cut. Even worse: the current funding could expire at the beginning of 2025.

Lack of understanding

Failure to appreciate the influence of religious actors is also apparent in the German development ministry’s Africa strategy and feminist development policy strategy. Despite being a major factor, religion receives only marginal consideration in each case.

A development policy that ignores the religious context in partner countries for ideological reasons and pushes its own ideas instead, is perceived by many as a neo-colonial policy. Sustainable development and peaceful coexistence can be achieved only by harnessing diverse societal forces – including religious ones.

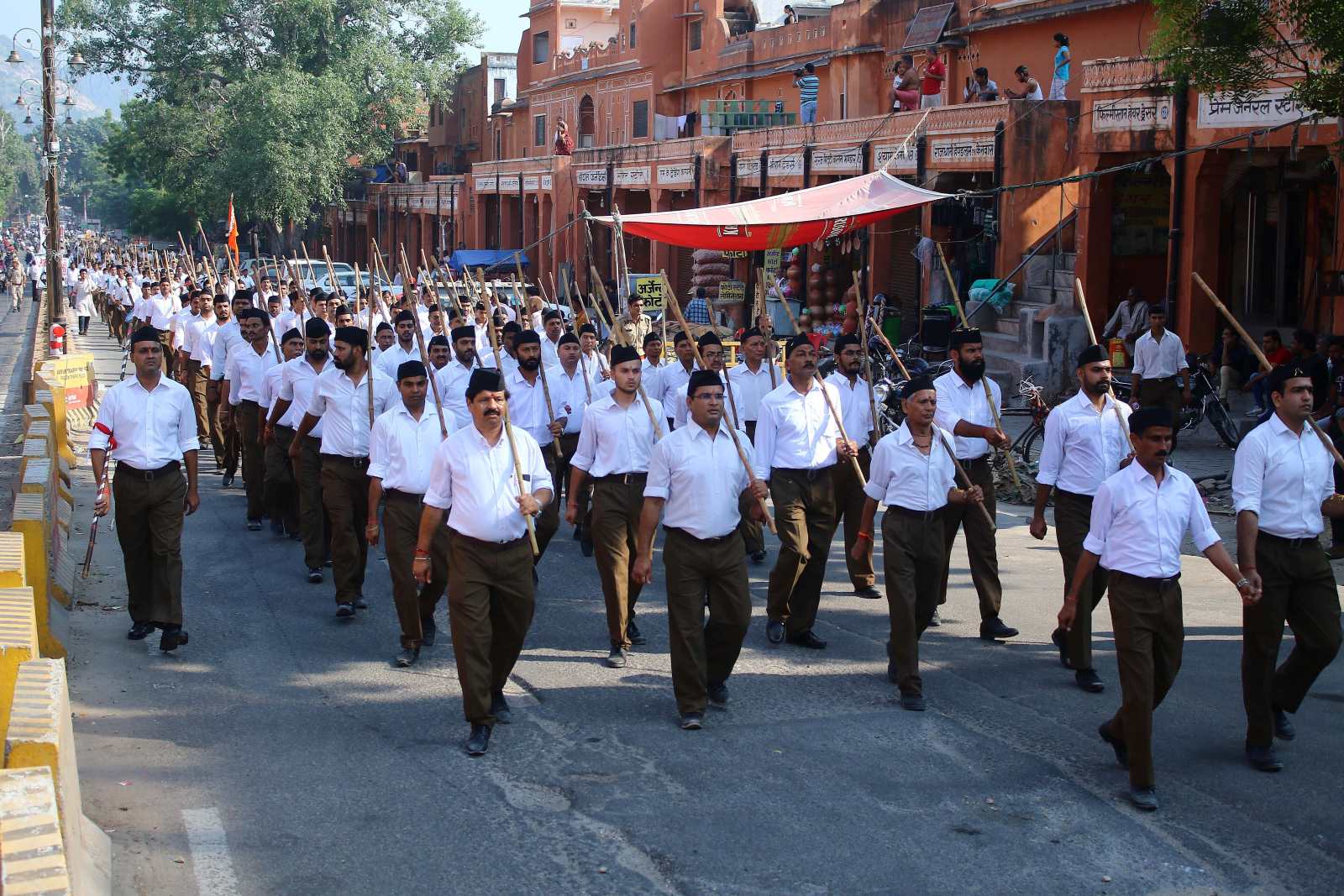

Religious communities have the power to shape society and can therefore contribute to the acceptance, effectiveness and sustainability of development cooperation projects. Many of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as gender equality, climate action and inclusive and equitable education, can only be achieved with the support of religious actors – not without them and certainly not against them.

Religious actors often enjoy much greater trust than government agencies, particularly in the so-called global south. In countries where state development cooperation is limited by war or conflict or where state structures no longer exist, religious actors continue to be active and carry out important work for and with the people affected, even in remote regions.

Ambivalent role

They play a key role in grassroots awareness campaigns. One example of this is the fight against female genital mutilation in Mali. In 2020, a hundred religious authorities there helped to save 400 girls from genital mutilation in just one year.

The UN and the World Bank estimate that, in parts of Africa, religious organisations are responsible for nearly half of all the social, educational and health services delivered. In many countries, a healthcare or education system would be unthinkable without the contribution of religious communities.

At the same time, the ambivalence of religions and religious communities must not be ignored. Religious authorities can unleash or resolve conflicts. Religious communities can be perpetrators as well as victims of discrimination and persecution. Religions are sometimes misused to prevent democratic reform or to secure power. So, where religions are part of the problem, it is important to make them part of the solution.

Particularly in view of the decline in religiosity in Germany and the continuing high level of religiosity worldwide, priorities need to be set to increase religious competence in the foreign and development ministries as well as in governmental implementing organisations and to provide sustainable financial security for established networks such as PaRD. If religious context is not taken into account, the German government’s self-declared feminist development policy will also be doomed to failure.

This may seem strange in secularised Europe, where churches face dwindling memberships and mounting criticism, but development cooperation without a religious component will always remain patchy. Regardless of any ideological bias, the German government should recognise this.

Thomas Rachel is the CDU/CSU parliamentary group’s spokesman on ecclesiastical and religious policy in the German Bundestag. He is also a member of the Bundestag Committee on Economic Cooperation and Development, federal chair of the Evangelical Working Group of the CDU/CSU (EAK) and a member of the Council of the Protestant Church in Germany.

thomas.rachel@bundestag.de