Human rights

Sustainability certifications: stricter criteria needed

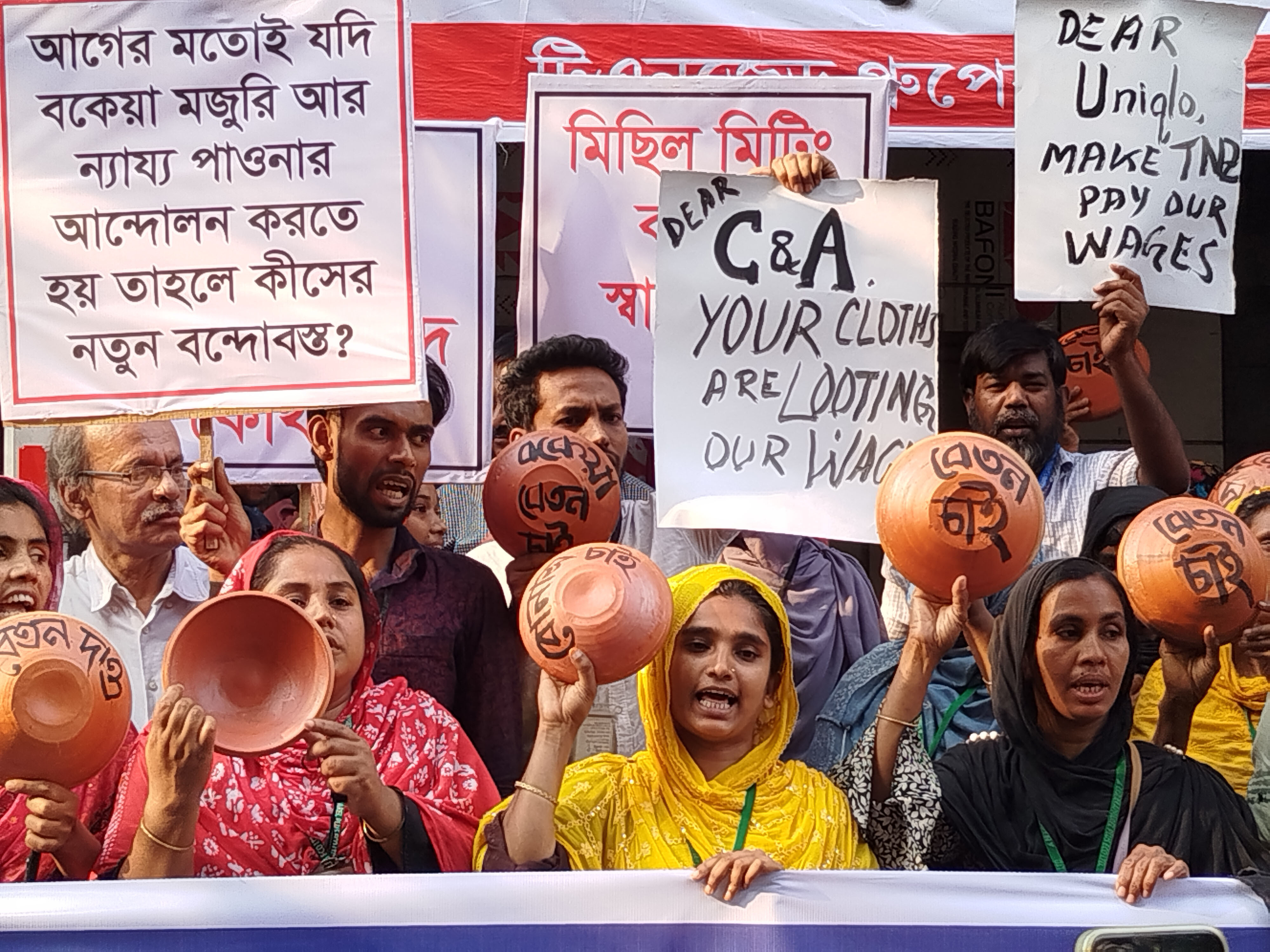

The garments industry has long faced criticism for human-rights violations and harmful impacts on the environment (see Katja Dombrowski at www.dandc.eu on the ecological footprint of the textile industry). In Germany, several initiatives are striving to improve manufacturing conditions internationally. One of them is the Textiles Partnership (see box). Moreover, numerous labels on retail garments are meant to help consumers make choices that are more socially responsible and ecologically sustainable. In September 2019, Germany introduced the first government-run sustainability label for garments. It is called “Grüner Knopf” (“Green Button”) – and is the brainchild of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).

According to the BMZ, 78 companies have been certified in the two years since the label was launched, and around 150 million garments bearing the label were sold. Major customers include the faith-based charities Caritas and Diakonie, which purchase supplies for hospitals and old people’s homes, as well as retail discounters Aldi and Lidl. Moreover, the major railway company Deutsche Bahn has equipped tens of thousands of employees with Green Button clothing. However, major international fashion brands such as C&A, H&M and Zara are not on board so far.

New legislation on supply-chain management

Unlike other certification systems, the Green Button audit does not only assess the textile product in question, but also the company itself as well as the supply chain. This approach makes very good sense.

However, the new supply-chain legislation, which the Bundestag (Germany’s federal parliament) adopted in 2021, will oblige large companies to handle matters more responsibly from 2023 on. It uses similar criteria. Given that voluntary initiatives like the Green Button and the Textiles Partnership only really add value if they significantly exceed legal requirements, the Green Button should toughen up its criteria. The current ones are not rigorous enough.

In particular, Green Button certification still fails to cover the entire manufacturing supply chain. It only takes account of the final processing stages, including cutting, sewing, bleaching and dyeing. It thus neglects the appalling working conditions in spinning mills as well as child labour during the cotton harvest. Moreover, certification so far only requires that employees get a minimum wage, not a living wage. The difference between the two is huge. In most countries, the statutory minimum wage would have to rise by a factor of two or even three to be enough to live on (see Nazma Akter on www.dandc.eu).

Superficial reporting

Certified companies do not do sufficient public reporting moreover, as the civil-society organisations FEMNET and Public Eye revealed in a review of 31 companies’ public disclosures. Most of the companies reported only superficially on risks in their supply chain and failed to identify any tangible action for preventing widespread human-rights violations such as gender-based violence in factories or the repression of trade-union activity.

There is also a need for improvement at the product level. Green Button certification accepts other “credible sustainability labels” such as the Fairtrade label or the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) as proof of compliance with social and environmental criteria. However, certification for those labels is based on audits that private, profit-driven companies conduct in factories. Their audits are unfit to detect all labour-rights violations, such as discrimination against women, for example.

The huge social-audit industry that has emerged in the past two decades has not brought significant improvements so far. It is equally worrisome that some of the certification systems have gaping holes. GOTS, for example, may have some credibility in regard to environmental compliance, but not human rights.

Green Button 2.0

The BMZ has upgraded the approach to “Green Button 2.0”. The final version will be published shortly after the completion of this article. One of the positive changes revealed so far is that companies will need to understand their supply chain better. For example, audits will henceforth consider the origin of fibres and materials too. In addition, companies will have to document gaps between their current wage and the living wages and present a strategy for pay increases. Nonetheless, the Green Button 2.0 criteria are still too soft:

- At the product level, Green Button 2.0 continues to rely on other sustainability labels and thus reinforces their weaknesses.

- Living wages are still not made mandatory, nor is progress on successive pay increases. A mere strategy for increasing wages is all that is required.

- Companies are still not forced to publish their list of suppliers – although many already volunteer this information on their websites.

- Companies are allowed to set their own priorities when assessing supply-chain risks; so they are likely to sidestep critical issues.

The Green Button is advertised as being “socially sound – environmentally sound – government-run – independently certified”. Nonetheless, it neither requires living wages in the supply chain nor guarantees that products are manufactured without gender discrimination or other violations of labour rights. Even the updated version thus fails to guarantee significant supply-chain improvements.

The bottom line is that the Green Button sets the bar too low. To prevent government-certified greenwashing, the bar must be raised. For good reason, the Green Button advisory council has stated: “In cases of doubt, the Green Button 2.0 should prioritise a high level of ambition and deep penetration of the supply chain over attracting as many companies as possible.”

Links

Green Button:

www.gruener-knopf.de/en

Factsheet: Does the “Grüner Knopf” deliver on its promise? FEMNET and Public Eye, 2021:

https://www.publiceye.ch/fileadmin/doc/Mode/2021_PublicEye_Femnet_GruenerKnopf_Factsheet_EN.pdf

The government’s response: BMZ statement on the FEMNET/Public Eye research report:

https://www.gruener-knopf.de/en/press/bmz-statement-report-femnet-and-public-eye

Gisela Burckhardt chairs the board of directors of the civil-society organisation FEMNET, which campaigns for the rights of women in the textile sector.

gisela.burckhardt@femnet.de